- HubPages»

- Books, Literature, and Writing»

- Literature»

- American Literature

Life Sketch of Sylvia Plath

Sylvia Plath as a Feminist Icon: Notion Dismissed

Before addressing the biographical realities of Sylvia Plath, it is necessary to confront the elephant in the room regarding much of what has been written and disseminated about the poet through the writings of feminist provocateurs.

In expository drivel such as "A Life Written in Invisible Ink" by Sandra M. Gilbert, Gilbert and Gubar's "Infection in the Sentence: The Woman Writer and The Anxiety of Authorship" from Madwoman in The Attic, and Sarah Savittt's "Sylvia Plath and Feminism," Plath's multitudinous, cosmic display of genuine art is demolished to a rubble of feminist ashes.

For example, Gilbert and Gubar lament that the "matrilineal heritage of literary strength and female power have been suppressed, hidden, or kept from [women writers] by patriarchal poetics."

The notion of a "patriarchal poetics" is a meaningless smoke screen, a straw man, erected simply for the purpose of meaningless, bootless illogical combat.

As well, the following Savitt claim limits Plath's true achievements as an poet and artist: "Plath is most powerful when she explores what it means to be a woman in an unequal world – and this is why she is considered a feminist icon as well as a brilliant poet."

Plath's achievements as will be documented in this brief life sketch range far and wide— way beyond the feminist stifling rope with which these narrow-minded critics have tried to lasso the deceased poet's canon.

Plath's issues are human universal issues, not merely female against male domination. For example, in "Devalued Domesticity and Counterfeit Careerism: Marxist-Feminist Reading of Sylvia Plath's The Bell Jar," Alexandra Novoa attempts to show how Plath's narrative about a deeply troubled young woman serves as a exemplar of the damage done society by capitalism.

The Marxist-Feminist alliance takes the struggle of the sexes one step further: woman are not only oppressed by men, they are also oppressed by the "system."

Sylvia Plath's poems, short stories, essays, and one novel continue to attract readers for their emotional intensity, colorful imagery, and brave exploration of the human heart and mind. Her work is far more varied and cosmic in nature than certain feminist critics would have their audiences believe.

Early Life and Education

Sylvia Plath was born on October 27, 1932, in Boston, Massachusetts, to Otto Plath and Aurelia Schober Plath [1]. Her father was a professor in the department of biology at Boston University.

Sylvia's mother, Aurelia Schober Plath, was a first-generation American of Austrian descent. Mrs. Plath served as an associate professor of medical secretarial skills at Boston University's College of Practical Arts and Letters, where she worked from 1942 until her retirement in 1971.

As a child, Sylvia demonstrated academic as well as creative ability. She began composing poems at an early age and published her first poem when she was only eight years old. Her early fondness for literature seemed to predict a lifelong dedication to literary pursuits.

In 1936, the Plath family moved to Wellesley, Massachusetts. Sylvia's father died suddenly on November 5, 1940, only nine days after Sylvia's eighth birthday. This loss deeply affected Sylvia and later influenced several of her later poems.

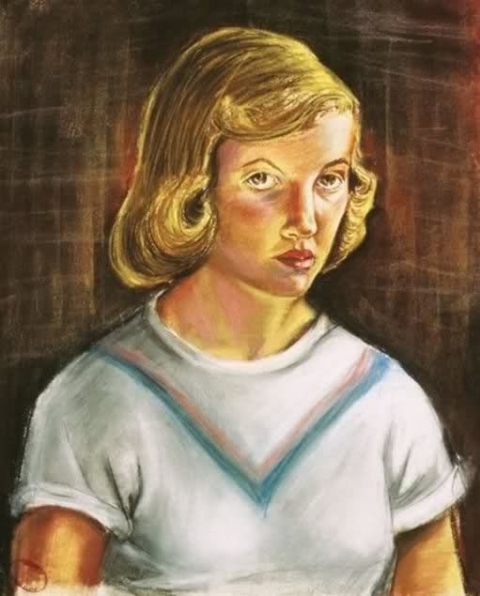

Sylvia attended Gamaliel Bradford Senior High School in Wellesley, where her academic skill continued to develop as well as her literary skill in poetry writing. She remained an excellent student and took up many interest beyond literature. She even dabbled in painting, producing several self-portraits.

After she graduated from high school, Sylvia attended on a scholarship Smith College, the prestigious women’s liberal arts school. At Smith, she continued to show academic success as she remained intensively engaged in her studies.

During the summer of 1953 [2], between her junior and senior years, Plath worked as a guest editor for Mademoiselle magazine in New York City. This experience provided material for her later semi-autobiographical novel, The Bell Jar.

Despite her academic achievements, Sylvia faced personal problems during her college years. She suffered severe mental health obstacles, which led to a period of hospitalization after her first suicide attempt [3]. Sylvia recorded her struggles in her journals and later used those entries to write her fiction.

Despite her struggles with mental illness, Sylvia graduated with highest honors from Smith College in 1955. She then was awarded a Fulbright Scholarship, which allowed her to continue her studies at Newnham College, Cambridge University, in England.

