Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s "A Psalm of Life"

Introduction and Text of "A Psalm of Life"

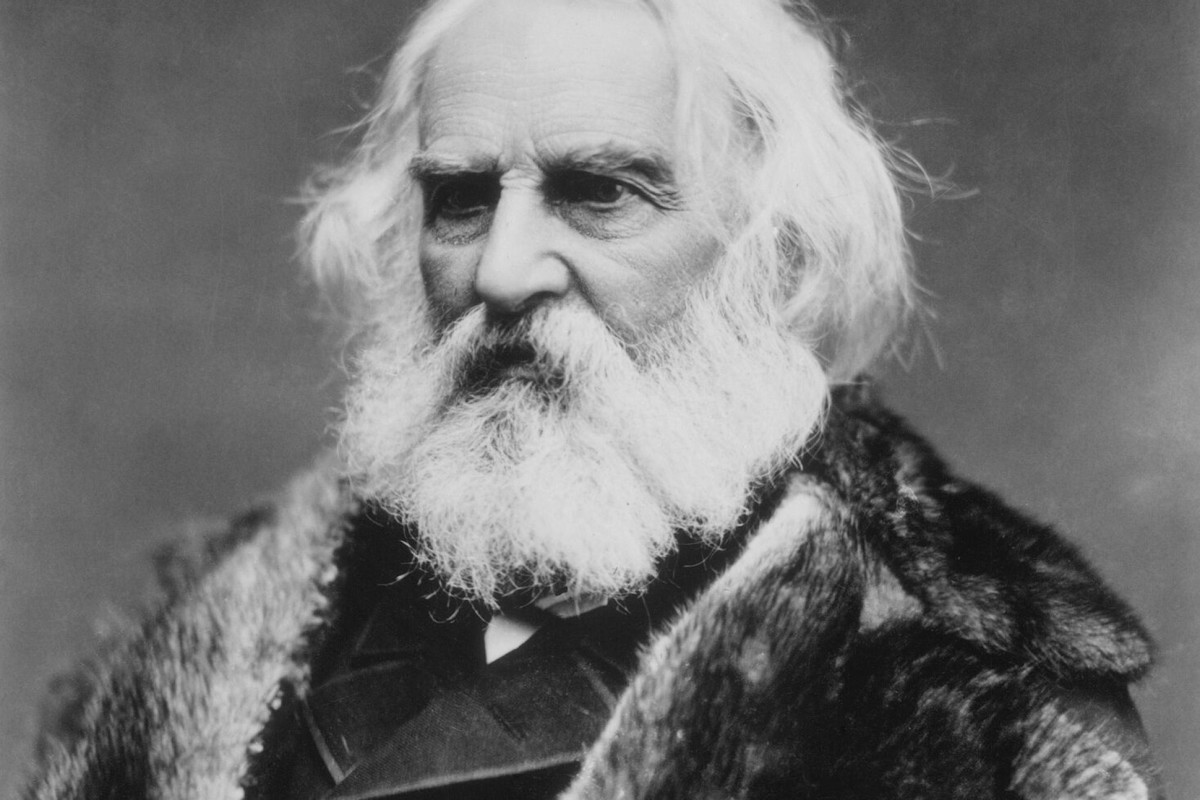

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's poetry was enormously popular and influential in his own lifetime. Today, most readers have heard his quotations so often that they have become "part of the culture."

For example, many readers will recognize the line, "Into each life some rain must fall," and they will find that line in his poem called "The Rainy Day." No doubt it is this Longfellow poem that helped spread the use of "rain" as a metaphor for the melancholy times in our lives.

Longfellow was a careful scholar, and his poems reflect an intuition that allowed him to see into the heart and soul of his subject.

Critic and editor J. D. McClatchy says that Longfellow was "fluent in many languages," and the poet translated such works as Dante's The Divine Comedy.

Other Longfellow translations include "The Good Shepherd" by Lope de Vega, "Santa Teresa's Book-Mark" by Saint Teresa of Ávila, "The Sea Hath Its Pearls" by Heinrich Heine, and several selections by Michelangelo [1].

The poet also achieved fame as a novelist with his novel Kavanaugh: A Tale. This work was touted by Ralph Waldo Emerson for its contribution to the development of the American novel.

Longfellow also excelled as an essayist with such works as "The Literary Spirit of Our Country," "Table Talk," and "Address on the Death of Washington Irving."

