Existentialism Definition: Revealed in Sartre's No Exit

No Sortie Pour Sartre.

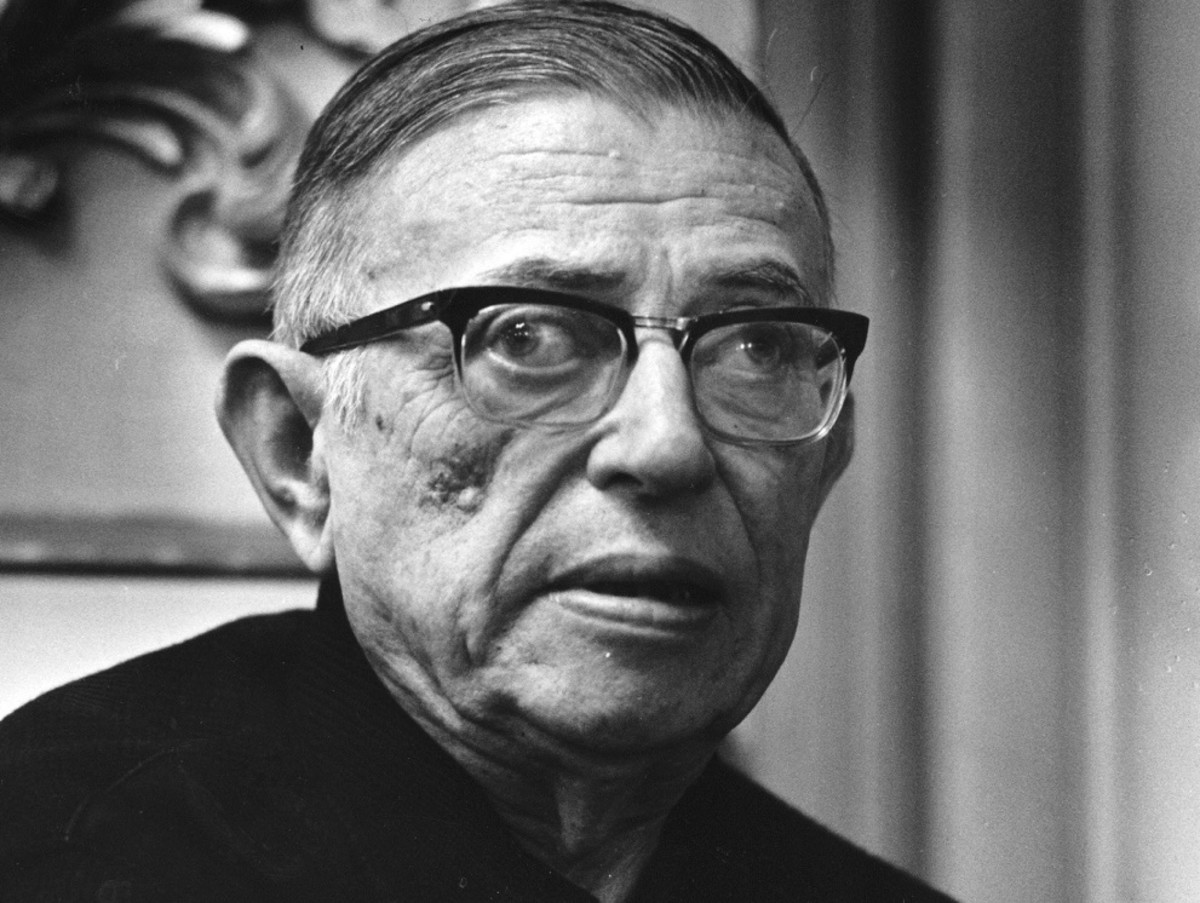

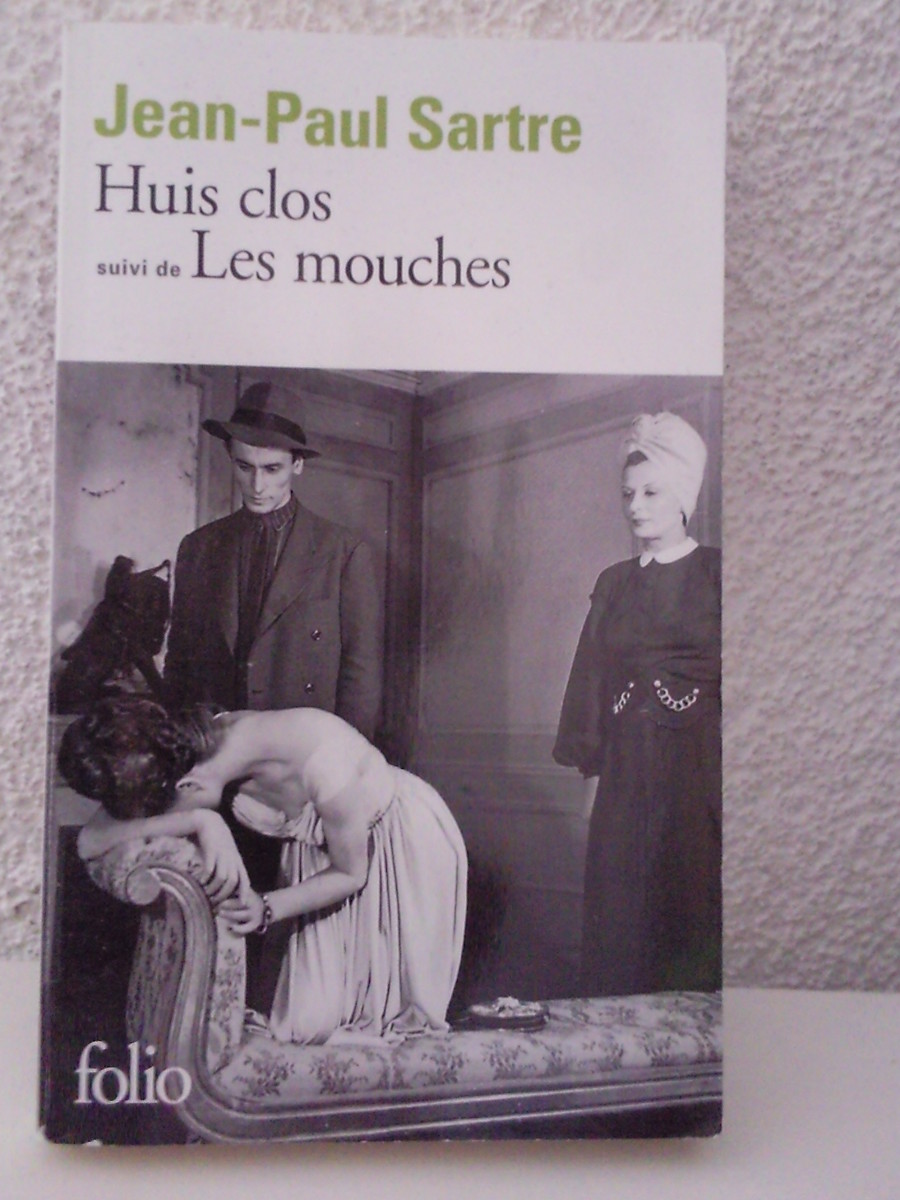

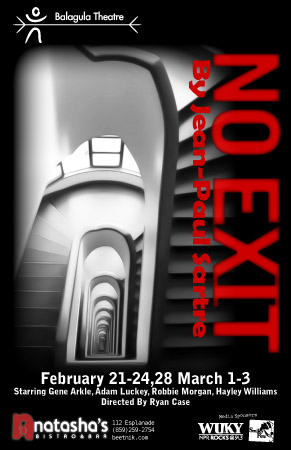

Jean-Paul Sartre’s No Exit, written in the waning years of World War II, is a play which ironically allegorizes the existentialist philosophy, in a one act scene depicting Hell. The effect this iconic work had on the faithless era, made Sartre a paragon of the existentialist school of thought. Brian Wilkie and James Hurt write in Literature of the Western World Volume II, “For many of his contemporaries, even those who knew his work only secondhand, existentialism was the only persuasive faith in a frightening age notably lacking in faith, and Sartre was existentialism’s exemplary figure...” (1870). Being that No Exit is Sartre’s most accomplished work, it then stands to exemplify the whole of existentialism’s epoch, imparting to it, a universal and timeless quality. For not only are philosophically defining works timeless and universal in their own right, but existentialism’s constituents, “God is dead”, “man is alone”, and “life is absurd”, independently comprise a timeless concern of all “thinking” persons in every “thinking” era, and is emphatically explored in the literary dialogue of No Exit’s trinity of the damned, Garcin, Inez, and Estelle.

Through these three characters, Sartre implements each of the three existential constituents. Garcin, the deserter, concludes his final dwelling in a “life is absurd” soliloquy: This bronze. Yes, now’s the moment; I’m looking at this thing on the mantelpiece, and I understand that I’m in hell. I tell you, everything’s been thought out beforehand. They knew I’d stand at the fireplace stroking this thing of bronze, with all those eyes intent on me. Devouring me. What? Only two of you? I thought there were more; many more. So this is hell. I’d never have believed it. (1899)

