- HubPages»

- Books, Literature, and Writing»

- Commercial & Creative Writing»

- Creative Writing

Of Pebbles, Politics, Mind, and Matter: Chapter 5

The story so far:

The application of the results obtained from a mind-mimicking algorithm developed by Charuchandra Chimalgi based on his theory of thought, launches him on a roller-coaster-like ride - elevating him to the heights of ecstasy and sending him hurtling down to the depths of despair many times over and across many situations. Read on to find out how Charuchandra negotiates yet another undulating path in his life, this time involving the potent nexus of corrupt politicians and the underworld.

If you wish to revisit the first chapter at this point, please click on the following link:

If you wish to revisit the second chapter at this point, please click on the following link:

If you wish to revisit the third chapter at this point, please click on the following link:

If you wish to revisit the fourth chapter at this point, please click on the following link:

If not, please scroll down to read the fifth chapter titled "Institutional Thought".

Chapter 5: Institutional Thought

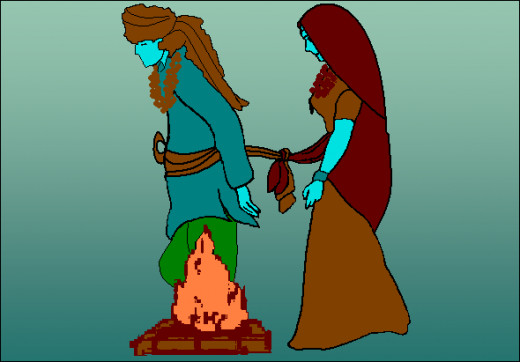

Charu and Snigdha were married not long after he was elected to the state legislative assembly. It was a grand wedding, yet there was nothing ostentatious about it. There wasn't even a father-in-law to grace it, as neither the bride nor the groom had a father. And there was only one motherly figure who was the foster-mother of one and the mother of the other. It was a huge climb down for Charu, after having six pairs of prospective parents-in-law pursuing him relentlessly for almost a year. The people of the city and its outskirts too celebrated the wedding of their representative, heartily and in abandon. Streets were festooned, music blared, food was generously consumed, and liquor rained plentifully for the day - down the throats of the revelers.

While the city and the outskirts reveled, Charu and Snigdha sat hand-in-hand by the pond bank in their ancestral house. The pond, over which no individual or institution seemed to have a legal hold going by official records, had been appropriated as the private property of the new member of the legislative assembly by some overzealous official. None objected to it, however, because Charu had been the exclusive user of the water body for years now, and he had been the only one who stood by it during its times of misery and decay, while the rest of the neighbors had shut their doors and windows to it. A high wall had been constructed around it and the banks planted with a lot of greenery. It was an idyllic place for newly weds to rejoice in the bliss of their togetherness. Included in the package as a bonus, was the pleasure of throwing pebbles into the pond's pristine waters. The official who had the pond appropriated for Charu, also had the water body dredged, the sedimented pebbles removed and washed, and re-heaped along the banks. Even with two persons indulging in this exotic pastime now on a regular basis, there were sufficient pebbles to last for a couple of years or more, at least.

"Don't you think it is meaningless for the entire city and its environs to be celebrating our wedding day in this manner?" asked Snigdha, happy to have found quietude, after the morning's ordeal that was given the name of a wedding ceremony.

"I agree, dear. But what baffles me is the fact that not all who celebrate do so wholeheartedly. Left to themselves, at least half the populace, if not more, would prefer having a quiet and peaceful time. There is no reason for them, as individuals, to join the celebrations, despite their preference to the contrary. If I were to compute the probable decision of one such individual using my model, I am certain that the decision would be one of staying back home in solitude or doing something exclusively. Abstract institutions - marriage and its celebration, for instance - seem to have a decision making ability of their own which override individual thought in certain areas. Depending upon the potency of their traits, they alter the decision of individuals to an appropriate extent. I should probe this phenomenon and include its ramifications into my algorithm," declared Charu.

Snigdha rued the moment she decided to bring up the topic. But she also knew that the general tenet, which was impressed upon newly wed women and which stated that the path to a man's heart is through his stomach, would not apply to Charu. The path to this man's heart was through his brain. She had to keep it fed with ideas to crunch, thoughts to chomp, and concepts to chew, if she wanted to rule the other two organs of her husband; the stomach and the heart would follow the brain obediently.

