Robert Frost’s “And All We Call American”

Introduction and Excerpt from "And All We Call American"

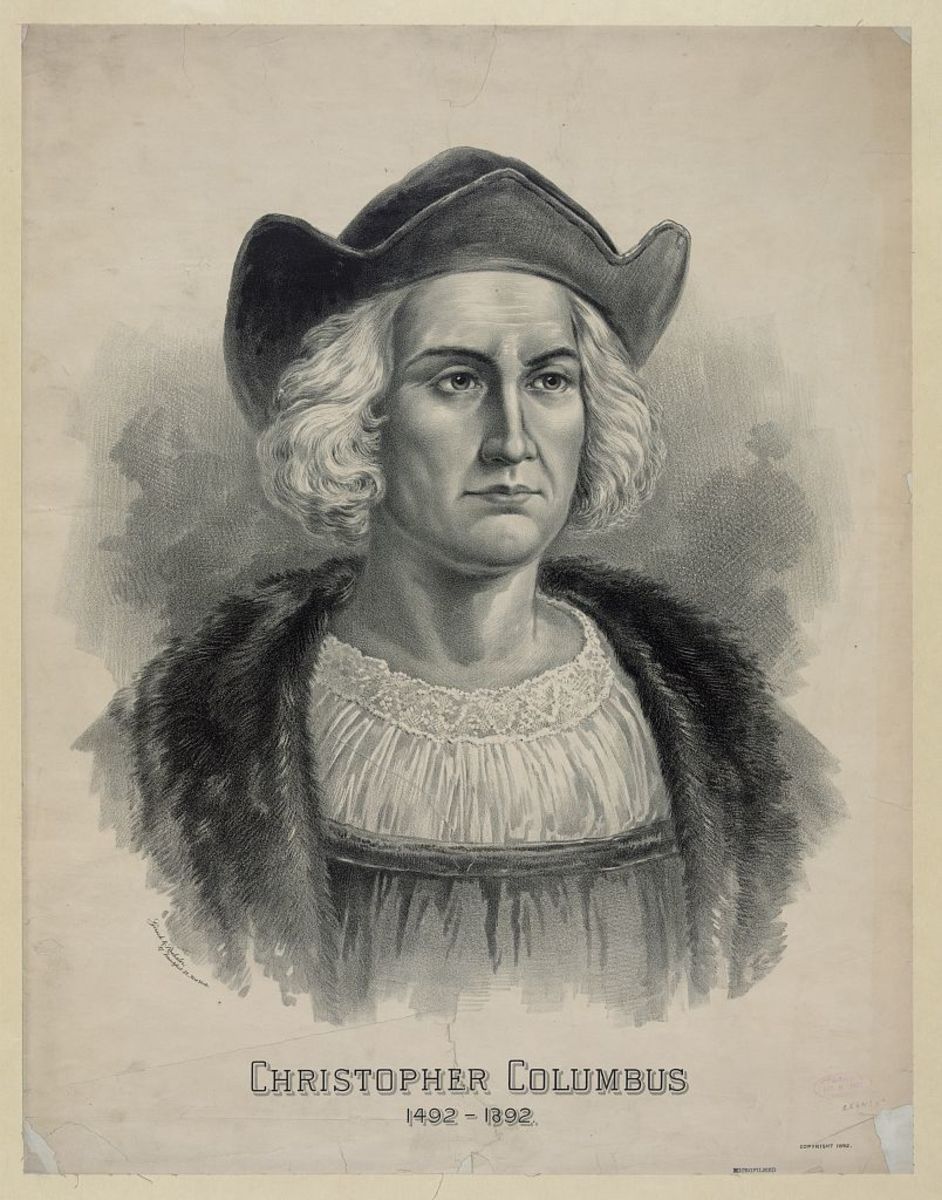

The speaker in Robert Frost’s poem “And All We Call American” attempts a retelling of the familiar story of Christopher Columbus. In so doing, he questions the legendary heroism of the explorer.

No one can deny that the miscalculation of landing on what is now the North American continent instead of the South Asian country of the exploration’s intent—India—opens itself to a certain level of scrutiny.

