Paramahansa Yogananda’s "At the Fountain of Song"

Introduction and Excerpt from "At the Fountain of Song"

Paramahansa Yogananda’s "At the Fountain of Song" plays out in eight stanzas of varying lengths. The rime schemes enhance the meaning of each stanza’s drama. The poem metaphorically compares the practice of yoga to searching in the earth for a wellspring.

However, instead of water, this special wellspring exudes music. The word, “song," in this poem compares metaphorically the Cosmic Aum sound, heard in deep meditation, to a unit of musical rendering.

Spoken by a yogi/devotee who practices the techniques of Kriya yoga that lead the practitioner to God-realization, or self-realization, this poem focuses on the awakening of the spinal centers that exude sound, as well as light, to the meditating devotee.

(Please note: Dr. Samuel Johnson introduced the form "rhyme" into English in the 18th century, mistakenly thinking that the term was a Greek derivative of "rythmos." Thus "rhyme" is an etymological error. For my explanation for using only the original form "rime," please see "Rime vs Rhyme: Dr. Samuel Johnson’s Error.")

Excerpt from "At the Fountain of Song"

Dig, dig, yet deeper dig

In the stony earth for fount of song;

Dig, dig, yet deeper dig

In soil of muse's heart along.

Some sparkle is seen.

Some bubble is heard;

'Tis then unseen —

The bubble is dead.

(Please note: This poem appears in Paramahansa Yogananda's Songs of the Soul, published by Self-Realization Fellowship, Los Angeles, CA, 1983 and 2014 printings. A slightly different version of this commentary appears in my publication titled Commentaries on Paramahansa Yogananda’s Songs of the Soul.)

Commentary on "At the Fountain of Song"

The devotee in Paramahansa Yogananda’s "At the Fountain of Song" is dramatizing his search for self-realization.

First Stanza: Command to Meditate Deeper

In the first quatrain-stanza, the devotee commands himself to meditate deeper and deeper in "[t]he stony earth," with earth referring to the coccygeal chakra in the spine. Again, the speaker/devotee commands himself to continue his yoga practice, so he will move along the path quickly to liberation.

The speaker is creating a metaphor of his body as the earth, into which earth-dwellers must "dig" to procure the life-giving substance of water. The spiritual seeker is digging into his soul as he meditates to find the spiritual life-giving substance of spirit.

Second Stanza: A Glimpse of the Sought-After Substance

In the second stanza, also a quatrain, the devotee receives just a glimpse of the fountain; it is only a bubble that bursts quickly and then is gone. As the seeker after water would likely get a glimpse of the substance as he digs, the yoga seeker may also detect a "sparkle" now and then.

Beginning yoga practitioners experience exhilaration with their routine but find it difficult to hold that experience, and then they must make a decision to continue or to give up. The work to find water must continue until a gush is found, just as the yogic seeker must continue to seek until he has experienced the union his soul seeks.

Third Stanza: Continuing Awareness

If the devotee continues to "dig," he will begin to experience awareness of the next chakra—the water, or sacral, chakra. In this quatrain, the speaker/devotee again commands himself to dig deeper to make the bubble return.

The devotee has again received just a glimpse, and he encourages himself to continue practicing so that the "bubble-song again [will] grow." As the seeker continues his meditation practice, he finds is consciousness moving up the spine, chakra by chakra.

Fourth Stanza: Seeing and Hearing

The devotee exclaims that he now hears the sound of the water chakra; he metaphorically "see[s] its bubble-body bright." But he cannot touch it, meaning he cannot completely grasp control of the feeling of bliss to which he has ventured very close.

Now he commands his own soul to "Bleed, O my soul, do amply bleed / To dig yet deeper—dig!" The speaker/devotee is spurring himself on to deeper meditation, so he can unite his soul fully with Spirit.

Fifth Stanza: Consuming Peace and Beauty

Hearing again the "mystic song," the devotee becomes consumed with the peace and beauty of the feeling it offers. The "violin tones" continue in unending satisfaction to the devotee. The many songs make the listener feel that they will soon be exhausted, but they are not; they continue without pause.

The speaker grows ever more determined to continue his journey up the spine. Thus, he continues to command himself to dig ever deeper in the spiritual realm until he can bring forth that fountain in its entirety.

Sixth Stanza: Satisfying the Spiritual Thirst

The devotee dramatizes his experience by metaphorically comparing it to drinking a satisfying beverage: "I drink its bubble voice." As the devotee imbibes, his throat becomes greedy for more and more of the soothing elixir. He wishes "to drink and drink always."

