William Butler Yeats’ "A Vision"

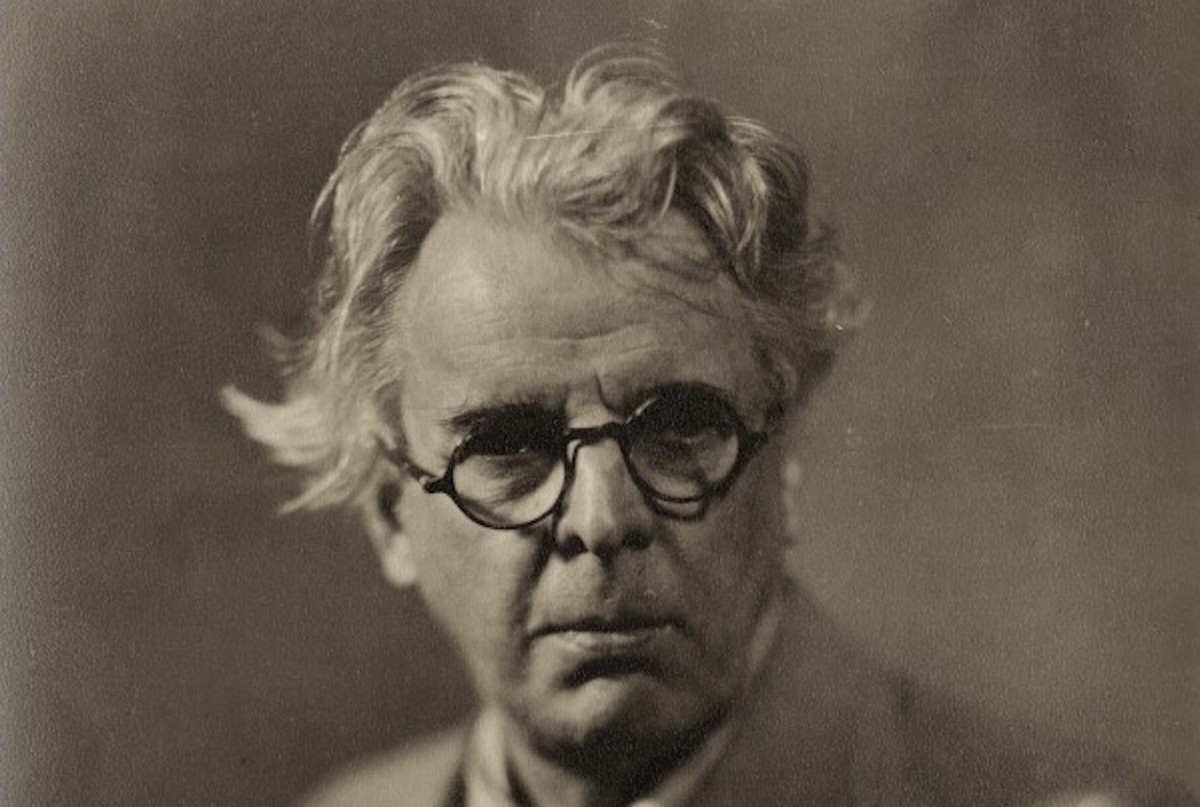

William Butler Yeats: A World-Class Poet

Many of William Butler Yeats' poems, including "The Second Coming" and "Sailing to Byzantium," reveal a profound sensitivity to the human condition, blending Irish myth with modern innovation.

Yet, beneath his celebrated poetry lies a less triumphant endeavor: A Vision, a sprawling metaphysical treatise first published in 1925 and revised in 1937. In A Vision, Yeats attempts to create a comprehensive system—a poetic ethic—that would unify history, personality, and art under a single rubric.

Despite Yeats’ stature as a world-class poet, A Vision represents a resounding failure. Far from establishing a coherent ethic, the work emerges as a cacophony of misguided notions, revealing Yeats’ superficial and often erroneous grasp of the Eastern religious traditions he claimed to have deeply studied.

Yeatsean Audacity

Yeats’ ambition in A Vision may be understood as the epitome of audacity. Supposedly inspired by automatic writing sessions with his wife, Georgie Hyde-Lees, beginning in 1917, the poet believed he had received revelations from spiritual "instructors" that offered a key to understanding human creativity as well as history.

The result was a system based on a cyclical theory of history, symbolized by interlocking gyres—conical spirals that represent the rise and fall of civilizations over 2,000-year periods. (For a discussion regarding the error of the gyres, please see "William Butler Yeats' 'The Second Coming'.")

Yeats divided human personalities into 28 phases of the moon, each corresponding to a specific type, and posited that art, history, and the soul were governed by these cosmic rhythms. His goal was not merely philosophical; he aimed to craft a poetic ethic, a lens through which his poetry could be both generated and then interpreted..

