Rain Water Harvesting—Alternative Water Supply

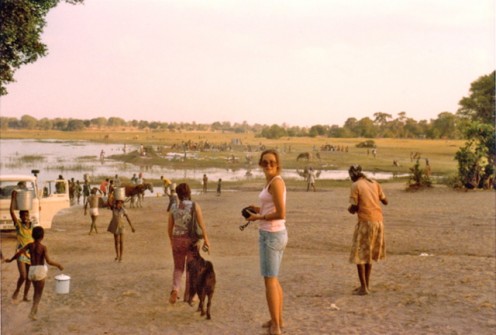

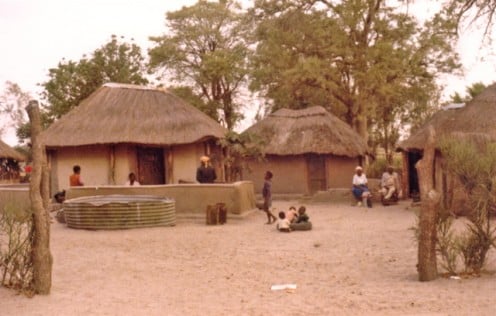

When I was a Peace Corps volunteer in Botswana, I lived in a grass-thatched mud hut for six months near the edge of the village of Maun. I used to watch women and girls carrying buckets on their heads to the river to collect water. The full buckets were heavy, so they wore wound-up cloths on their heads for padding. Often the water was dirty - clothes and bodies were washed in the same river spot. I worried about disease.

Now I wonder if they could have channelled rainwater into an underground storage space, instead of going to the river every day. They could have had their own clean supply right inside each compound, specifically for drinking and cooking.

Stable Water Supply

In Hawaii, where rain falls regularly, there are people who don't get enough water. In Southern California, where it's dry, the same is true. Although the state and water utilities work hard to supply as much water as they can, there's no money anymore to pay for the types of mega-projects they used to install. We need to start thinking smaller.

Imagine a new housing community built to capture and utilize rain right there - a giant cistern under a park or community garden right in the middle of all the housing. Each house would capture and purify water from their own roof for house needs. No need for supply from somewhere else.

This is what we need now. Small projects attached to each house as it's built, with maintenance instructions left for the new homeowner, and community water supply for community vegetation.

Mega-projects like we're used to are usually built for agriculture or manufacturing, while communities get the dregs. They also destabilize the environment and sometimes destroy the very thing we seek - a stable water supply.

Water Supply in Southern California

Southern California provides an excellent example of mega-projects gone awry over the years. SoCal is made up of giant aquifers that once were filled with water. Anytime you punched a hole in the ground west of the mountains or in valleys between, water would spurt up. The ground was open to rain, fairly flat and subject to flooding, but by nature absorbable - like a giant sponge. There was no lack, except in a few areas (like San Fernando).

San Francisco Delta

Over time, however, growing cities paved the ground over and redirected rainfall to the oceans, through storm drains, to prevent floods. People swarmed to California's sunny beaches from all over the country and then the world. Rain, no longer having access to the aquifer, could not refill it and water became scarce.

Water companies built long aqueducts to transport water from the Owens Valley, the Colorado River, and finally from the San Francisco Delta in Northern California. All of these projects were immensely costly. Adding to the cost, water was (and still is) lost through evaporation as it travelled that long distance, and massive amounts of electricity were used to move water up hills and across flat country. (The biggest use of electricity in California is for water supply.) What these projects did was to make it possible for more and more people to migrate, so more and more water was needed.

Now the main supplier, the San Francisco Delta, is losing its health. Fish are dying out, water is becoming polluted and salty, birds are moving away. The country's 2nd largest remaining estuary is falling apart. Strangely, the state of California is talking about building two new tunnels to direct even more water from the delta to the south.

Southern California's water supply system is no longer working. We need a new one. And technology is giving it to us.

New Water Technology

Engineers, architects, and manufacturers have responded to the water supply crisis by developing new water technologies, designs, and products. Some help people to use less water, some help clean waste water for reuse, and others help increase supply.

On the supply side, many people have noticed the wastage of rain water. It hasn't slipped by that people used to collect their own water in the old days (and still do in Southeast Asia) before centralized water systems were developed. Manufacturers responded and here are new technologies related to capturing and storing rain - the type of technology that countries like Botswana could directly benefit from and may outpace Westerners in implementing.

Rain Collecting Roofs

Some types of new construction are contouring their roofs to make it easier for rain to run off in a controlled manner. Earthship construction, for example, has roofs shaped to automatically feed water into a downspout leading directly to an underground cistern. On the way down, the water is filtered through a rock/soil combination that takes out impurities.

The cistern feeds the house with its entire water supply, even in dry locations like New Mexico. Water from the cistern is fed through purification filters inside the house to be made potable, and all water is reused in some way until there is none left to use.

