How To Renovate A Townhouse in Brooklyn Volume 1 Edition 2

The Walkthrough

Within hours of going into contract on a 112-year old townhouse in Brooklyn, Hubbie and I found ourselves beset with a whole new list of nerve-wracking questions, issues and dilemmas - aka The Loan Application. Since we wanted to buy a house in need of substantial work, we had applied for an FHA 203k loan that would allow us to borrow the funds to purchase and renovate our home in a single mortgage. 203k is a special mortgage product that allows qualified buyers to literally rescue distressed old houses, and without which many of New York City’s finest old homes could only be purchased by buyers paying cash.

That’s a lot of cash. But you’d be surprised how many buyers like that there seem to be in this town.

Not us. We have saved up enough for a 10% down payment and, as wage earners with solid work history, we will have to go through all of the proper channels, and jump through all of the necessary hoops, in order to buy this old house.

Among the endless items required by the bank for a 203k loan, is the obtainment of the services of a dedicated inspector. Unlike a regular home inspector who submits a report to the buyer citing the condition of everything from the roof to the plumbing systems, the 203k inspector has ultimate oversight concerning the scope, progress and ultimately, money, for your renovation project. The bank inspector is paid by you (it’s considered one of your closing costs) to tell your General Contractor what he or she can and cannot do and charge. And did I mention that the inspector controls your money?

Hubbie and I first got the phone number of our 203k inspector in 2009. At the time, we were in a race against another buyer to get an executed contract back to the selling attorney. The deal didn’t go our way (cash buyer) but I held onto the inspector’s number because something about him inspired confidence on the phone. Let’s call the inspector, Manu.

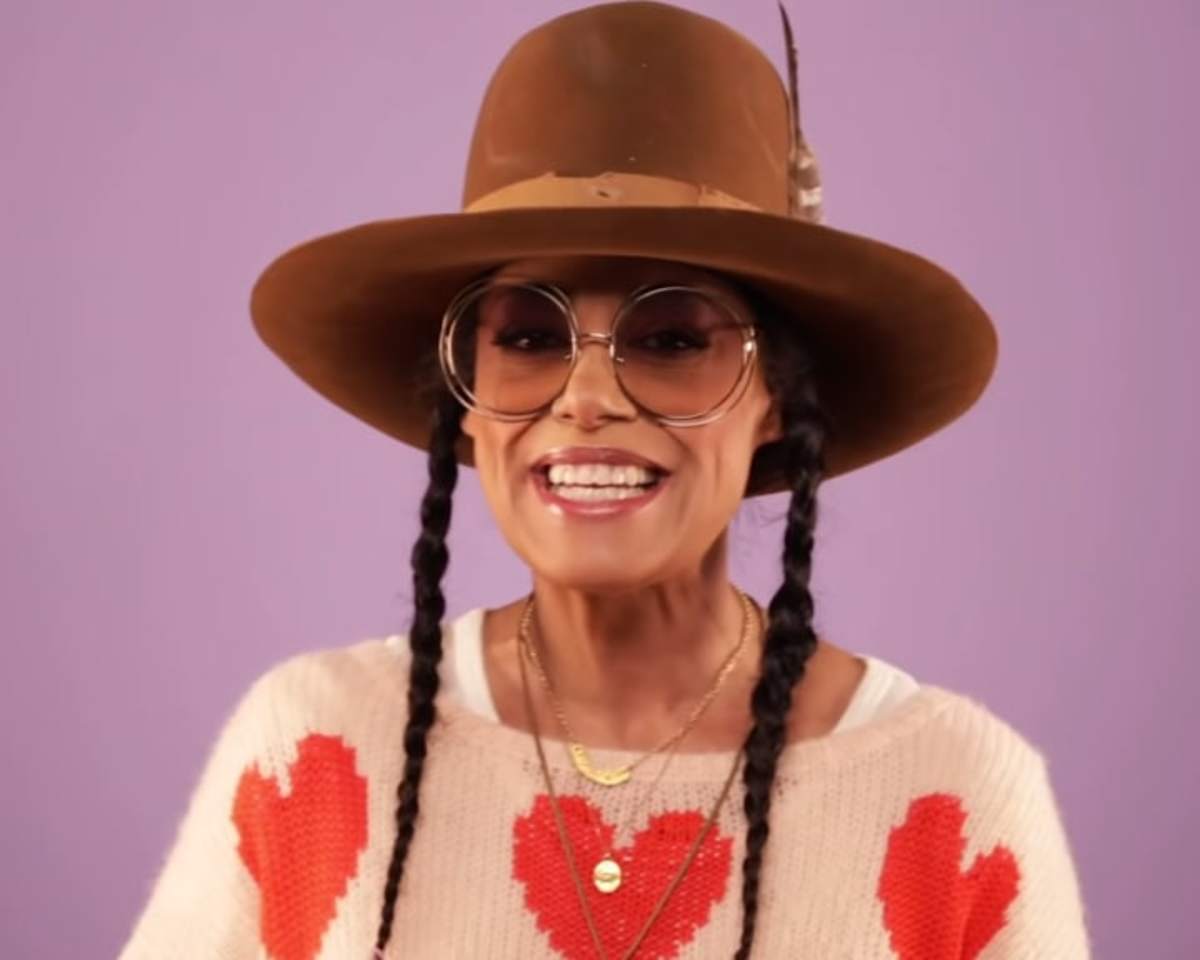

Two years later I arranged to meet Manu at the house in Brooklyn along with Hubbie and the sales agent, “Jane.” He had arrived 15 minutes early and was already talking to the agent, knocking on the plaster walls, and taking pictures with his digital Nikon camera.