"I believe that you should investigate an institution that is at a higher level than marriage and I suggest that you consider religion as your focus of study. Marriage is partly institutionalized by religion and its mores are almost entirely defined by it. There are very few individuals not swayed by it," remarked Snigdha, putting her well-thought-out decision into practice.

"That is a great idea indeed, Snigdha!" exclaimed Charu. "My education on the manner of flow of women's thoughts seems to be yet incomplete. I wonder whether my model would have come up with the suggestion that you just did, had I attempted to mimic your thoughts using it."

"That is why it is still a model and not reality," said his wife, smiling at him.

"But coming back to the topic of investigating religion as an institution and its influence upon the decision making process of individuals, I would like to begin with the definition of religion and developing our arguments from there. Are you ready for a long night of discussion?" asked Charu.

"Why not?" responded Snigdha.

The peaceful precinct of the pond and its proximity, promoted a ponderous yet playful procession of philosophical thought along the promenades of their probing minds late into the evening of their wedding night and almost upto day break the following morning. Their marriage was consummated in the cozy niche of their minds, in the warm comfort of their hearts, and the energetic atmosphere of their brains. The bed lay desolate and forlorn.

"What is religion, as you understand it?" asked Charu.

"A set of tenets that specify dos and don'ts and also an argumentative basis for arriving at those tenets for its adherents, assuring them a happy life here and hereafter, if they were to strictly and conscientiously follow them," replied Snigdha.

"That is as good a definition as can be," commended Charu, truly impressed with his wife's answer. In all these long years of association, he had never let her come emotionally close, immersed as he would be in his own thoughts and theories. This was the first time that he was seeing her as a comrade, colleague, and conversationalist, and he was pleased and delighted with what he saw, heard, and experienced.

"Then tell me, why are there so many religions?" asked Snigdha.

"Three motives that I can see for their proliferation are regional atmospheric conditions, differences in terrain specific priorities, and time specific societal circumstances. These give rise to a set of tenets that make life easier, simpler, orderly, and harmonious for people who live within these bounds. When one or more of the three defining parameters change with time, and the tenets are found to have outlived their usefulness and applicability, the religion either dies - spawning others to replace it, or falls prey to a more dominant religion suited to the times and climes and succumbs to its might."

"But there should be some underlying idea that is common to all religions - not as humans define it, but as nature directs it, is it not? What do you think that fundamental driving force is? God, perhaps?" asked Snigdha.

Charu was even more delighted by his wife's incisive and logical thinking when she asked this, but her mention of God, dampened his euphoria a little.

"I am sorry, dear, but I am not very comfortable with certain three-letter words. We would rather keep it out of our discussion, unless it is absolutely necessary," remarked Charu.

Snigdha wasn't unaware of his predispositions and knew exactly what he was hinting at. "You shouldn't be so unyielding and uncompromising, Charu. It will be difficult to discuss anything, if it is so. I respect your stand, but you should respect mine as well. We can certainly debate it and if proven wrong, I am willing to endorse your stand," she said.

Charu realized that he had gone overboard, and apologized. He offered to clarify his rather inflexible stand upon what he felt was a reasonable platform.

"Let me explain my personal 'belief' about God, in the context of how it is described by any of the prevalent religions, or those that may have existed in the past or may come into being in the future. I include the past and future too, because religion necessarily is based on a subjective dogma and such a dogma can never be all-inclusive and universal. It needs to define a set of things as 'desirable' and those outside this set as 'undesirables.' The concept of God is merely a convenience, as so many other conveniences that humans have created to negate, overcome, or neutralize their seeming inconveniences, and more importantly to give credence to the dogmatic tenets. God, as we have been taught by any religion, is a human creation - not the other way, as we are led to believe. It may be argued that if something exists, it has to be created, and so there should be a creator. The limitations of our experiences cause us to conclude thus. In the same breath, we also talk of eternity. If existence were eternal, then it doesn't need a creator. It doesn't need to be created, because by definition, it is eternal. By logical extrapolation then, there doesn't need to be a creator. Has adherence to this perspective made me less sad or more happy? No. Because, I too am a prisoner of my innate traits that define, power, and shape my thoughts, as it is with everyone else. If God is a convenience for some, this perspective is one for me. I prefer this because I search for logic and reason in everything," concluded Charu. At least twenty pebbles would have found their way into the pond waters during this long monologue.

