Standard English and Non-Standard Dialects

A Codified Form of English

Standard English can be defined as the codified form of the English language that is widely accepted as the norm for formal communication, education, and public discourse in English-speaking countries.

Standard English is characterized by its adherence to grammatical rules, standardized vocabulary, and a pronunciation that is broadly intelligible across regions, often associated with the Received Pronunciation (RP) in Britain or General American in the United States.

Primarily, Standard English is employed by educators, professionals, government officials, and media personnel who require a uniform linguistic framework to ensure clarity and mutual understanding in diverse settings.

Standard English also serves as the linguistic basis in academic writing, legal documentation, and international communication.

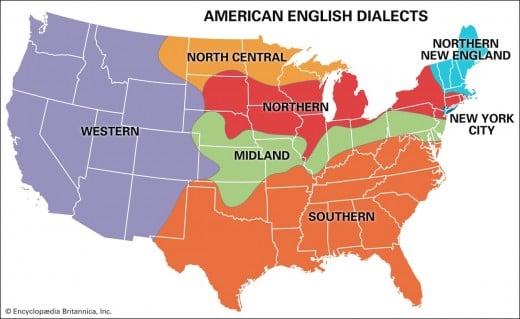

However, alongside this standardized variety exists a rich tapestry of non-standard dialects—regional, social, or ethnic variations of English that deviate from the prescribed norms.

These dialects, often stigmatized as "non-standard" or "non-standard," reflect the cultural identities and lived experiences of their speakers.

The concept of Standard English emerged historically through processes of linguistic standardization, notably in Britain following the establishment of printing presses in the 15th century and the subsequent codification of grammar and vocabulary in the 18th and 19th centuries [1].

Influential works such as Samuel Johnson’s A Dictionary of the English Language (1755) and Robert Lowth’s A Short Introduction to English Grammar (1762) played pivotal roles in shaping this standardized variety [2].

Standard English is not inherently superior to other dialects in a linguistic sense; rather, its status is a product of social, political, and economic forces that may appear to privilege certain speech communities over others.

Non-standard dialects, by contrast, are typically associated with working-class populations, rural communities, or marginalized ethnic groups.

While these dialects may lack prestige in formal contexts, they are linguistically complex and rule-governed systems in their own right, capable of expressing nuanced meanings and cultural identities [3].

Non-standard dialects are often misunderstood as degraded forms of English, yet they represent vibrant linguistic traditions. Examples include African American Vernacular English (AAVE also known as Black English), Appalachian English, Cockney, and Scottish English (Scots).

Each of these dialects deviates from Standard English in phonology, syntax, and lexicon, yet they remain mutually intelligible to varying degrees with the wider community.

The distinction between "standard" and "non-standard" is thus less a matter of linguistic merit and more a reflection of societal attitudes toward power and prestige.

Comparative List of Terms and Phrases

To illustrate some of the differences between Standard English and non-Standard English, the following presents a comparative list of terms and phrases from Standard English alongside their equivalents in some of the most noted non-standard dialects.

Below is a curated selection of Standard English terms and phrases juxtaposed with their counterparts in AAVE, Appalachian English, Cockney, and Scots. These examples highlight lexical, phonological, and syntactic variations while demonstrating the richness of dialectal diversity.

Greeting

Standard English: "Hello, how are you?"

AAVE: "Yo, what’s good?" – Here, "yo" serves as an informal greeting, and "what’s good" replaces the standard inquiry about well-being [4].

Appalachian English: "Howdy, how you holdin’ up?" – "Howdy" is a traditional Southern greeting, and "holdin’ up" reflects a regional expression for coping or faring [5].

Cockney: "Alright, mate, how’s it goin’?" – "Alright" is a common Cockney salutation, and "mate" denotes familiarity [6].

Scots: "Hullo, whit’s the craic?" – "Whit’s the craic" translates to "what’s happening?" with "craic" borrowed from Gaelic [7].

Food

Standard English: "I’m going to eat dinner."

AAVE: "I’m finna grub down." – "Finna" (from "fixing to") indicates intent, and "grub down" means to eat heartily [4].

Appalachian English: "I’m fixin’ to have supper." – "Fixin’ to" is a regional marker of intent, and "supper" often replaces "dinner" [5].

Cockney: "I’m off to scoff me tea." – "Scoff" means to eat, and "tea" refers to an evening meal [6].

Scots: "I’m awa tae hae ma denner." – "Awa tae" means "going to," and "denner" is the Scots term for dinner [7].

Weather

Standard English: "It’s raining outside."

AAVE: "It’s pourin’ out there, fam." – "Pourin’" intensifies the action, and "fam" (family) is a term of camaraderie [4].

Appalachian English: "Hit’s a-rainin’ cats and dogs." – "Hit’s" is a phonetic rendering of "it’s," and the idiom reflects regional flair [5].

Cockney: "It’s chuckin’ it down out there." – "Chuckin’ it down" is a vivid expression for heavy rain [6].