“Sorry we’re late,” I apologized.

“No problem, Jane and I were just getting started.” Manu was already in charge. “So tell me what you want to do here.”

“As little as possible,” Hubbie offered.

We had discussed our plans over the preceding nights. The property is a 112-year old single-family house in a landmarked historic district. Unlike many old homes in New York City that have been converted into two-families, multi-families and even commercial properties, this single-family house is set up for us to renovate without having to change the official use. Our original plan had been to knock out as many walls as possible and to create the open floor plan that I miss so much from California. But ultimately we had decided to limit our scope of work to only what was required by the HUD to make the house livable and safe.

Sometimes a little really is a lot.

We started in the front walkway and garden where I learned what a tripping hazard is (New York City is full of them) and that the stairway and path would have to be redone for safety and aesthetics. We continued into the parlor where Hubbie and I explained out that we would keep the original moldings, columns and wainscoting, much of which had been painted white. We would leave the white paint too. It would be cheaper and faster than stripping and re-finishing everything.

The floors need a good deal of attention on both levels and additional money will have to be spent on matching the intricate pattern of the old parquet throughout. Meanwhile the walls and 10’ ceilings all appear to be in good shape. All the walls need is a skim coat, primer and fresh paint if you don’t consider that they might need to be tunneled through in order to install new electrical wiring.

“You guys are gonna have to get all new electrical wiring installed. With permits,” Manu insisted, taking a few swift clicks with his camera and jotting down some notes. “I’ll explain all of that in my report.”

Hubbie and I had already drafted our budget. We knew that the house needed an entirely new roof and that the bathrooms and kitchen would have to be gutted, re-plumbed, and completely re-installed with fixtures, appliances, tiling, cabinets and floors. Additional work in our scope included the installation of new exterior doors, all new plumbing and electrical, ductless A/C on both floors, washer-dryer in the basement, and the replacement of three of the home’s four original skylights.

In an effort to save money wherever we could, Hubbie and I had decided to keep the original four-bedroom floor plan intact. We would remove the wall at the top of the stairwell to create light throughout and had requested a cut-out in the kitchen wall until we could afford to have the wall removed and the header beams replaced. We know that the electrical system was old and sparsely arranged, but we had hoped to save significant money by going in, upgrading the defunct fuse box, and adding wiring for 110 or 220 volts as needed.

So much for that.

The electrical permits and upgrades would have to be added to our budget. Still, we had saved assiduously for several years, including Hubbie’s weekly deposits of a portion of his paycheck into a deposit box, so we had some room in our budget to maneuver just a little bit.

We continued through the kitchen and into the back yard. The chain link fence would need to be replaced but the neighbors’ yards were clean, tidy, quiet. Upstairs, Manu confirmed that we could salvage much of the original bathroom wall tile as well as fit in a double sink. Almost all of the home’s doors and windows are functional, simply needing cosmetic work and some hardware.

“No no. The house is in good shape,” Manu insisted when I showed hesitation about stepping into the downstairs bathroom. It has salmon pinks tiles and opens into the kitchen. We will move the bathroom door to the opposite wall and would like to install a claw foot tub with a shower riser and pedestal sink.

We left Brooklyn feeling reassured. Manu had given us a verbal estimate that was below our top number, even with the added electrical work. The bank requires a 10% -15% overage on the construction costs (depending on the bank) so we had just enough room in our pre-approval numbers to clear that required difference.

Things were really going our way.

Later, we got home and checked our emails. The bank processor had reached out to inquire about some documentation. Still riding on the confidence of our HUD inspection, I called the processor back right away.

“Your husband made a large deposit to his checking account in May,” she commented, “we need a letter explaining that.”

“Oh that’s easy,” I replied. I went on to explain that Hubbie cashes his paychecks every week and gives me $200-300 which I keep in a safe deposit box until we have enough money to make a significant deposit. Had the money sat in his checking account, Hubbie might have spent it.

“In that case, I can’t count the money towards your assets.”

“What?”

“It’s considered ‘cash on hand',” she continued, “and since we can’t trail it, we can't include it in your assets. But you should still be okay without it.”

It took me a few days to admit to Hubbie that my savings scheme had been a total bust - that the funds he had worked so hard to earn and save would be “backed out” of our asset calculation by the bank. But by then, we had a whole new set or concerns, issues and problems to focus on and fret over-aka The General Contractor.