This ambition, however, was challenged by Yeats’ intellectual limitations. While his poetic genius thrived on intuition and ambiguity, the success of a work such as A Vision demanded precision and coherence—qualities it sorely lacks.

Scholars such as Richard Ellmann have noted that Yeats himself admitted to the work’s thinness and opacity, famously remarking in a letter to Ethel Mannin that he wrote it "to keep myself from going mad" [1].

The treatise’s reliance on occult sources, including theosophy and Rosicrucianism, already situates it on shaky ground, but its most glaring and distressing failure lies in Yeats’ mishandling of Eastern religious concepts, which he claimed as foundational influences.

An Eastern Mirage: Yeats’ "Romantic Misunderstanding"

T. S. Eliot labeled Western misunderstanding of Eastern philosophy and religious concepts "Romantic misunderstanding." He could have been pointing directly to Yeats in this evaluation.

Yeats’ engagement with Eastern religion was not a passing fancy. He was introduced to Hindu philosophy through his association with the Theosophical Society and his friendship with figures such as Sri Mohini Chatterjee, an Indian philosopher whom Yeats met in 1885.

Yeats' fascination deepened with readings of the Upanishads and the Bhagavad Gita, texts he revisited throughout his life.

In A Vision, Yeats explicitly invokes these traditions, particularly in his concepts of reincarnation, the eternal self, and the interplay of the pairs of opposites—ideas he aligns with his gyres and lunar phases.

Yet, a closer examination reveals that Yeats’ interpretations are not only idiosyncratic but fundamentally at odds with the traditions he sought to integrate.

Take, for instance, Yeats’ treatment of reincarnation. In Hindu and Buddhist frameworks, reincarnation (samsara) is a process governed by karma, the moral law of cause and effect, aimed at liberation (samadhi in Hinduism, nirvana in Buddhism, salvation in Christianity).

The Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, a key text Yeats references, describes the soul’s journey as a quest for union with Brahman, the universal consciousness or God (as that concept is understood in Western culture) [2].

Yeats, however, reimagines reincarnation as a mechanistic cycle tied to his gyres, devoid of moral progression or spiritual liberation. This watering down of the concept of reincarnation obliterates its deep, spiritual purpose in the lives of humanity.

His 28 phases of the moon assign fixed personality types—such as the "Hunchback" or the "Saint"—with no clear path to transcendence, reducing a dynamic process to a deterministic wheel.

Again, Yeats misunderstanding results in a fatal flaw that limits the Eastern concepts to mere thought experiments, not profound truths that guide individuals on spiritual paths to a definite goal.

Scholar Harold Bloom observes Yeats' limited awareness of Eastern religious concepts by suggesting that the poet's understanding of reincarnation amounts to little more than a parody; in Yeats system the soul is trapped rather than liberated [3].

Similarly, Yeats’ appropriation of the Bhagavad Gita’s concept of dharma (duty) is distorted beyond recognition. In the Gita, Krishna advises Arjuna to act according to his rôle as a warrior, emphasizing selfless action within a cosmic order [4].

Yeats, however, interprets dharma as a fatalistic submission to historical forces, as seen in his analysis of civilizations’ rise and fall.

His gyres suggest that human agency is illusory, a stark departure from the Gita’s call to active participation in one’s destiny. This misreading reflects not a deep study but a superficial cherry-picking of Eastern ideas to bolster his preconceived system.

A Cacophony of Contradictions

The intellectual incoherence of A Vision extends beyond its Eastern distortions to its internal structure. Yeats’ gyres, meant to symbolize the dialectical interplay of opposites (primary and antithetical tinctures, in his terminology), collapse under scrutiny.

He asserts that history oscillates between unity and multiplicity, yet his examples—such as the fall of Troy or the rise of Christianity—are cherry-picked and lack rigorous historical grounding.

Scholar Northrop Frye critiques this approach, arguing that the poet's historical cycles are poetic fictions masquerading as metaphysics, unsupported by evidence or logic [5].

The treatise’s reliance on vague assertions—for example the suggestion that the end of an age, which always receives the revelation of the character of the next age, is represented by the coming of one gyre to its place of greatest expansion [6]. Such bland unexplained statements further muddy the work's claims.

Moreover, the 28 lunar phases, intended as a typology of human character, devolve into arbitrary categorization. Yeats assigns historical figures like Shelley (Phase 17) and Napoleon (Phase 20) to these phases, but the criteria are inconsistent and subjective.

The system’s complexity overwhelms its usefulness, leaving readers with a tangled, labyrinthine taxonomy rather than a meaningful ethic. As critic T.R. Henn has avered that the work is less a philosophy than a privately concocted mythology, a wobbly scaffolding for Yeats’ imagination that collapses under its own weight [7].

The Poetic Ethic That Never Materialized

Yeats’ stated intention in formulating his treatise was to establish a poetic ethic, a poetic framework that would elevate his art and serve as a guide those who consume his art. Yet, A Vision fails to come together as either a practical guide or a philosophical statement.