There was a short pause, while both of them went over what Charu had explained, a few times - the listener to compose an answer and the speaker, to gather more arguments to buttress his position, should there be a prolonged confrontation of ideas.

Snigdha found his arguments acceptable. While supporting Charus's position, it provided others the flexibility to hold their own.

"I suppose I should apologize too for saying that you were being too rigid in your stand," said Snigdha. "There appears to be no cause for a difference of opinion at all." An argument that threatened to mar the unique marital bliss that the newly wed couple were enjoying, petered out into nothingness and in its place was installed a state of mutual appreciation and admiration - the bedrock of a long and happy married life.

Their briefly stalled discussion on religion and its influence upon individual thought continued from the point where it had been suspended.

"You asked me whether there was some underlying notion that is common to all religions, as nature directs it and not as humans define it, was it not?" asked Charu, restarting the dialogue.

"Yes."

"Firstly, I do not think that there is any necessity to differentiate between nature and humans, because the latter are a product and part of the former."

Snigdha thought for a few moments and expressed her concurrence. "I agree," she said.

"Coming to the underlying notion, I believe that the process of evolution is the mother-of-all religions. It has a very uncomplicated dogma with two simple elements - propagation and preservation. All beings are adherents of this religion, without exception. It is an eternal religion - or atleast will be around until evolution is replaced by its opposite process 'dissolution,' whose tenets would be 'devastation' and 'destruction.'"

Snigdha shuddered. "If religions spawned by the process of evolution can be as destructive as they are, then I dread imagining the influences and effects of religions that are a product of the process of dissolution," she remarked.

"You needn't worry about that. Our thoughts would be appropriately attuned to that environment, if we were to be a part of it. We would enjoy living in such an environment too," stated Charu.

"One can then justify the clash between the lesser religions under the process of evolution, as each imbibes the main and only trait of this primary religion, and perseveres to propagate and preserve itself," said Snigdha.

"Yes, and within a given religion of the lesser kind, this perspective also provides an insight into why women accept religious tenets more wholeheartedly than men. For men, the urge to adhere to the tenet of the higher religion - propagation, is stronger and bindings that come in the way are looked upon as impediments to their pursuit and brushed aside. For women, these very bindings provide a protective atmosphere to nurture and raise their young - the act of preservation," stated Charu.

"Perhaps evolution itself has made a distinction in the allocation of activity by making males primarily responsible for propagation and females for preservation," observed Snigdha.

Charu then told her about his deduction of a primary notion each, for men and women - the concept of 'only' and 'also' - that would point to their direction and content of thought.

"I suppose, we could equate 'propagation' with 'only' and 'preservation' with 'also', in this context. Isn't it fascinating that the inconceivably complex world around us works on the basis of two simple principles?" commented Snigdha.

"Theoretical supposition is all very fine, Snigdha, but tell me; do you as a woman truly enjoy all those rituals that are prescribed by religion? Frankly, most of them appear nonsensical to me," said Charu.

"To be honest, I too do not agree to some of the rituals that are in vogue, which seem out of place in the present context. Women still hold fast and don't let them go easily, because they would be going against their intrinsic quality, if they were not to strive to preserve them. However, should a situation arise, where a ritual were to go against the larger theme of preservation of the offspring or the self, then I am sure women too would not brook a ritual being a hindrance."

It was almost dawn, and the newly-weds rejoiced at the wonderful nuptial entertainment that they had been granted. It had brought them together in spirit as nothing else ever could. They now completely understood themseleves, each other, and the world around. Their hearts rippled in harmony, as did the waters of the pond, when the couple threw a pebble each together into it for the last time during that long night and retired for the morning and an extended day's sleep.

* * *

The glow of incense sticks was all that was visible for a brief while, when the lights were switched off at the prayer hall, amidst the loud chant of hymns by the swaying devotees seated on the floor. When the lights came on again, seated on his peacock shaped throne in undignified splendor was the self-styled god-man, who had become a sensation in recent times in the city. The naïve and ecstatic devotees gasped and baulked. The sensation was just about magical to witness the almost instantaneous appearance of the god-man and his throne from nowhere and without any sound. This was an every-evening happening at the sprawling modern hermitage that had sprung up within a matter of a few months on a barren stretch of land on the outskirts of the city.

The power, speed, and reach of modern technology, though talked about, had not been fully comprehended by the general populace, and when its effects were presented with a dramatic flair, it appeared to be nothing less than magic, and the man who made it happen to be none less than a god-man, if not God himself.