The speaker knows that this is the kind of beverage that he can drink endlessly without physical satiation. Only the soul can expand without boundary. Thus, he can command himself to drink without ceasing.

Seventh Stanza: Moving Up to the Fire

After experiencing the "water" chakra through the "mystic song," the devotee’s consciousness moves up the spine again to the "fire," lumbar, chakra: "The sphere’s aflame," because "[w]ith flaming thirst [he] came."

The devotee then spurs himself on again to "yet deeper dig." Even though he feels that he can practice no longer, he is determined to continue. The growing awareness inflames the devotee's desire to know more, to experience more of the deep beauty and peace of the spiritual body.

Eighth Stanza: The Object of Digging

The devotee continues to dig deeper in his meditation, even though he surmised that he had experienced all the bliss he could find. But then the speaker/devotee pleasantly experiences the "undrunk, untouched" fountain.

Through the speaker/devotee's faithful and determined effort and practice, the object of all of his "digging" has come into view. The overflowing fountain of song inundates the devotee with its refreshing waters. He has successfully unearthed his goal and is free to bask in the bliss of its waters.

Related Paramahansa Yogananda Information

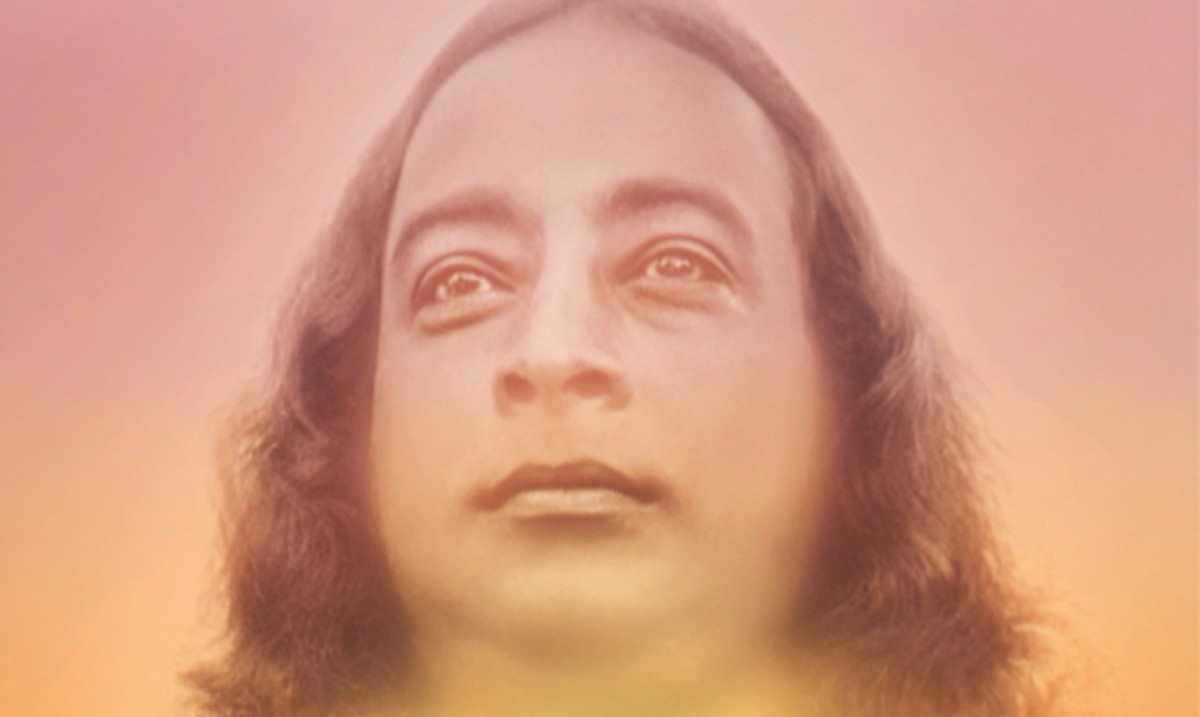

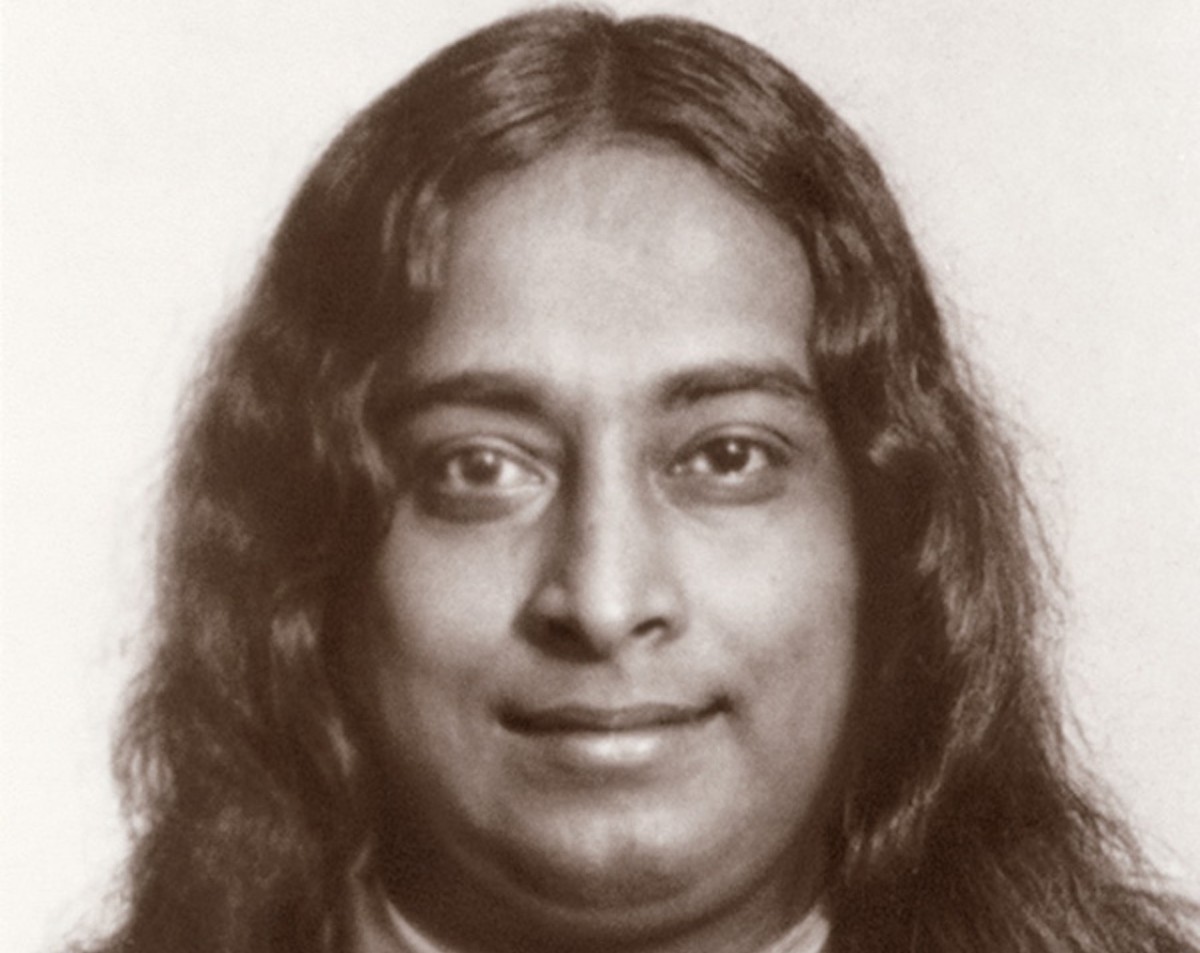

- Life Sketch of Paramahansa Yogananda: Father of Yoga in the West Paramahansa Yogananda is the monastic name of Mukunda Lal Ghosh. The sources for this brief life sketch of Paramahansa Yogananda are his Autobiography of a Yogi and the official Self-Realization Fellowship website.

Commentaries on Paramahansa Yogananda Poems

- Paramahansa Yogananda’s "Consecration" In the poem titled "Consecration," which opens Paramahansa Yogananda’s collection of spiritual poetry "Songs of the Soul," the speaker humbly consecrates his works to the Divine Creator. He also lovingly dedicates the collection to his earthly father.

- Paramahansa Yogananda's "The Garden of the New Year" In "The Garden of the New Year," the speaker celebrates the prospect of looking forward with enthusiastic preparation to live "life ideally!"

- Paramahansa Yogananda's "My Soul Is Marching On" This inspirational poem,"My Soul Is Marching On," offers a refrain which devotees can chant and feel uplifted in times of lagging interest or the dreaded spiritual dryness.