But the ultimate consequence of the discovery greatly outweighs the unintended nature of the discovery. The importance of the North American continent, particularly the United States of America, for the world remains undeniable.

Despite the current failure to appreciate these Western values keepers, those values continue to uplift cultures from the dire straits of physical and moral poverty.

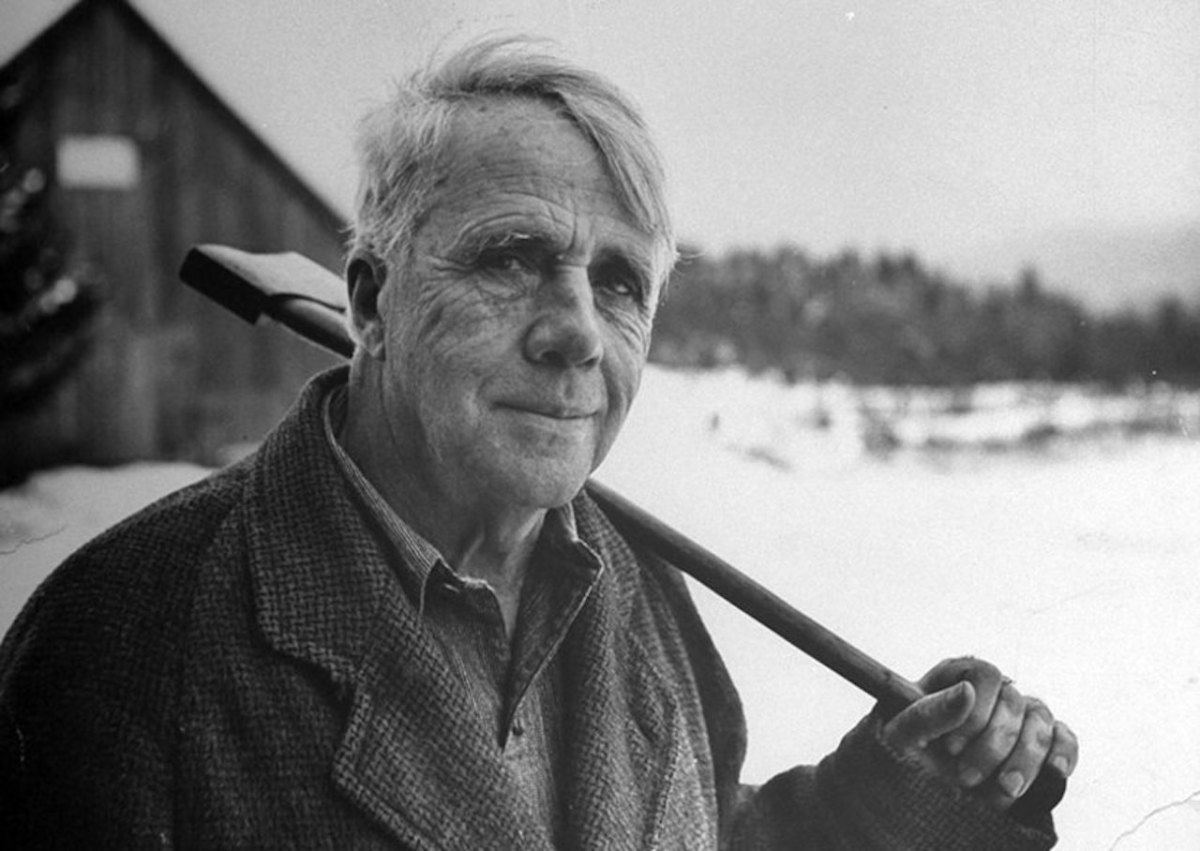

Frostian Curmudgeonry

Even as he took on the reputation of a belovèd poet of nature and human feeling, Robert Frost remained a life-long contrarian and a specialized curmudgeon. Thus instead of celebrating the Columbian legendary figure who opened up the Old World to a New World, he has his speaker concentrate of the limitations of the explorer.

That Columbus was not capable of imagining what the United States of America, Canada, and Mexico would become is not a particularly egregious failure. Excepting clairvoyants, no one else of the time period would have been able to predict any better.

