Literary Origins: Autonomy in the Kalevala as a means to re-evaluate the tradition of the Western Patriarchy.

The subtle differences of the Finnish National Epic

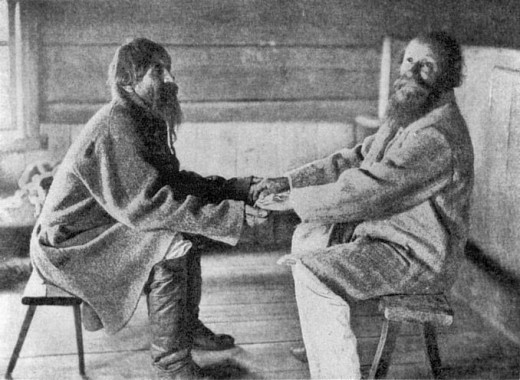

The tradition of oral poetry is shared amongst many ancient cultures, traditions and language families. While there are many similarities, both in the mechanics and the subject matter of these ancient texts, some of the more subtle differences can be extremely enlightening given their significance in understanding the uniqueness of each individual culture and tradition they evolved out of. The Kalevala is a perfect example of how subtle differences in ancient texts can enlighten our understanding of the uniqueness of an ancient culture. In The Kalevala, the characters interact with their entire world in a subtly different and autonomous manner from the rest of western tradition that speaks to their unique understanding of human beings’ relationships with each other, and the world around them. An examination of the subtle differences in the way The Kalevala presents these relationships, in contrast to the traditional concept of the hierarchy that permeates most western tradition, yields not only a firmer understanding of Ancient Finnish tradition, but also, by contrast, comments upon the artificiality of the assumed hierarchy in western tradition.

The subtle differences in both types of relationships mentioned above give shape to a type of autonomy that, at its core, directly conflicts with the traditional, patriarchal hierarchy of western culture. This hierarchy, in most cases in Western History, starts with God, then his Son, then the King and/or the Church, then nobles, then landowners, and finally, the vast majority, workers and serfs. Historical evidence shows that the Finnish people who composed The Kalevala were, for the most part, serfs who were continually invaded and conquered by their neighbors. This placed them at the bottom of the traditional hierarchy in Western History. However, the way these Finnish saw themselves was independent of this vast structure of due submission the outside world imposed upon them. The evidence for and nature of their contrasting view of themselves can be found by examining the nature of the relationships the characters within The Kalevala have with each other and the world around them.

The first of the relationships to be understood is the one between characters within The Kalevala. The most significant difference is in the relationship between women and men. While there is evidence to support the ubiquity of western tradition’s patriarchal understanding of the world, there is also a subtle back current. In poem four, Aino, instead of becoming the traditional young bride, escapes to a different fate. Her mother laments the fate of her daughter, who was turned into a fish, and recognizes her own influence upon the daughter that led to her fate. She admonishes future generations saying, “Do not, wretched mothers, ever, ever at all lull your daughters, rock your children into a marriage against their will” (28). This is not such a subtle break from the ubiquity of arranged marriage, and social expectation upon the female in most western culture. What is more, Aino is allowed to escape the traditional expectation. Her fate is uncertain with relationship to its being better or worse than marriage to Vainamoinen, but it remains uniquely her fate, that is, no one else, or hierarchical expectation, dictated it for her. This is the subtle difference that is most significant because it takes place throughout The Kalevala. This autonomy is characteristic of all interactions between males and females in The Kalevala.

An example of the ubiquity of this autonomy comes with the story of the fate of the girl who escapes Ilmarinen in poem thirty-eight. This also finds resonance in the tasks set before Ilmarinen and Vainamoinen to win the hand of the maid of North Farm and the attitude of the women towards them both before and after Ilmarinen eventually wins the hand of the maid. These examples are not isolated, and therefore, they are indicative of a significant, yet subtle, difference concerning the Finnish ideal of autonomy, and their relationship to things like societal obligation.

This autonomy can be demonstrated further by the examining the subtle differences between the characters’ relationship with the world around them in The Kalevala and the nature of relationships between man and nature that have prevailed throughout Western Tradition. Whereas Western Tradition is informed by the idea that man’s duty is to subjugate or improve nature, the characters in The Kalevala behave as if the world around them has its own concerns, independent of human knowledge and interest. Again, this is another form of autonomy that is in direct conflict with prevailing Western hierarchical views that have traditionally placed nature even lower than women.

Other Epic Poems

Never read The Kalevala? Order it today!

There are many examples of characters personifying objects and parts of nature in such a manner that calls attention to their lack of obligation to human beings. This lack of obligation speaks to an indifference in nature that is in direct conflict with the core of Western Heirarchy, which depends for its very existence upon the obligation of one class to another. An example of this is in poem sixteen, where Vainamoinen has Sampsa search for the right tree to make a boat out of. The significant thing about this is the manner of Sampsa’s search. The trees are personified and Sampsa asks each of them, an aspen, an evergreen, and an oak, “Would the keel of a man-of-war come from you?” (96 & 97). The subtle difference of significance is the fact that Sampsa, in asking the trees if they could be the source of a boat, is acknowledging the fact that it may not be in the tree’s design to become part of such an endeavor, and furthermore, that a tree might have the right to object to this enterprise. This directly contrasts the idea that all the earth is to be improved and of course should therefore be used to create whatever a superior member of the universal hierarchy deems fit to create, be they King or Pope. This questioning by Sampsa suggests a separate fate, or will, something that is inherent in nature that Sampsa, at the very least, recognizes he must respect rather than overpower, even though he has the means to overpower the tree.

This independent fate is parallel to Aino’s and other women of the epic. This parallel strengthens an understanding of the uniqueness of the Finnish tradition and culture from other western traditions. This not only enriches our understanding of how the ancient Finns saw themselves and understood the world, but also is demonstrative of the artificiality of the assumptions of the western patriarchical understanding of the relationships between humans, themselves, and the world they find themselves in. To what end can one re-evaluate the overall climate of Western Tradition by one of its counter currents? The best possible end of this endeavor would be an opening of the mind that recognizes the assumptions we bring with us to the world around us. The fact that these traditions overlap historically validates the comparison as critique of the larger culture. This is not the intent of the Finnish who compiled The Kalevala in antiquity, but it is one of its longest lasting and most significant contributions of their unique National Epic.

Next in the Literary Origins Series

The next hub in this series will examine William Shakespeare's Hamlet as a document of profound linguistic inventiveness. Hamlet is one of Shakespeare's greatest plays, but it's linguistic accomplishments are often overshadowed by elements of plot and character. This is a shame as the document is one of the most linguistically creative documents in English ever.

Check back soon for more literary discussion as there are other posts on the way as well. All comments and questions are welcome. Thanks for reading.