He called himself "I." It was another reason that attracted people to him. While regular run-of-the-mill god-men sported long-winding names, this one had a one letter appellation, something unheard of in the annals of "god-manning." His justification for this was that to vanquish anything, one had to confront it with its own like. Ego - represented by the notional importance of the self and the concept of "I," was the one great encumbrance on the path to salvation. If one were to annihilate it, then the purpose of life would have been achieved. He accomplished this by naming himself "I," which made people refer to him as "I," rather than themselves, and achieve instant salvation. This was the age of instantaneous things - instant food, instant communication . . . Why should the process of salvation lag behind?

The effect of this maneuver on I’s part was telling.

Devotees stopped referring to themselves as “I.” If their god-man was I, how could they also be? They would refer to themselves in third person and it set them on the path of instant salvation. The practice had its uncomfortable repercussions too. The instantaneously-unbonded-ether-surfers began changing English grammar. Sentence constructions like, “I has said so . . .,” came into widespread use. Parents, among the followers of I, began insisting that their children follow this norm with their school lessons too, making it a nightmarish experience for their teachers.

Their identity having been unconsciously usurped by another, devotees didn’t realize that their material possessions too began to follow the same path in the wake of their pioneering self. In their supposed blissful path to salvation, they failed to appreciate the reality that they were being reduced to penury, while I’s hermitage began to glow in opulence and grandeur, rapidly.

It is an immutable law of nature that everything grows to its level of uselessness and then collapses. The more rapid the growth, the earlier is that level reached, and the faster is the collapse.

Some of the earliest pioneers among the devotees began to glimpse a desolation, rather than the promised kingdom of heaven, when the situation reached the stage of not being able to provide for their children or themselves any longer. The instincts of preservation took possession of their thought processes, exorcizing the ghost of salvation.

I, who knew well the rules of the game and its repercussions, having played it many times before, and who maintained a constant tab on potentially deviant souls, roped in the right mix of specialists – which included malleable medicos, pliable politicians, acquiescent administrators, and compliant criminals, to encourage and urge those erring from the salvational trail, to return to it. Those who refused, realized their objective of getting off it, but were never heard of again.

Expressions of muted protests and dissent were easily dealt with by this able band of manipulators. But they couldn’t contain the spread of a general feeling of melancholy among the devotees. They could suppress lamentation with force, but couldn’t induce gaiety using the same means.

Rivals of I, sensed their opportunity to get even. This disposition in them was not caused by any personal enmity. They were business rivals. I, who seemed to have concocted a perfect combination of product mix and business plan, had cornered a disproportional market share of gullible persons, while the others had to be satisfied with the meager leftovers. He seemed invincible when the going was good. The break that the rivals had been hoping for, appeared to be around the corner now, and they decided to make the best use of it.

A few representations to the government on behalf of some of the aggrieved but suppressed souls, prompted a reaction from the lawmakers and law keepers. I, who had a finger in every broth, believed that he could easily ride out the investigation, on the strength of his well-wishers on both sides of the societal divide. His friends in the government prepared the ground for such an eventuality by conniving to have a political committee set up to probe the charges against god-man I, rather than making it a police case, which would have given the matter a criminal hue. Hoping to render the probe even weaker, they decided to make a first-time and apparently inexperienced member of the legislative assembly to head the committee, who could be easily influenced to make favorable decisions. Their choice was Charuchandra Chimalgi.

* * *

Charu was delighted when he was informed about his selection. The first few months of his life as an elected representative in the legislative assembly had been rather sedate. There were a series of valedictory functions, where associations that represented diverse interest groups vied with each other to be seen as the most loyal of followers. Political pundits, media moguls, and seasoned soothsayers had predicted that Charuchandra would scale great heights in the political firmament and glow for long, shedding his munificent light of wisdom and good deeds upon the populace. In the light of such a near-unanimous forecast, it was only natural that people found Charu to be an ideal repository for enduring investments of support and goodwill.

Even though he had improved upon his earlier speech-delivery skills, Charu was found woefully wanting when it came to addressing a gathering. This greatly disturbed party strategists and they considered it to be one liability that would soon begin to erode Charu’s current popularity. Some tried to use this counsel as a means to impose their proxy as a spokesperson for the congenitally tongue-tied people’s representative, who saw through their machinations and resisted the moves. But he also realized that he had to find his own solution to the problem and fast. It was his mother who came to the rescue with a simple yet profound suggestion.