While Frost has attempted to produce a poem that is both historical and philosophical

by having his speaker employ the Columbian expedition, the poem’s cranky bitterness ultimately says more about the speaker/poet himself than about the objective nature of the significance of the voyage of Christopher Columbus.

Excerpt from "And All We Call American"

Columbus may have worked the wind

A new and better way to Ind

And also proved the world a ball,

But how about the wherewithal?

Not just for scientific news

Had the queen backed him for a cruise.

Remember he had made the test

Finding the East by sailing West.

But had he found it ? Here he was

Without one trinket from Ormuz

To save the queen from family censure

For her investment in his future.

To read the entire poem, please visit "And All We Call American" at The Atlantic.

Commentary on Robert Frost’s “And All We Call American”

The speaker in Robert Frost’s “And All We Call American” attempts to play down the Columbian heroic status by castigating the great explorer for not having the ability to predict the future.

First Stanza: Promise vs Problem

Columbus may have worked the wind

A new and better way to Ind

And also proved the world a ball,

But how about the wherewithal?

Not just for scientific news

Had the queen backed him for a cruise.

In the opening stanza, the speaker refers to the Columbian legendary mission that confirmed the scientific theory that Earth was round and that one could end up in the East by sailing West.

The speaker then throws shade at the feat by implying that not enough loot had been procured from the journey: after all, the queen was not especially interested in confirming a scientific theory; she wanted gold, spices, and other goods that usually took an arduous overland journey to reach her part of the world.

At this point, the speaker has introduced a conflict, placing bold discovery against material possession. Because that conflict is inherent in nearly every worldly endeavor, to complain about it, or even point it out, is somewhat naïve.

Second Stanza: Discovery vs Disappointment

Remember he had made the test

Finding the East by sailing West.

But had he found it ? Here he was

Without one trinket from Ormuz

To save the queen from family censure

For her investment in his future.

In the second stanza, the speaker spotlights Columbus’ achievement of sailing west to get to the East. He then poses a question: what did the explorer really find? But then he jarringly shifts to the material possessions that the queen was expecting by claiming that the explorer brought back not even “one trinket from Ormuz.”

The Ormuz trinket becomes a symbol for the Eastern wealth that the queen had been counting on. The speaker implies that the queen’s family would not be happy with her for backing such an unprofitable “investment.”

Third Stanza: Columbus’ Miscalculation

The speaker now shows clear disdain for Columbus for not recognizing that he had not landed in India. The speaker imagines that the mariner searching the barren coasts for the Indian riches and not finding them simply remains perplexed.

The speaker emphasizes the fact that Columbus not only managed to be off by a degree or so, but that he was off by a whole ocean. The speaker seems to take glee in revealing such an error by such a brave man, who has in fact sailed over a whole ocean and has now discovered a heretofore unknown land.

Thus the speaker’s lack of empathy and imagination are revealed more than the fact that the a brave sea-farer had failed to reach India.

Fourth Stanza: Da Gama’s Success

The speaker now doubles down on his Columbian criticism. While Columbus returned home without riches in tow, the explorer Vasco da Gama came home with gold from Africa.

The speaker’s harsh tone furthers his grift against the brave Columbus. By concentrating on material wealth, he is sure he has a good case for humiliating the failed Columbus by playing up the success of da Gama.

But that comparison in hindsight levels the criticism to failure, for the voyage of Columbus is much more widely known than that of da Gama. The importance of da Gama’s gold pales in comparison to the importance of the Columbian discovery of a whole New World.

Fifth Stanza: The Absurdity of a Missed Bluff

The speaker now presents the ridiculous notion that if Columbus had been smart enough, if could have told the queen and any others dejected by lack of material riches that he had discovered a place where the future of humanity might reside.

Such a notion is patently absurd. The speaker is looking back about five centuries, castigating a man for not realizing that a place called the United States of America would provide a “fresh start for the human race.”

The line if “Columbus [had] known enough” demonstrates a level of ignorance that borders on the profane: In any endeavor, it is not necessarily the amount of knowing that is important; it is the nature of the knowledge. He is decrying Columbus for not being prescient, a seer, a clairvoyant.