The poet’s highly spiritual poem "A Psalm of Life" offers a wise piece of advice regarding the issue of facing life with a proper positive attitude. The alternative is to allow life to defeat one's spirit which leads to failure and lack of achievement.

Longfellow has said that the poem is "a transcript of my thoughts and feelings at the time I wrote, and of the conviction therein expressed, that Life is something more than an idle dream" [2].

A Psalm of Life

What The Heart Of The Young Man Said To The Psalmist.

Tell me not, in mournful numbers,

Life is but an empty dream!

For the soul is dead that slumbers,

And things are not what they seem.

Life is real! Life is earnest!

And the grave is not its goal;

Dust thou art, to dust returnest,

Was not spoken of the soul.

Not enjoyment, and not sorrow,

Is our destined end or way;

But to act, that each to-morrow

Find us farther than to-day.

Art is long, and Time is fleeting,

And our hearts, though stout and brave,

Still, like muffled drums, are beating

Funeral marches to the grave.

In the world’s broad field of battle,

In the bivouac of Life,

Be not like dumb, driven cattle!

Be a hero in the strife!

Trust no Future, howe’er pleasant!

Let the dead Past bury its dead!

Act,— act in the living Present!

Heart within, and God o’erhead!

Lives of great men all remind us

We can make our lives sublime,

And, departing, leave behind us

Footprints on the sands of time;

Footprints, that perhaps another,

Sailing o’er life’s solemn main,

A forlorn and shipwrecked brother,

Seeing, shall take heart again.

Let us, then, be up and doing,

With a heart for any fate;

Still achieving, still pursuing,

Learn to labor and to wait.

Sources for the Introduction

[1] J. D. McClatchy, editor. Longfellow: Poems and Other Writings. The Library of America. 2000. Print.

[2] Andrew Hilen, editor. The Letters of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Harvard University Press. 1966.

Commentary on "A Psalm of Life"

The speaker in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s "A Psalm of Life" presents life as an instrument for striving and achievement; he challenges individuals to think and peer beyond the certainty of death and to tirelessly work toward achieving worthwhile goals.

The poem urges readers to take inspiration from the lives of great men of high accomplishments, to act in the eternal now, and to leave behind a legacy ("footprints in the sands of time" ) that will inspire others to follow their own goals on their personal paths through life.

First Stanza: Confronting and Rebutting Pessimism

Tell me not, in mournful numbers,

Life is but an empty dream!

For the soul is dead that slumbers,

And things are not what they seem.

In one of his most widely anthologized poems "A Psalm of Life," Henry Wadsworth Longfellow creates a speaker who is openly and directly confronting pessimism.

The command, "Tell me not, in mournful numbers," immediately heralds a defiant tone, indicating that the speaker eschews the notion that life remains nothing more than an "empty dream."

The speaker opines and asserts that a passive, slumbering soul is "dead" and that appearances can be deceiving—life’s true value is not found in relinquishment of duty or rolling over and playing dead.

Second Stanza: A Declaration of Transcendental Life

Life is real! Life is earnest!

And the grave is not its goal;

Dust thou art, to dust returnest,

Was not spoken of the soul.

In the second stanza, the speaker is declaring that life is real and earnest. He refutes the notion that the graveyard is life’s ultimate destinational goal.

By quoting the Biblical injunction, "dust thou art, to dust returnest," he distinguishes an important, vital difference between the physical encasement and the eternal soul, which confirms that the true purpose of living the life of a human being is to transcend mortality.

In the second stanza, the speaker is declaring that life is real and earnest. He refutes the notion that the graveyard is life’s ultimate destinational goal.

By quoting the Biblical injunction, "dust thou art, to dust returnest," he distinguishes an important, vital difference between the physical encasement and the eternal soul, which confirms that the true purpose of living the life of a human being is to transcend mortality.

Third Stanza: Defeating the Pairs of Opposites

Not enjoyment, and not sorrow,

Is our destined end or way;

But to act, that each to-morrow

Find us farther than to-day.

The third stanza reveals that pleasure, sorrow, and other sense factors involving the pairs of opposites are also not the ultimate aim of existence.

Instead, the speaker calls for active duty and acceptance of responsibilities as the way to progressive evolution. Each day should fulfill some advancement in one's goal, and not merely remain a repetition of mundane activities or a stagnation of routine.

Fourth Stanza: Time Marches On, but Keep On Keeping On

Art is long, and Time is fleeting,

And our hearts, though stout and brave,

Still, like muffled drums, are beating

Funeral marches to the grave.