“Why don’t you draft Snigdha as your spokesperson? I am sure that the party will have no objection, though some individuals may be disappointed. With your popularity at its peak at the moment, you can easily have your way and push your resolution through. None would dare oppose or contradict you openly,” said she, one day.

“But mother, Snigdha prefers and needs to be by your side now. Your health is failing,” objected Charu.

“Getting a dedicated and caring nurse for me is far easier than arranging a good spokesperson for you. For once, listen to me and do as I say,” commanded the mother.

“Do you feel comfortable with mother’s proposal?” Charu asked his wife, who stood listening to the altercation between mother and son.

“To be honest, I am terrified,” replied Snigdha. “But it also sounds exciting and gives me the chance of being with you more often. If mother approves of it, I am willing to give it a try.”

As expected, there were a few frustrated and glum faces, when Charu announced his resolve at a party meeting two days later. Neutral party seniors, who had nothing to gain or lose from this, immediately endorsed it, and the arrangement became official.

Snigdha had never recognized this dormant talent in her, but beginning with short and tentative speeches, she was soon to blossom into an effective orator. It was during this process of her transformation that Charu was called upon to shoulder the responsibility of heading the committee to look into the charges of wrongdoings against god-man I.

* * *

I’s conspiratorial conglomerate of officials and criminals, worked out a comprehensive strategy of containing the committee chief Charuchandra Chimalgi. It had carrots, sticks, and an assortment of other goodies and baddies thrown in. It was assumed that such a wide range of inducements and deterrents would be adequate to beguile, bemuse, befuddle, batter, and bludgeon the neophyte into submission.

Charu, on the other hand was equally prepared. Having gone through the report on the charges against god-man I, he found the behavior of the devotees unacceptably diverging beyond norms. He concluded that I had cleverly contrived to equate the notion of salvation with that of preservation. In fact, he had made the former idea appear even better; shrewdly promoting it as a means of everlasting preservation. This also justified the proportionately large number of women among his followers. He didn’t consider the possibility beyond the capability of god-man I, of conjuring up an apparently authentic link between the concept of propagation and salvation as well. He believed he could put a reasonable one together himself with a bit of effort. God-man I being a pastmaster at such work, would accomplish a better and more effective job and with much less effort. The catch seemed to be in making it work. Men generally being single-track operators needed more convincing to change track. Women being multi-taskers, it was easy to gain entry into their minds and then build upon, particularly if the theme that one wished to impress was associated with the concept of preservation. By Charu’s inference, it was this difference in approach and endeavor that prompted I to focus on women. It made better business sense to obtain higher returns with minimal input.

On the morning that he was to officially take over the chairmanship of the committee, a memo reached Charu identifying the room allotted to him in the assembly annex. It was room number six. The chairman-designate baulked. The number raised visions of difficult times to come; of being taken to the brink and then brought back. He frantically attempted to have his room changed, but to no avail. All others were occupied and every occupant had some form of affinity or the other to the number of his or her room and refused to entertain Charu’s request. The frustrated newly appointed committee chairman did the next best thing possible. He accepted his plight as a directive of destiny and prepared himself for yet another ordeal. It was the comforting thought that he would come through it unscathed and perhaps stronger, that made him do so. He had no choice.

Within a few minutes of his occupying his seat in the allotted room, Charu received a call from one of the officials, who was part of I’s network.

“Mr. Chairman, congratulations on your assuming office. The Revered I, graciously invites you to his hermitage and requests your presence there in the evening at 6 pm. Please make it convenient to come,” said an even voice, sounding neither friendly nor hostile.

“Who is this calling?” asked Charu.

“Your senior colleague, Hemant Rajvanshi.”

“Thank you for the invitation, Mr. Rajvanshi, but why is it that I am getting it from my colleague who is a member of the governing party, rather than from a staff of the hermitage? I would have been happier, if this request had come from Mr. I, himself.”

“We refer to the great personage as, ‘The Revered I.’ It would be better if you did so too. We should give the respect and esteem that is due to others, if we wish to maintain our own, is it not Mr. Chairman?” said the voice, a bit coldly now.