To cover the fact that he is calling for Columbus to predict the future, the speaker positions the notion that the mariner could have used a “bluff” to suggest the future importance of his discovery. Such a notion remains petty and irresponsible and again shows more about the speaker/poet’s mind than it does the reality of history.

Sixth Stanza: A Youthful Misreading of Columbus

The speaker now inserts a phony self-deprecation. He admits that he once upon a time thought of Columbus as a hero, but now he recognizes that since Columbus was not able to predict the value of the New World he had discovered, then credit for his accomplishment of actually finding that New World should be withdrawn.

The speaker is attempting a bait and switch operation. By claiming that Columbus could have “fooled them in Madrid” the speaker is again referring to the “bluff” suggested in the preceding stanza.

But he then seems to be confessing to being deceived by the Columbus legend. The issue is not however that the speaker/poet was deceived; it is that now the speaker wishes to denigrate an Italian-American hero, and he is reaching beyond reality to form the basis for that derogatory image.

Seventh Stanza: Room and Doom

The speaker now goes completely off the rails. Adding to Columbus’ inability to predict the future is the idea that even if he had bluffed his peers about the future of a New World, what he actually did was just give the world population more room to spread out and be mean.

Such a suggestion implies that if people had just remained in the Europe, Africa, and other reaches of the known world, they could have worked on learning to kind to one another as they continued to live in a “crowd.”

Again, such a suggestion is not only naïve, but it does not take into account that human nature remains the same whether humans are spread out or in a crowd. There is/was no such phenomenon that learning to be “kind” was postponed by the discovery of a New World. Did the folks who remained in Old World learn to be “kind”?

According to this line of thinking, they should have. But again the speaker has come up with a notion this is absurd, while exposing his real purpose of smearing 15th century explorer.

Eighth Stanza: Columbus’ Rewards

The speaker’s gross depiction of Columbus having been thrown in prison and receiving little attention crosses into the obscene. First, through instrumentality of the corrupt Francisco de Bobadilla, Columbus was sent back to Castile in “chains.”

But the Bobadilla’s abject lies about the explorer became immediately obvious, and Columbus was released and restored to his earlier prominence. And the claim of “small posthumous renown”—places named for him—is mind-numbing.

There are over 6000 places in the United States alone named after the explorer. Virtually every state in the USA has a town, city, park, or some landmark named after Christopher Columbus: some “small posthumous renown”!

Ninth Stanza: The Restless Ghost of Discovery

In this stanza, the speaker concocts sheer fantasy that would make today’s Columbus bashers proud. Every creative writer has the unleashed opportunity to foist onto historical figures their own proclivities.

The lame narrative in this stanza is immediately revealed with the vague “They say.” Who are they? How reliable are they? Well, “they” are the demons living in the imagination of the curmudgeon infested brain of the speaker/poet.

Tenth Stanza: Modern Discovery

Here the speaker is not really predicting anything. He is merely setting up another pin to bowl down with his castigation of a fifteenth century man being unable to see into the future.

That Columbus could not image what the United States would look like in the 20th century is hardly an earthshaking discovery. But the speaker is no doubt self-congratulatory for implying that if Columbus has thought to sail through the Panama Canal he would have been on his way to discovering the real India.

Eleventh Stanza: Elusive America

The speaker then takes a dramatic shift from beating up on Columbus to asserting the daft opinion that “America is hard to see.” Besides the flabby language, signifying less than nothing, it makes a brainless claim.

Because anything that extends for miles beyond human vision would be “hard to see,” one might as well say a railroad, New York, or the ocean— each is hard to see. But the speaker seems to be trying to say that America is not only a place but is also a political entity that continues in a mysterious vortex.

Thus the “literary chatter” suggests that “America” cannot be expressed clearly in words.

Twelfth Stanza: Columbus’ View of America’s Advancement

The speaker now makes a delusional claim that Columbus’ selfishness would blind him to the genuine causes of America’s development—that is, if the explorer were able to see America in its current iteration.

The speaker has no idea how Columbus would view the advances in the modern technological influence of “tractor-plow and motor-drill.” That he would impute such an attitude to the explorer is beyond damnable.

