How to make lumber from your woodlot for use in your home

For many years, I have been thinning my woodlot on my 12 acres in upstate New York. The forest is a result of the abandonment of a pasture in 1960, so the density of trees is quite high. This is a perfect time to remove a percentage of those trees to allow the remaining individuals to grow tall and fast. I have used the wood obtained in this process to heat our house, using a wood-burning stove located in the basement. But a few years ago, I realized that some of the trees I decided to remove were larger than normal ( more than 16 inches in diameter) and could probably be used for lumber rather than firewood.

Learn to do woodworking

Cutting the logs

So I found a guy in town who has a portable sawmill who will come to your home and cut up logs for lumber. Dierk has been doing this for many years. He will also cut the trees if you don’t do that kind of thing yourself. He used to use a horse to drag the logs from the forest, but now he uses a tractor. I cut my own logs and leave them in the woods for him to assemble at his portable sawmill that he sets up in my driveway. Logs are cut 8 ½ feet long, or I leave the log in the woods at some multiple of this length. Carpenters like to have a good 8-foot board with which to start, so cut them about 6 inches longer to allow for waste.

Dierk places each log in turn on the table of his sawmill, and then the moving saw slices off boards at any desired thickness. He operates the machinery while I remove each board for stacking. The process goes faster with two people. Initially, slabs of the exterior wood with bark are removed, which I stack in the woods and use later for bonfires. After the exterior slabs are removed, you are left with a square log that is ready to slice. I like rough-cut boards 1 ¼ inch thick to give my carpenter plenty of wood to work. Your carpenter has to run the boards through a planer and jointer to produce a flat, smooth piece of wood and, again, there is abundant waste produced in this process. A 1 ¼ inch thick board results in a finished piece of wood about ¾ or 7/8 inch thick after milling. I have had Dierk cut boards at 1 1/8 and at 1 ¼ inch thick, and I prefer the latter. The cutting on the portable mill also produces a great deal of sawdust, which you can use in your compost pile or as mulch.

Sticker and stack

Once cut, the lumber needs to be properly stacked so it can dry. The drying process is absolutely critical, because moist wood will shrink later after construction leaving cracks in your finished product. No reputable carpenter would use wood that is not dry enough anyway. In my case, I stack the wood initially in my garage, using a system called “sticker and stack”. The wood is stacked neatly in layers, which are separated by 1x1 inch “stickers”. I stack wood in a pile that is about 8 ½ feet by 6 feet, and I use 5 stickers evenly spaced between each layer of lumber. You also leave 1-2 inches of space between each board within a layer. The stickers and the spacing are essential to allow air circulation throughout the pile to facilitate drying. I usually cut in the spring, stack the wood in my garage until fall, which allows for initial drying, and then move the wood to my basement to complete the drying process. Because we heat our home with wood using a wood stove in the basement, that space is the driest area in the house. I restack the wood a few yards from the stove, which requires moving the entire pile that was in the garage, and let it remain there until spring. By that time, the wood is completely dry and ready to work.

Dierk cuts up a couple of logs of aspen for me to create abundant stickers for use in the stacking process. Aspen is the least valuable species I cut, so we use it for stickers, which can be used over and over again through the years. Fresh stickers contain water also and will leave a “sticker stain” on the boards resting on them, but this is no big deal. Most of that stain is removed in milling. Some stain might remain on the finished board, but I actually think this gives the board more character. Once the stickers themselves are dry, this is not an issue the next time you use them.

The cost

You can also take the rough-cut lumber to a kiln where they will dry the wood for you in less time than my process takes. However, you have to transport the wood there and pay for the drying; in fact, kilns near my home were not interested in taking my wood for drying because the quantity was so small. They mostly dry an entire house’s worth of wood for commercial construction and they did not want to deal with my puny amount. Both times I have had lumber cut from my woodlot, it has produced about 1,000 board feet of lumber. A board foot is equal to a square board 1 inch thick, and 1 foot x 1 foot in length and width.

Dierk charges about $1 per finished board foot of lumber for the entire process. There is an additional charge if he cuts down the trees at the start. So, I get 1,000 board feet of rough-cut lumber for about $1,000. I also contribute substantial work by cutting trees and stacking lumber. This is certainly less expensive than buying finished wood from the lumberyard, and the pride of seeing wood you cut on your own property inside your home is priceless.

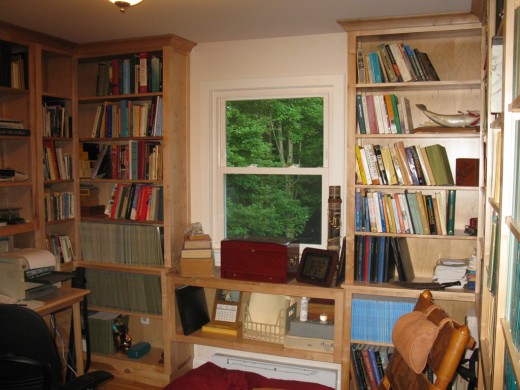

Finished product

My den/library was the first project for which I hired my carpenter. He used red maple for that, and we will remodel our kitchen using the same species. Aspen is perfect for trim around windows and doors, and for baseboards, because it takes paint well. White ash was used to make several interior doors to replace the hollow core doors originally used throughout. I also cut some American elm and black cherry, but I am not sure how I will use them yet. In general, we are adding substantial wood to the interior of the house, grown on our land, selected and cut by me, practical in the short run, and admired for generations to come.