"I would have no problems if you were to address me as Charu. And don't expect me to call you by any other name but Hemant, however senior you may be. The name that I use to address you has nothing to do with your seniority or my lack of it. Your rank and mine are public knowledge and none can demote you or elevate me without a reason. It also does not mean that I do not respect or regard seniority. As to Mr. I, it will be for me to decide whether I call him by his name, or tag an endearment to it - at the front, or back. It will entirely depend upon my impression of him and his conduct towards me," retorted Charu. He was not the one to be so curt with a stranger. But the peremptory lining in the other man's manner and tone of expression had raised his hackles.

"Being rude leads to trouble, Charu," said the voice, even the vestigial civility in it having vanished.

"You already are, Hemant."

"Are you, or are you not, coming to the hermitage this evening?" demanded the voice.

"I have already set my agenda according to the protocol that needs to be followed under the regulations and conventions of my commission. I will be meeting the two named aggrieved parties first, and then summoning the accused to demand an explanation. And you do not fit into this scheme so far, Hemant. I will contact you, if there is a need for it during the enquiry," said Charu and disconnected.

Both conversationalists were silently fulminating at their respective ends, when the dialogue ended. Neither had expected it to go this way at the time it had started, and both were left frantically recasting their strategies to deal with the new contingency.

Charu didn't feel as confident as he did when he was on the phone. Hemant Rajvanshi had sounded too much like his late uncle for comfort. On the spur of the moment, he set up the decision-mimicking program on his laptop, loaded the module that he had developed to imitate his late uncle's thoughts, and fed in details of the current situation, to view the situation from his perspective.

The cursor blinked, as the processor crunched bits close to the speed of light.

The result was as he had anticipated. "Eliminate those whose presence on the scene may lead the trail to your doorstep. Break the interfering investigator's bones as a warning."

The committee-chairman was shaken. Though his saner-self reminded him that such an outcome was dependent on the correctness of his assumption that Hemant Rajvanshi or perhaps, I himself, would have a disposition very similar to that of his late uncle. But his other self, not so convinced with this argument, pushed the panic button.

Charu called the Home Minister in the State Government under whose jurisdiction this committee had been constituted and recorded his complaint against his senior colleague. It was good that he did so, for the minister immediately called up the named person and asked him to go easy on the young man. It was not because he had a soft corner for the new member of the legislative assembly. He only wanted to nip in the bud any controversy that had the potential of snowballing into something unmanageable. The government survived on a narrow majority and the opposition was waiting in the wings only for such irritants to affect defections from the ruling party ranks and assume power. At the moment, it was politically expedient to keep things under control.

The Minister also advised Charuchandra not to take things to heart and be pragmatic. "Live and let live, is the best policy of life. Follow it in letter and spirit and you will go places, young man," he said.

"What about the commission of enquiry then?" asked Charu. "Am I not to discharge my duty, as you obviously are?"

"Do so by all means, Charuchandra, but make what I said your guiding principle."

"Yes, sir. Thank you," the young man acknowledged, and decided to moderate his earlier stridency. However, he felt that he should warn the two families on whose behalf the complaints against I were lodged, to be on guard against strangers and restrict their movements for some days, until things cooled down. He believed that, if the other side were to notice that he was not being very serious about his earlier resolve, they would restrain their impulse towards some precipitate action as well. He also hoped that the realization that someone was beginning to take note of their activities would make them less severe towards their victims.

Charu called Jerry Ranga and asked him to locate the residences of the two complainants. He then went personally to each of them, cautioned them to be careful for the next two weeks, and assured them that their grievances were being looked into. His visits, however, did not go unnoticed by the other side. Jerry, who had been asked to post his men to keep an eye on the aggrieved parties, reported that there were other spies too posted there. He had located their handler through the underworld grapevine and had found out that they were under the employ of I.

"You are pally with the guys from the other side too, is it?" asked Charu bewildered.

"It is an unwritten law of the underworld that we do not consider another of our kind an enemy, even if we work for and owe our allegiance to different handlers. Our loyalty and commitment is to the promise that we give to our handler with respect to the job and this unwritten law - in that order of precedence. He didn't tell me what they were assigned to look for, and I didn't tell him what my brief was. The arrangement is helpful at times and is a hindrance at others, but as that is the rule, it has to be followed."

"Who sets the rules?"

"It is like a religion and has been followed across generations," explained Jerry.

"Ah! The underworld religion. Fascinating," remarked the impressed surface-dweller. "Tell me, Jerry, did my late uncle follow these rules?"