Scots: "It’s dreich ootside." – "Dreich" is a Scots word for dreary or wet weather [7].

Agreement

Standard English: "Yes, I agree."

AAVE: "Yeah, I’m with that." – "I’m with that" signals alignment or approval [4].

Appalachian English: "Yup, I reckon so." – "Reckon" means to think or consider, common in rural dialects [5].

Cockney: "Too right, I’m in." – "Too right" emphasizes agreement, and "I’m in" confirms participation [6].

Scots: "Aye, I’m wi’ ye." – "Aye" means yes, and "wi’ ye" translates to "with you" [7].

Time

Standard English: "What time is it?"

AAVE: "What’s the clock sayin’?" – A creative rephrasing of the standard query [4].

Appalachian English: "What time’s it gittin’ to be?" – "Gittin’ to be" reflects a regional syntactic pattern [5].

Cockney: "What’s the time on the old lemon?" – "Lemon" (from "lemon and lime," riming with "time") is Cockney rhyming slang [6].

Scots: "Whit time is’t?" – A concise Scots formulation with "is’t" blending "is it" [7].

Anger

Standard English: "I’m very angry."

AAVE: "I’m heated, yo." – "Heated" conveys intense emotion, and "yo" adds emphasis [4].

Appalachian English: "I’m plumb mad." – "Plumb" intensifies the adjective "mad" [5].

Cockney: "I’m proper narked." – "Proper" amplifies "narked," meaning annoyed [6].

Scots: "I’m fair scunnered." – "Scunnered" means fed up or irritated [7].

These examples underscore the creativity and adaptability of non-standard dialects. AAVE (Black English) often employs innovative syntax and borrowings from African linguistic traditions [4], while Appalachian English retains archaic forms from early British settlers [5].

Cockney is renowned for its riming slang and playful lexicon [6], and Scots blends English with Gaelic and Old English influences [7]. Despite their divergence from Standard English, these dialects are systematic and expressive, challenging the notion that they are "non-standard" in any absolute sense.

(Please note: Dr. Samuel Johnson introduced the form "rhyme" into English in the 18th century, mistakenly thinking that the term was a Greek derivative of "rythmos." Thus "rhyme" is an etymological error. For my explanation for using only the original form "rime," please see "Rime vs Rhyme: Dr. Samuel Johnson’s Error.")

The Importance of Standard English

While non-standard dialects enrich the linguistic landscape and preserve cultural heritage, the mastery of Standard English remains a critical skill in modern society.

Its rôle as a lingua franca facilitates communication across diverse regions and social groups, ensuring that individuals can participate fully in educational, professional, and civic spheres of society.

In academic settings, Standard English is the medium through which knowledge is disseminated and evaluated, enabling students to engage with global scholarship [8]. In the workplace, it is often a prerequisite for career advancement, as employers value the clarity and consistency it conveys [9].

Moreover, Standard English serves as a unifying force in multicultural nations, bridging linguistic divides that might otherwise hinder social cohesion [10]. The stigmatization of non-standard dialects can, however, marginalize their speakers, reinforcing social inequalities.

Linguists argue for a balanced approach: valuing dialectal diversity while equipping individuals with Standard English proficiency to navigate formal contexts. This dual competency empowers speakers to code-switch as needed, preserving their cultural identities while accessing opportunities afforded by Standard English.

Ultimately, learning Standard English is not about erasing dialects but about expanding linguistic repertoires to meet the demands of an interconnected world.

Standard English and non-standard dialects coexist as complementary facets of the English language, each serving distinct purposes.

Standard English provides a stable, widely recognized framework for formal interaction, while dialects offer vibrant expressions of identity and community, affording an interesting and colorful way of communicating.

The importance of learning Standard English lies in its capacity to open doors to education, employment, and global engagement, making it an indispensable tool for personal and societal advancement.

Sources

[1] David Crystal. The Stories of English. Overlook Press, 2004.

[2] Lynda Mugglestone. The Oxford History of English. Oxford University Press, 2006.

[3] Walt Wolfram and Natalie Schilling. American English: Dialects and Variation. Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing, 2006.

[4] John R. Rickford and Russell J. Rickford. Spoken Soul: The Story of Black English. New York: Wiley, 2000.

[5] Michael B. Montgomery. From Ulster to America: The Scotch-Irish Heritage of American English. Belfast: Ulster Historical Foundation, 2006.

[6] Jonathon Green. Cassell’s Dictionary of Slang. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2005.

[7] Billy Kay. Scots: The Mither Tongue. London : Grafton, 1988.

[8] Douglas Biber and Susan Conrad. Register, Genre, and Style. Cambridge University Press, 2009.

[9] Lesley Milroy and James Milroy. Authority in Language: Investigating Standard English. London and New York: Routledge,1999.

[10] Peter Trudgill. Sociolinguistics: An Introduction to Language and Society. London and New York: Penguin, 2000.

This content is accurate and true to the best of the author’s knowledge and is not meant to substitute for formal and individualized advice from a qualified professional.

© 2025 Linda Sue Grimes