Sylvia's curiosity and academic strength heralded her achievements at Cambridge. She continued to sharpen her skills in writing poems, and engaged with the contemporary literary scene, widening her artistic outlook.

Poetry, Publications, Awards

Sylvia Plath’s literary career was relatively short, but it was distinguished by important achievements. Published in 1960 in England and in 1962 in the United States, The Colossus and Other Poems was the only collection of Sylvia's poems [4] to be published during her lifetime.

This collection cemented her reputation as an important new voice in contemporary American poetry. Reviews of her works fulled up with praise for her distinctive imagery and her skill in weaving complex emotions into clear, concise poetry.

The collection The Colossus and Other Poems heralded the Plathian formal entry into the world of the literary arts.

In 1963, Sylvia Plath's published her first and only novel The Bell Jar under the pseudonym "Victoria Lucas" [5]. This semi-autobiographical work reveals a forceful characterization of mental illness combined with social pressures.

At first the novel garnered little attention but after Plath's death it became a guidepost [6] for understanding the struggles of the poet and the mind-set that was able to craft the calibre of poems that she left behind.

The novel began to resonate widely with readers and was eventually considered a masterpiece.

In 1982, nearly twenty years after her death, Sylvia Plath was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry for her collection The Collected Poems [7]. This once prestigious award recognized the power and quality of Plath's entire canon of poetry. It cemented her place in the literary world.

Plath was, indeed, the first person to win a Pulitzer Prize in poetry posthumously. This acknowledgment emphasized the impact and value of her having secured a prominent place in American literature.

Sylvia Plath’s poetic style changed throughout her career, from formal, traditional structures to a freer, more intensely personal free verse. Her early works often revealed close attention to sound and rhythm.

The Colossus and Other Poems addressed themes of art, nature, and personal identity [8]. Poems such as "The Colossus" and "Medusa" focused on her obsession with structural immensity and feminine archetypes.

Plath's later poems, especially those written in the months prior to her death, are characterized by naked, emotional force, as she creates speakers who address directly their issues.

These works are often classified as "confessional" poems—and play out in the similar atmosphere that surrounds the poems of Anne Sexton.

Other significant Plath collections published posthumously include Ariel (1965), Crossing the Water (1971), and Winter Trees (1971). The collection Ariel [9] is considered Plath's most powerful and thus most influential work.

Poems from Ariel, such as "Morning Song," "Daddy," "and "Death & Co.," engage themes of ambivalence ("Morning Song"), dealing with rage ("Daddy"), and an attempt to use Greek tragedy ("Death & Co."). While uneven in quality, these poems remain noteworthy for their colorful metaphors and rhythmic force.

In addition to poetry, Plath published a number of short stories, essays, and critical commentaries. These prose works further demonstrated her versatility and sharp observational skills [10].

Plath's journals, which were also published after her death, provide further valuable insight into her creative process, her personal struggles, as well as her intellectual development.

Her journals provide information, which assists in understanding her other works. The complete publication history of her work shows the extent of her prolific output, especially considering her relatively short life.

Beekeeping and Ted Hughes

Sylvia Plath had a life-long interest in nature [11]. She dedicated many poems to the results of her detailed observations of plants, insects, and animals, a quality that heralded the poems of Emily Dickinson to the forefront in American poetry.

Four months prior to her death, Plath composed a suite of poems about bees. She explored her nature interest with intensity in her famous "Bee Poems" [12].

She had started a project of keeping bees the year before, and she wrote to her mother an excited letter about attending a beekeepers' meeting in North Tawton, to which she and Ted Hughes had relocated.

Sylvia and Ted had their daughter Frieda at that time, and then her son Nicholas was born in January 1962. Plath beamed in her letter to her mother that the beekeeping would put the cap on the idyllic, rustic life for the young family.

However, Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes' marriage was not without its controversies [13]. Their relationship fostered a consequential personal and artistic partnership, which mutually influenced both of their literary developments and the volume of their output.

Their shared literary ambitions and intellectual pursuits encouraged a creative environment. They critiqued and encouraged each other's work, leading to periods of intense artistic productivity for each partner.

However, the dissolution of their marriage in 1962 and Hughes’s relationship with Assia Wevill attracted much public attention after Plath’s death [14]. This personal trouble has been extensively, and even sensationally, scrutinized.

The controversy has continued to be debated regarding Ted Hughe's editing and publishing of Plath’s work. Scholars and readers have argued over the extent to which Hughes shaped Plath's legacy [15].

Some critics have questioned Hughes' omission of certain poems and journal entries, which seem to suggest that he has tried to paint his own selective portrayal of her life and work.

Nevertheless, in spite these arguments and accusations, the power and originality of Plath’s works remain unquestioned. Her work continues to stand independently as a testament to her unique vision and literary skill.

Death and Burial Site

On February 11, 1963, Sylvia Plath committed suicide in London, England, at the age of thirty. Her death occurred during a particularly harsh winter and a period of personal difficulty [16].