Unlike Dante’s Divine Comedy, which integrates a clear Christian cosmology into its poetry, or Rabindranath Tagore's works that reveal the Eastern concepts as they are meant to be understood through a poetry that resonates with appropriate imagery as it reveals those concepts, A Vision remains detached from Yeats’ best poetry; its unhinged rhetoric is a like a raft let loose to the wind.

Poems such as "The Second Coming" draw loosely on its imagery—for example, the "widening gyre"—but their power lies in their ambiguity, not in the treatise’s labored explanations. Scholar Helen Vendler has suggested that Yeats’ great poems transcend A Vision, and that they succeed despite it, not because of it [8].

This disconnect underscores the work’s failure as an ethic. An ethic, poetic or otherwise, requires clarity and applicability—qualities A Vision sorely lacks. Its esoteric jargon and convoluted diagrams (the gyres, the wheel, the unicorn) alienate rather than enlighten, rendering it inaccessible.

Even the most devoted Yeatsean acolytes have struggled to reveal any logic or utility in the work.

Yeats’ Eastern borrowings, far from lending depth, expose his misunderstanding of traditions that emphasize simplicity and direct experience over intellectual abstraction.

The Zen Buddhist principle of direct insight, for instance, stands in stark contrast to Yeats’ overwrought theorizing, highlighting the huge gulf between his system and the philosophies he seemingly admired.

A Poet’s Folly

William Butler Yeats’ legacy as a poet is unassailable; his poetry remains a testimony to his genius. Yet, A Vision reveals the limits of that genius when applied to systematic thought.

Sadly, intended as a poetic ethic, the work instead emerges as a cacophony of wrong-headed ideas, its Eastern influences warped by misinterpretation and its structure undone by contradiction.

Yeats’ deep study of Hindu and Buddhist concepts, so proudly proclaimed, proves shallow in execution, a veneer of exoticism atop a fundamentally Western occult framework.

The treatise stands not as a triumph but as a cautionary tale: even a world-class poet can falter when straying too far from his craft. In the end, A Vision is less a vision than a mirage—a grand but misguided attempt to impose order on a world that resists such human intervention on a grand scale.

Sources

[1] Richard Ellmann. Yeats: The Man and the Masks. Macmillan. 1948.

[2] Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, trans. The Principal Upanishads. George Allen & Unwin. 1953.

[3] Harold Bloom. Yeats. Oxford University Press. 1970.

[4] Eknath Easwaran, trans. The Bhagavad Gita. Nilgiri Press. 1985.

[5] Northrop Frye. The Anatomy of Criticism. Princeton University Press. 1957.

[6] W.B. Yeats. A Vision. Macmillan. 1937.

[7] T.R. Henn. The Lonely Tower: Studies in the Poetry of W.B. Yeats. Methuen, 1950.

[8] Helen Vendler. Our Secret Discipline: Yeats and Lyric Form. Belknap Press. 2007.

Related W. B. Yeats Information

- Life Sketch of William Butler Yeats William Butler Yeats possessed a lifelong dedication to the cultural and political rebirth of Ireland. He experienced life as a poet, playwright, and senator as he lived during turbulent shifts in Irish politics. He had a lifelong unquenchable thirst for artistic and spiritual truth.

Commentaries on Other W. B. Yeats Poems

- William Butler Yeats' "The Indian upon God" William Butler Yeats’ poem "The Indian upon God" is displayed in ten riming couplets. The theme of the poem dramatizes the biblical concept that God made man in His own image.

- William Butler Yeats' "The Fisherman" In "The Fisherman," Yeats has created a speaker who is voicing a call for genuine art for the common folk, an art that dramatizes the beauty and truth inherent in all great art.

- William Butler Yeats' "Leda and the Swan" William Butler Yeats’ "Leda and the Swan" focuses on the ancient Greek myth, wherein the woman, Leda, wife of Tyndareus, was impregnated by the god Zeus in disguise as a swan. Yeats’ speaker is musing regarding the nature of such an act and how it might have impacted Leda's mental capacities afterward.

- William Butler Yeats' "Among School Children" "One of Yeats' most anthologized poems, tt features numerous allusions to ancient Greek mythology and philosophy. Yeats was always a thinker, even if not always a clear thinking one.

- William Butler Yeats' "The Second Coming" William Butler Yeats' "The Second Coming," is one of the most overrated and misunderstood works of the Western literary canon.

- William Butler Yeats' "Lapis Lazuli" In his poem "Lapis Lazuli," William Butler Yeats has his speaker explore the issue of peace and tranquility despite a chaotic environment.

This content is accurate and true to the best of the author’s knowledge and is not meant to substitute for formal and individualized advice from a qualified professional.

© 2025 Linda Sue Grimes