Jerry laughed. "He was both God and religion, and played by his own rules. Such conventions apply only to us lesser beings."

"I see. It is the same as it is in the world above, where god-men, or at least the errant ones among them, don't need to follow the rules that they set for others," said Charu.

“Yes. But there are good devil’s agents too in the underworld. Almost as good, if not better, than the god-men above,” declared Jerry with conviction.

“I don’t dispute that, Jerry. It certainly is, as you say. I was only wondering at the kind of sway institutional thought has over an individual. Often, they seem to override the latter, making the individual vulnerable. Perhaps, that is nature’s way of keeping in check runaway correct decision making. To maintain balance, there have to be as many wrong decisions as the right ones. A winner is one, only if there is a loser.”

“Right you are, Charu,” agreed Jerry Ranga.

* * *

It was a very contemplative Charu, who narrated the day’s incidents to his wife, late in the evening after dinner. What followed was another glorious and memorable night in their marital life, by the pond side, throwing pebbles into its placid waters and discussing the persuasive power of institutional thought over those of an individual. Though the heat of the verbal exchange of the morning with god-man I’s representative, appeared to have abated with the setting-sun – he still had a nagging premonition that it was just the proverbial calm before the axiomal storm that momentarily devastated his life, whenever the number six was associated with any activity of his.

Charu started the discussion by confiding to Snigdha about his anxiety and reservations on the matter. He had also not mentioned to her about this strange connection with a particular number in his earlier discussions, which he did now.

“Have you attempted to use this supposed link with number six to your advantage by forcing it on an event of your choice?” asked Snigdha.

“Yes, I have, and it hasn’t worked so far,” replied Charu.

“How would you then explain it and what would you attribute it to, until you happen to obtain a more convincing explanation? Could it be destiny?”

“As I have said before, in my opinion, concepts such as destiny, god, eternity, and the like, are conveniences into which one can deposit ideas that defy an explanation on the basis of our current understanding. I would go further and say that each of these conveniences have two bins – ‘Known and unmanageable,’ and ‘Unknown and unmanageable.’ For instance, the moment the number six confronts me during the course of some endeavor, I can foresee the consequences to follow, but can do nothing about it. Such phenomena would go into the first bin. I have no idea absolutely about how this link with the number six works. Not all events connected with this numeral, which include those that I have contrived, have taken me to the brink. But those that have were always connected with it. Obviously there is something more to it, which at the moment is unknown and unmanageable, and hence would go into the second bin.”

“In which of these two bins is your conceptual and analytical understanding of the triple-I phenomenon – Influence of Institutional thought on Individuals, currently placed?”

“Hey! That is a nice acronym,” observed Charu. “The triple-I is in neither of the bins. It is on my work table and is unlikely to go back into any of them.”

“You mean to say that you are completely satisfied with the modifications that you have made to your model to include it in the decision making process?”

“Yes, almost.”

“How does the model account for the differences in the levels of intensity of devotion to an institution like religion, across individuals, which makes them respond to a situation differently?”

Charu briefly described the nuances of his original model, explaining the three divisions of memory and their role in the decision making process, and then added, “I believe that the unconscious comes seeded with a collection of information, which defines the individual’s primary responses towards every class of stimulus. It is here that the quantum of devotion and dedication that could be demonstrated towards a broad range of concepts will also be stored. As the conscious mind is gradually filled up with information of experiences, the primary responses of the individual would be tempered by the contents of conscious.”

“This would imply that your late uncle would not have had any devotion recorded in the unconscious region of his memory. Is it not?” asked Snigdha.

“Yes and no. His level of devotion to himself would have been set at its maximum, while levels of devotion directed at everything else, would have been marginal. When it came to concepts closely associated with preservation, it would have been non-existent. It was because of this that he did not flinch when it came to killing himself,” surmised Charu.

“In your theory, to what would you attribute the initial seeding of traits as packets of information in an individual’s unconscious region of the brain,” asked Snigdha.

“It can only have a genetic basis, and I am beginning to suspect that someone in god-man I’s organization is having a genotype similar to that of my late uncle,” opined Charu, the misgivings of the morning suddenly flooding back.

“I believe that you are getting paranoid about this, Charu. The stress of your first constitutional job is getting to you. Just relax. Everything will be alright,” said Snigdha soothingly, holding his hand.