Sylvia Plath is buried in the graveyard at Saint Thomas Church in Heptonstall, West Yorkshire, England. Her gravesite remains a place of pilgrimage for many admirers of her work

The Plathian Legacy

Sylvia Plath’s legacy as a poet is monumental and well established. She continues to remain one of the most treasured and innovative voices in twentieth-century American poetry.

Her seminal work in the "confessional" mode extended the boundaries of poetic expression. She forcefully examined the subject of self-awareness, which has challenged traditional conventional wisdom of privacy in art.

Many critics and scholars continue to scrutinize her technical skill, her extraordinary command of language, and her ability to create engrossing narrative in poetry. Her careful attention to form and to details emphasizes the raw emotional content of her poetic choices.

Unfortunately, some critics have exploited Plath's works to further their feminist complaints against the so-called patriarchy [17]. Focusing on Plath's poem "Daddy," these extremists read into the poem issues that are not there.

In the literary world, Plath is not alone in becoming and remaining a canvas on which critics and scholars can write their own proclivities while ignoring the true accomplishments of the poet.

Still, Sylvia Plath's work is strong enough to withstand the misunderstanding of contrived critical analysis. The proof of her literary power lies in the fact that in 21st century American letters, the Plathian canon continues to garner readers and literary enthusiasts.

Sources

[1] Curators. "Sylvia Plath Biography." Encyclopedia of World Biography. Accessed June 7, 2025.

[2] Michelle Legro. "Pain, Parties, Work: Sylvia Plath in New York, Summer 1953." The Marginalian. Accessed June 7, 2025.

[3] Editors. Sylvia Plath. Biography. April 15, 2021.

[4] Curators. "The Colossus and Other Poems - Summary." eNotes. Accessed June 7, 2025.

[5] Nicky Marsh. "The Bell Jar." Britannica. April 16, 2025.

[6] Oliver Burgess. "The Bell Jar: Sylvia Plath’s Masterpiece of Confessionalism." Writer's Path. July 6, 2021.

[7] Goran Blazeski. "Sylvia Plath was the first person who won a posthumous Pulitzer Prize." Vintage News. December 15, 2016.

[8] Editors. "The Greatness of Sylvia Plath." Library of America. Accessed June 7, 2025.

[9] Editors. "Sylvia Plath’s Ariel: An Appreciation." The Berkeley Beacon. February 13, 20134

[10] Somnath Sarkar. "All Sylvia Plath Short Stories and Prose Writings Summary." English Literature. August 29, 2021,

[11] Nassim Jalali. "How Sylvia Plath’s profound nature poetry elevates her writing beyond tragedy and despair." The Conversation. Accessed June 8, 2025.

[12] Curators. "Sylvia Plath and the Bees." DublinBees. Accessed June 8, 2025.

[13] Aiyana Edmund. "The Tragic Relationship of Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes." Literary Ladies Guide. March 7, 2018.

[14] Claire Fallon. "Ted Hughes' Brother Remembers His Marriage To Sylvia Plath." HuffPost. December 4, 2014.

[15] Paul G. Methven. "Hughes Editing Plath." Academia. Accessed June 10, 2025.

[16] Jennifer Latson. "Why Some Blamed Poetry for Sylvia Plath’s Death." Time. February 11, 2015.

[17] Editors. "Exploring Feminism through Sylvia Plath's Poetry." PoemsPlease. Accessed June 10, 2025.

Commentaries on Sylvia Plath Poems

- Sylvia Plath's "Daddy" Sylvia Plath’s "Daddy" remains the victim of much misdirected criticism. The poem’s speaker is dramatizing the angst caused by her relationship with her father. She, thus, denigrates the man to the point of insisting that he died before she could kill him.

- Sylvia Plath's "Two Sisters of Persephone" Sylvia Plath's "Two Sisters of Persephone" compares the result of virginity vs fecundity on the lives of two specific women: two sisters who live very different lives.

- Sylvia Plath's "Morning Song" The speaker in Sylvia Plath's "Morning Song" is a new mother who is dramatizing her feelings of ambivalence as she begins to take care of her newborn baby. The new mother is facing one of the most awesome tasks placed by God and nature before a woman.

- Sylvia Plath's "Death & Co." "Death & Co." is one of Sylvia Plath's weaker poems, relying heavily on postmodern obtuseness and obscurity; it features seven free verse paragraphs, the final a single line.

- Sylvia Plath's "Mirror" The speaker in Sylvia Plath's masterpiece "Mirror" employs a double metaphor of personifying a mirror and then a lake to report the experience of observing a woman obsessed with the disfiguring of her aging face.

- Sylvia Plath's "Bitter Strawberries" The poem "Bitter Strawberries" by a very young Sylvia Plath displays some intriguing imagery, although the images remain unconnected and are often jolting.

This content is accurate and true to the best of the author’s knowledge and is not meant to substitute for formal and individualized advice from a qualified professional.

© 2025 Linda Sue Grimes