The speaker then addresses the struggle between human desires and ambition and the relentless onslaught of time as it ticks on and on.

The metaphor of "muffled drums" beating "funeral marches to the grave" emphasizes drearily the inevitability that death continues to approach, yet the speaker continues to urge his fellow human beings to remain "stout and brave" despite these unsavory facts.

Fifth Stanza: Confronting the Battlefield of Life

In the world’s broad field of battle,

In the bivouac of Life,

Be not like dumb, driven cattle!

Be a hero in the strife!

The speaker in the fifth stanza then turns to a military metaphor, likening life to a battlefield. He exhorts readers again not to remain passive or herd-like ("dumb, driven cattle"), but to always strive heroically as they meet life’s struggles and set-backs.

Sixth Stanza: The Importance of the Eternal Now

Trust no Future, howe’er pleasant!

Let the dead Past bury its dead!

Act,— act in the living Present!

Heart within, and God o’erhead!

The speaker now is admonishing his fellows against both relying on the future or on dwelling on the past. The command to "act in the living Present" becomes cardinal to the poem’s message.

The phrase "Heart within, and God o’erhead!" states in no uncertain terms that inner determination and divine protection and guidance are major sources of the necessary strength required to meet all the challenges that life is apt to throw at the human mind and heart.

Seventh Stanza: Emulating the Example of Greatness

Lives of great men all remind us

We can make our lives sublime,

And, departing, leave behind us

Footprints on the sands of time;

In the seventh stanza, the speaker is providing the example of great men to inspire the reader.

The lives of great men of the past and present clearly and convincingly demonstrate that it is possible for each human being to achieve greatness and to leave a lasting mark in the fields of endeavor to which they have been called.

By keeping in clear sight worthy goals and determining to work assiduously to achieve those goal, any individual can surely succeed and leave "footprints on the sands of time."

Those "footprints" are found in the histories of those great men and women who achieved their goals and gave to humankind tangible tools.

One thinks of such people as the Founding Fathers, who worked tirelessly to bestow on their country a document called the Constitution, which would allow the citizens to live in freedom instead of a monarchy or dictatorship.

Or one might bring to mind Thomas Edison with his inventions such as the light bulb that ordinary life uses on a daily basis.

Eighth Stanza: Setting a Positive Example

Footprints, that perhaps another,

Sailing o’er life’s solemn main,

A forlorn and shipwrecked brother,

Seeing, shall take heart again.

The speaker then expands on the idea of a life legacy to all others who may just need a boost to continue marching down their own chosen paths. One need not aim for fame and renown to leave behind those "footprints."

Whatever good one leaves behind can offer hope and encouragement to others who are struggling. This notion emphasizes the importance of setting a positive example for others because one can never know who might benefit by learning about or seeing how hard we worked for our own goals.

Ninth Stanza: Perfecting a Stalwart Attitude

Let us, then, be up and doing,

With a heart for any fate;

Still achieving, still pursuing,

Learn to labor and to wait.

The speaker concludes his psalm with a solemn call to action. He urges his readers to remain focused on their goals and duties, and to remain resilient in facing adversity. He wants his fellows to pursue their goal with great determination.

He also wants humanity to nurture perseverance and patience. He admonishes and

urges his audience to be industrious and resilient, to pursue goals with determination, and to cultivate a stalwart attitude. Each individual must"Learn to labor and to wait" as they continue to pursue and achieve.

A Powerful Musing

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's "A Psalm of Life" remains a powerful musing on the human condition, as it performs its function through a pleasant meter, sophisticated rime-scheme, and motivating calls for action.

Longfellow’s psalm is not merely an harangue against mortality; it offers instead a set of instructions for deliberate living, as Henry David Thoreau insisted that we went to Walden's Pond to learn to "live deliberately."

The psalm's abiding appeal is that it has the ability to inspire readers to rise above despair and lethargy, to act courageously, and to hopefully leave a meaningful legacy of guideposts for coming generations.

Commentary on Another Longfellow Poem

- Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's "Christmas Bells" Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s" Christmas Bells" is a widely anthologized poem that celebrates the winter holiday. It features a phrase associated famously with the Christmas season in its chant, "Of peace on earth / Good-will to men."

This content is accurate and true to the best of the author’s knowledge and is not meant to substitute for formal and individualized advice from a qualified professional.

© 2025 Linda Sue Grimes