Thirteenth Stanza: A Speaker’s Obtuseness

This stanza again is just another putrid display of a speaker whose own jealousy is out of control. Criticizing a historian figure through the lens of an contemporary set of scruples just does not work in a piece of discourse purporting to be a poem.

Fourteenth Stanza: The Futility of Defaming Hero

The final stanza serves as a monument to the failure of the speaker’s position so eloquently laid throughout this piece of drivel masquerading as a poem, for in this stanza the speaker is pretending to predict the future.

The future finds the explorer reaching Asia only to be rebuffed and rebuked because the Asias are tired being “looted” and “disrupted.” And lastly, Columbus will be humiliated that Cortez was so successful in conquering the Aztecs.

The sheer fantasy falls apart immediately because no such voyage was ever made by Christopher Columbus; therefore, he could not have been rebuffed and rebuked by people tired of being “looted” and “disrupted.”

In classical rhetoric such a concoction is called a straw man, fashioned solely for the purpose of burning it down. The speaker fancies an exploration that never existed simply to ridicule it for having failed. If an event is never begun, it cannot be considered to have failed, just as it cannot be deemed to have succeeded.

Robert Frost’s Worst Poem

Robert Frost’s “And All We Call American” is without a parallel; it is Frost’s absolute worst poem. The only quality that keeps this piece from being an contemptible piece of doggerel is the fact that it was composed one of the world’s most noted and beloved poets.

Taking as his subject Christopher Columbus, Frost creates a speaker who reveals a deficiency of thought that seems remarkably reminiscent of adolescent self-absorption.

Instead of celebrating the remarkable discoveries of the great explorer, this speaker chooses to downplay achievement, offering in its place ignorant criticism that Columbus living in the fifteenth century was unable to know what would take place the 20th century.

When a fine, reputable poet throws out a sinker like this one, the only reason for studying such a piece is to understand the complex inconsistency of the human brain.

If a student or novice poetry reader begins a study of Frost with this one, that individual has in store a shocking experience in discovering Frost’s later works such “The Road Not Taken,” “Birches,” “Bereft,” “The Gift Outright,” and “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening.”

Related Robert Frost Information

- Life Sketch of Robert Frost Taking his place among luminaries such as Dickinson and Whitman, Frost has remained one of the most widely anthologized American poets of all time. His poems are more complex than simple nature pieces; many are "tricky—very tricky," as he once quipped about "The Road Not Taken."

Commentaries on Robert Frost Poems

- Robert Frost’s "The Road Not Taken" Robert Frost's "The Road Not Taken" has been one of the most anthologized, analyzed, and quoted poems in American poetry. It has also remained one of the most misunderstood and thus misinterpreted poems in the English language.

- Robert Frost’s "Birches" Robert Frost's "Birches" is one of his most famous poems. It features a speaker looking back on a boyhood experience that he cherishes and would like to do again. Unfortunately, this "tricky poem" has suffered ludicrous readings that insert onanism into its innocent nostalgia.

- Robert Frost’s "Carpe Diem" The phrase "carpe diem," meaning "seize the day," originates with the classical Roman poet Horace. Frost's speaker offers a different view that questions the usefulness of that idea. This poem offers a sample of the themes and the style in which Frost wrote most of his more successful poems.

- Robert Frost's "Bereft" Robert Frost's poem "Bereft" displays one of the most amazing metaphors to be encountered in poetry: "Leaves got up in a coil and hissed, / Blindly struck at my knee and missed." Like "The Road Not Taken," however, this poem offers up a tricky feature.

- Robert Frost's "Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening" Robert Frost's "Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening" remains simple, but the repeated phrase, "And miles to go before I sleep," gives room for Interpretation. Many of Frost's poems possess a tricky element, and he quipped about "The Road Not Taken" being "very tricky."

- Robert Frost's "Departmental" The speaker of Frost's oft-anthologized "Departmental" observes an ant on his picnic table and imagines a dramatic, little scenario of an ant funeral. The use of personification and the pathetic fallacy mixes a colorful drama suffused with human arrogance.

This content is accurate and true to the best of the author’s knowledge and is not meant to substitute for formal and individualized advice from a qualified professional.

© 2025 Linda Sue Grimes