- Paramahansa Yogananda’s "When Will He Come?" How to stay motivated in pursuing the spiritual path remains a challenge. This poem, "When Will He Come?," dramatizes the key to meeting this spiritual challenge.

- Paramahansa Yogananda’s "Vanishing Bubbles" Worldly things are like bubbles in the sea; they mysteriously appear, prance around for a brief moment, and then are gone. This speaker dramatizes the bubbles’ brief sojourn but also reveals the solution for the minds and hearts left grieving for those natural phenomena that have vanished like those bubbles.

The Voice of Paramahansa Yogananda

The Importance of a Spiritual Classic

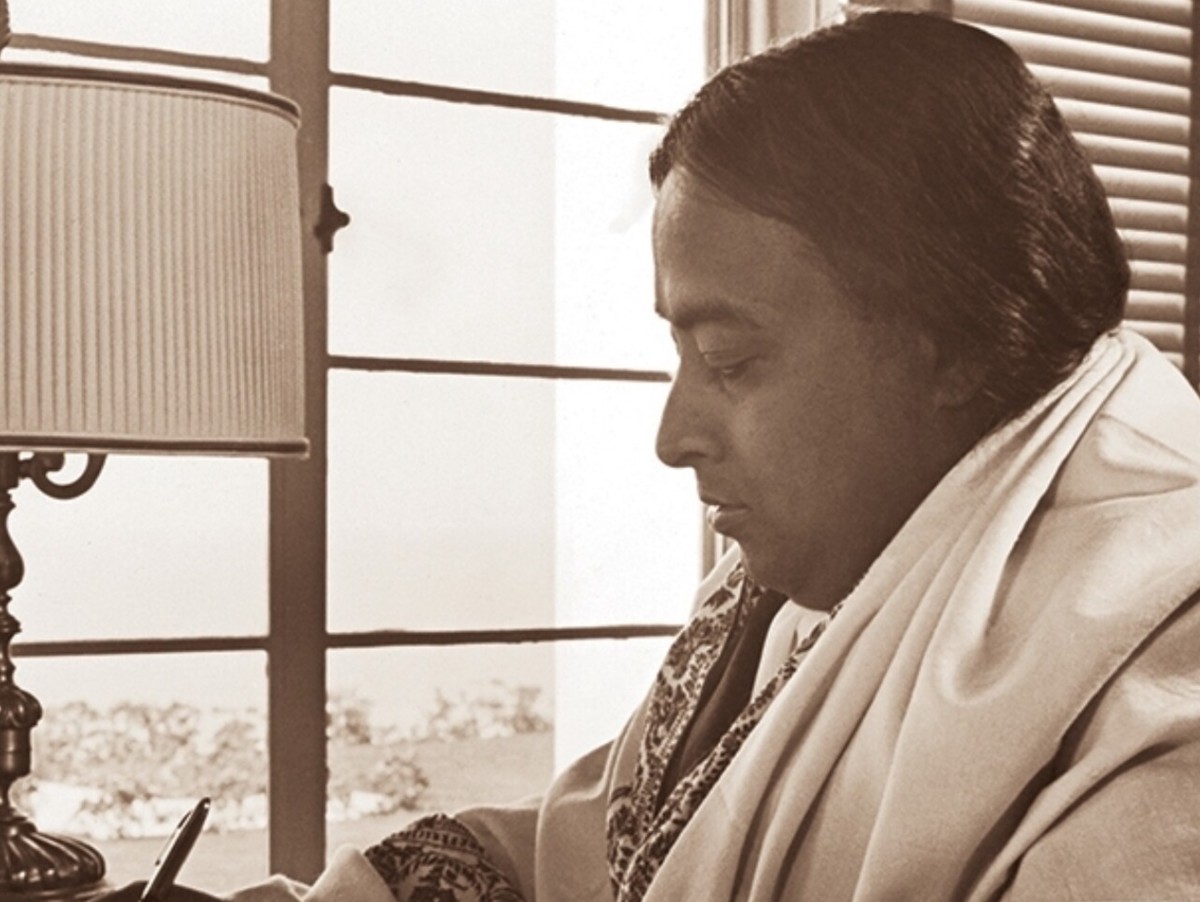

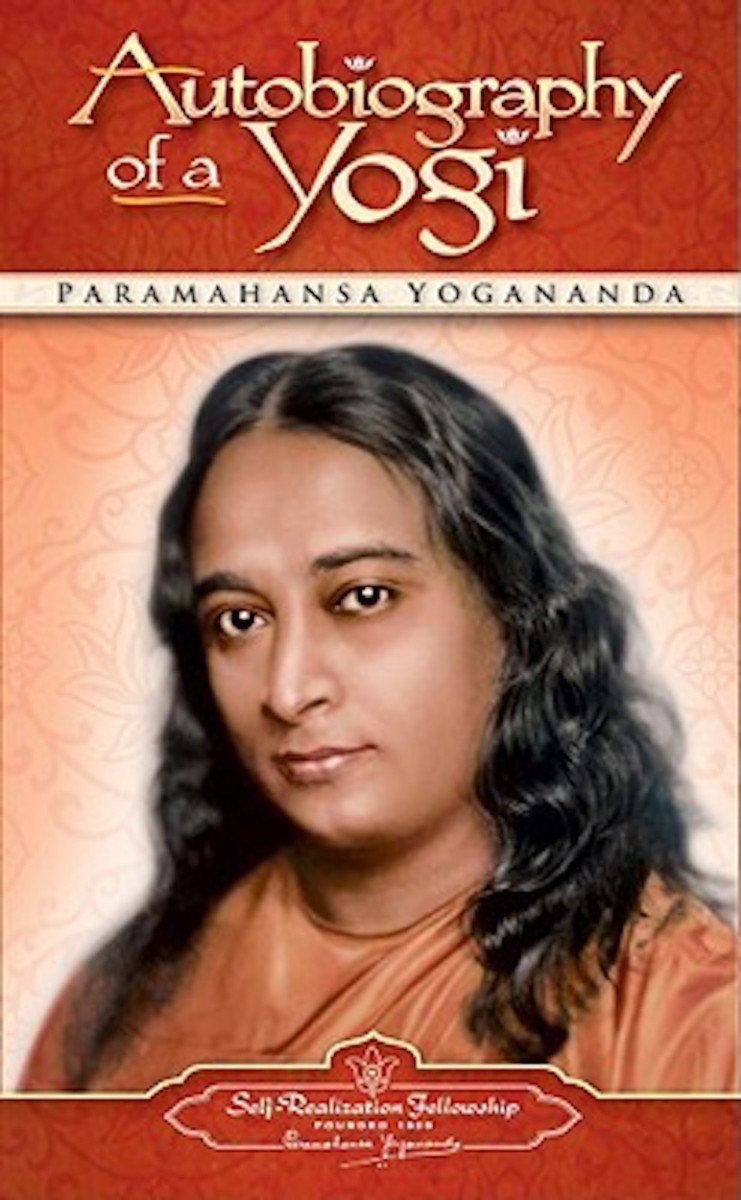

In 1977, my husband Ron and I went on one of our book shopping trips. I spied a book, Paramahansa Yogananda’s Autobiography of a Yogi, and I recommended it to Ron because he liked biographies.

Strangely, I said to him about the man on the cover: "He's a good guy!" Strange, because I had no idea if the individual was a good guy or not, being the first time I ever saw him.

So, we purchased poetry books, and we also purchased the autobiography for him. He did not get around to reading it right away, but I did, and I was totally amazed at what I read. It all made sense to me; it was such a scholarly book, clear and compelling.

There was not one claim made in the entire 500 plus pages that made me say "what?" or even feel any uncertainty that this writer knew exactly whereof he spoke.

Paramahansa Yogananda was speaking directly to me, at my level, where I was in my life, and he was connecting with my mind in a way that no writer had ever done. For example, the book offers copious notes, references, and scientific evidence that academics will recognize as thorough research.

This period of time was before I had written a PhD dissertation, but all of my years of schooling including the writing of many academic papers for college classes had taught me that making claims and backing them up with explanation, analysis, evidence, and authoritative sources were necessary for competent, persuasive, and legitimate exposition.

Paramahansa Yogananda's autobiography contained all that could appeal to an academic and much more because of the topic he was addressing.

As the great spiritual leader recounted his own journey to self-realization, he was able to elucidate the meanings of ancient texts whose ideas have remained misunderstood for many decades and even centuries. In a nutshell, this book changed my life—a change that I needed and for which I remain truly grateful.

This content is accurate and true to the best of the author’s knowledge and is not meant to substitute for formal and individualized advice from a qualified professional.

© 2025 Linda Sue Grimes