[If you are considering this for your house, note that certain types of roofs are not suitable for harvesting rainwater. If you have a cedar shake or asbestos roof, don't consider it - both are toxic. If you have a composite roof, check to see if it includes toxic materials. Asphalt, for example, is petroleum based and therefore toxic. Also check your roof for zinc or copper added to prevent moss. Rainwater will pick up enough of it to become toxic to your landscape too. Roofs with moss growing on it are ok.]

Roof Gardens

Green roofs are gardens planted on the roofs of buildings to help cool the building and also collect rainwater. This is another practice that is actually ages old, but that Westerners have now developed stronger roof structures to support. The City of Chicago was the first public structure in the United States to openly endorse and construct a roof garden. Others have followed suit.

A roof garden consists of a waterproof membrane spread across a strong, flat roof, on top of which is a tough, root resistant fabric, a water-storing drainage layer, another protection fabric, a layer of lightweight, specially constructed soil, and finally plants. A roof garden retains 1/2 to 3/4 of the rain that falls upon it. It also saves energy. It is possible to grow crops on a roof garden and it's also possible to grow grass. UC Berkeley in California has a soccer field planted on top of one of its parking garages.

Bioswales & Rain Gardens

Since roof water, in most cases, will be used primarily for irrigation, why not go direct and create a built-in hollow in your landscape to collect water when it rains? Nature does it everywhere.

Instead of running off into storm drains, water will have the time in a depression to sink down into the soil. This is called a bioswale . . . unless you plant water-loving plants in or around it to make it more attractive. Then it's called a rain garden.

The importance of this type of rain collection cannot be overstated. If you want to see how much water can be retained with this method, as compared with rain barrels and cisterns, watch the video below.

Parts of a Rain Collection System

Rain Barrels and Cisterns

Rain barrels and cisterns are containers that store rain collected from the roof of a building. They are made in different sizes to give you plenty of options.

Rain is supplied to both in the same way - via downspouts and a filter that diverts the first few gallons of dirty water to the side as the roof is cleaned, then directs water from the newly cleaned roof into the container for storage.

Rain barrels generally store 55-75 gallons of water. They sit up against your house under a water spout you insert to direct the water down from the roof gutter. They have a screen on top to filter out debris and keep mosquitoes from getting inside.

Many styles are made to hook together - you can string a whole set of them along a wall, if one is not enough. Some rain barrels can be painted to match the color of your house, and there are some with containers on top that let them be used as decorative planters.

Cisterns are larger containers (up to 50,000 gallons for fiberglass) that are generally buried under the ground, with water being pumped to the surface when needed. They have long been common components of dwellings around the world, some dating as far back as 8,000 years BC. In agricultural areas, cisterns are often raised above the ground on a platform to allow for distribution using gravity, instead of a pump. There is also a newer type of cistern known as a rain pillow that has soft sides that swell up when filled with rain. That kind lies flat and can be hidden under a raised deck.

Although most of the talk about these systems centers around using roof-collected water for irrigation only, it doesn't have to be that way. You can pump the water into the house and through a purification system for drinking and other uses.

Calculations for Feasibility

Will rainwater harvesting net you enough water to make it worthwhile? You will need to do a little calculating to see, matching water use with potential water supply. Here are some general figures to go by:

Water Use: Unless you have installed a native garden - in which case you shouldn't need much irrigation water at all - you can estimate that irrigation takes up about 60% of your water bill. This will be lower or higher, depending on how many people live in your house. Calculate what you need per year for irrigation, then look at potential supply.

Supply: if you have a 1,000 sq ft. roof (a small, two-bedroom house) you could expect to retain about 6,200 gallons of rain in an area that receives 10" of rain per year, according to the chart in Georgia's Guidelines for Rainwater Harvesting (linked below, pg. 25). How does that amount compare with your landscape's needs?

Cost: Using your calculations above, you can estimate the costs with the following chart. Figure out how often it rains in your area. If it rains often, but the amount you need per rainfall is 160 gallons, consider setting up a string of three barrels, each connected to the other. That will give you 180 gallons, which should be plenty. If your area is really dry, you may need an underground cistern. Perhaps you could go in with your neighbor to get one for both of you. Check with your local water supplier, also, to see if they offer rebates.

Note: These costs do not include installation.

Item

| Size

| Estimated Cost

|

|---|---|---|

Rain barrel

| 60 gallons

| $160

|

Small, above ground cistern

| 650 gallon

| $1,100-1,200

|

Large, underground cistern

| 10,000 gallons or bigger

| $5,000-8,000

|

For more information about rainwater systems:

- Rainwater Harvesting Guidelines | State of Georgia

Includes charts that show how to calculate runoff volume from your roof. - Green Roofs: Best Management Practices | City of Chicago

Green roofs are layers of living vegetation installed on top of buildings, from small garages to large industrial structures. They have multiple benefits, as described here. - Beyond Green Roofs: 15 Vertically Vegetated Buildings | WebEcoist

Some buildings are installing gardens going up the outside walls.