* * *

A call from Jerry Ranga the next morning confirmed that Charu’s premonition wasn’t without a basis. It had rained heavily around daybreak and the sky was overcast adding to the melancholy of the atmosphere.

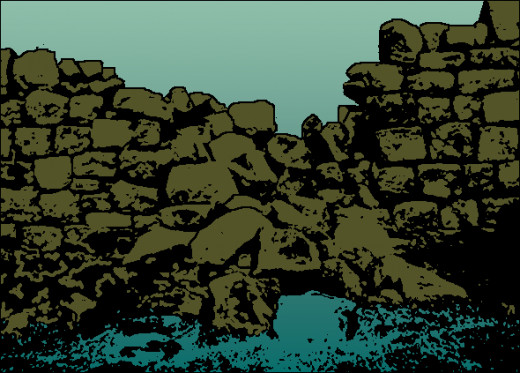

“Charu, I have bad news for you. Three of the four members of one of the families that we had under surveillance have been killed in a wall collapse at a place of worship close to their residence. When they ventured out together, early in the morning, my men cautioned them not to go, or delay their outing, until there were more people moving about on the roads. They refused to heed our words, saying that it was a place of divinity that they were going to and nothing would happen. My men tailed them but did not go into the place of worship. A short while afterwards, a wall inside collapsed with a deafening sound. My men hurried in to find three of the family members dead under the debris. They rushed the fourth, a little boy, to a nearby hospital, where he is battling for life.”

“Do you suspect foul-play?” asked Charu.

“Yes. We asked the caretaker and the guard at the place of worship about the state of the wall that had collapsed. They said it was no doubt an old structure, but not so weak to have fallen due to the recent downpour.”

“No clues of anyone having forced it to collapse?”

“None. At least nothing conclusive. Whoever has done it, has done a neat job. They seem to have chosen the perfect place and time to execute their plan.”

“Increase your surveillance on the other family, Jerry. They could be the next target,” cautioned Charu and hung up. He felt miserable and felt that he was partly to blame for this turn of events. Had he kept his cool while dealing with Hemant Rajvanshi the previous day, this would not have happened.

Remorse soon gave way to wrath. He resolved to go after I and his despicable horde, no matter what happened to him. He called up the Minister for Internal Security to convey his suspicion.

“Sir, it is Charuchandra this side. I seek to put on record that it is I who is behind the mishap today morning,” he began, without preamble.

“Young man, you are either out of your mind or your English needs improvement,” said the Minister, putting the caller immediately on the defensive, though he perfectly understood what Charu was alluding to. He was a well-entrenched and experienced politician who knew how to handle such situations adroitly.

“Sir, I meant to say that god-man I is behind this. The incident should be probed.”

“Do you mean to say that I am not doing my job properly?”

“No, sir!” said Charu, going red. He realized that he had let his frustration get the better of him and pushed himself into a corner.

“The police department is doing its job, Charuchandra. Be assured that if there is any evidence found against the person you allude to, then action would certainly be taken.”

Charu felt the need to do something immediately and decided to visit the other family once again. As a people’s representative and now as the chairman of a constitutional committee, he was entitled to a government vehicle with a chauffeur, which made his movements easier, unlike earlier. When he reached his destination, he found a somber crowd gathered there. Jerry Ranga was there with his men and came forward to meet Charu, as soon as he alighted from his vehicle.

“What is wrong here?” asked Charu.

“They got the members of this family too. They were an elderly couple,” replied Jerry.

“I told you to keep a strict watch . . .” began Charu, but was cut short by Jerry.

“We made sure that they did not leave the house. The other side was smarter. They sent a man in disguise. He came dressed as a priest. We stopped him and asked the couple whether they knew the priest. The man in disguise gave some reference, which the couple believed and asked him in. The guy appears to have administered poison to them and quietly walked away. There were shouts for help from the couple as the poison took effect and they were gasping for breath. When some passersby and my men reached inside they were already in their last throes and died shortly thereafter.”

“Jerry, this is war. God-man I has thrown down the gauntlet and I am picking it up. Get me every detail possible about him and that henchman of his, Hemant Rajvanshi. The information should be with me by this evening,” bellowed Charu in his loudest possible voice.

* * *

Chapter 6: The Warped War

Chapter 7: Thought and Event Chains

Chapter 8: Bonding and the Bonded

Chapter 9: Made-to-order Conscience

Chapter 10: To the Brink and Beyond