Inez, the gynocentric concludes, “Dead! Dead! Dead! Knives, poison, ropes--all useless. It has happened already, do you understand? Once and for all. So here we are, forever” (1899), in a “God is dead” rhetoric. And as the “baby-killer” Estelle points out, in finding she will be living without a reflection, “When I can’t see myself I begin to wonder if I really and truly exist. I pat myself just to make sure, but it doesn’t help much” (1883). Through this observation, she illustrates the “man is alone” element.

References:

In regard to existentialism’s “God is dead” element, there is a peculiarity in Sartre’s choice for No Exit’s setting. For acknowledging Hell entails an acknowledgement of Heaven, which in turn presupposes God’s existence. So why risk a living God in an existential play? Its ironical effect. Sartre’s characters, well aware of their locale, display “Christian” expectations concerning their damnation. One of Garcin’s first questions to Valet is, “But, I say, where are the instruments of torture?” (Sartre 1873). Inez herself mistakes Garcin for a torturer, and Estelle thinks she’s to sit with her faceless husband (Garcin) for eternity. It is only after Garcin declares, “Hell is--other people!” (1899), that the reader identifies Hell as not the literal “underworld”, but as Sartre writes, “I mean that if relations with someone else are twisted, vitiated, then that other person can only be hell” (1872). Which, coupled with Sartre’s following statement declaring that, “other people are the most important means we have in ourselves...” (1871), and not in fact God, keeps YHWH buried; and keeps existentialism consistent with its alternative literary view to one of the most universally debated topic known to “thinking” man.

Great literature is “thinking” entertainment. It provokes the human conscious to consider the intrinsic views of its author, and offers new perspectives on highly debatable topics, such as the existence of God, the absurdity of life, and the desolation of mankind. Existentialism, which resolves all three of these issues within its ideology, then makes for a promising foundation to great literary efforts. This foundation, combined with the entertaining voyeurism that is observing an existential awakening in Hell, is what makes Jean-Paul Sartre’s No Exit timeless and universal.