Amazing Carnivorous Plants: Nature’s Bug-Eating Wonders.

Carnivorous plants are fun and fascinating

Carnivorous plants are fun and fascinating because they combine science, nature, and a bit of mystery into living “traps” that capture and digest insects. Their unique feeding habits make them exciting to watch, sparking curiosity and wonder—especially for kids who love hands-on learning and exploring the natural world. Growing carnivorous plants can be a rewarding project that teaches responsibility, biology, and ecology. Plus, their unusual appearance and impressive hunting tricks make them fantastic conversation starters, captivating guests and turning any space into a mini botanical adventure. Whether used in classrooms, homes, or science fairs, carnivorous plants bring excitement and education together in a truly memorable way.

A Venus Flytrap having a snack

The Venus Flytrap

The Venus Flytrap (Dionaea muscipula) is easily the rockstar of the carnivorous plant world. Famous for its jaw-dropping ability to snap shut on unsuspecting insects, this remarkable plant has captured the imagination of scientists, gardeners, and curious minds alike. Native exclusively to the swampy, nutrient-poor wetlands of North and South Carolina, the Venus Flytrap has evolved an ingenious survival strategy that’s equal parts elegant and ruthless.

At first glance, the Venus Flytrap looks like a collection of ordinary green leaves, but a closer look reveals a natural marvel. The key to its hunting success lies in the unique structure of its leaf-blades, also called laminae. Each leaf ends in a pair of hinged lobes, which resemble a set of open jaws lined with stiff, hair-like teeth. These “teeth” are not for chewing but for locking the trap tightly shut, preventing the captured prey from escaping.

What really sets the Venus Flytrap apart are its “trigger hairs.” Each trap sports between two and six tiny, sensitive hairs inside the lobes. When an unsuspecting insect brushes against these hairs—usually more than once in quick succession—the trap springs into action, snapping shut with surprising speed. This movement happens in less than a second, one of the fastest motions in the plant kingdom. It’s like a high-tech vault closing, designed to trap and imprison its prey instantly.

Once closed, the trap seals tightly to form a kind of stomach, where the plant releases digestive enzymes that break down the soft tissues of the insect. Over the course of about five to twelve days, the Venus Flytrap absorbs essential nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus, which are scarce in its natural habitat’s soil. After the nutrients are extracted, the trap reopens, ready for its next catch.

Growing a Venus Flytrap is a rewarding challenge, but it requires mimicking the plant’s natural environment. These plants thrive best with at least four hours of direct sunlight daily, moist but well-draining soil, and high humidity. In the wild, they grow in acidic, nutrient-poor bogs, so it’s important to use the right kind of soil, such as a mixture of peat moss and sand, and avoid fertilizers which can harm the plant.

For those who keep Venus Flytraps indoors, feeding them is part of the fun. The plant typically catches small live insects like flies or spiders about once a week. If you don’t have a ready supply of bugs buzzing around your home, you can feed the plant small insects occasionally. Just be sure to feed live prey to trigger the trap’s closing mechanism; dead bugs won’t stimulate it. Watching the trap snap shut on its next meal is thrilling—a moment of pure nature-meets-mechanism that never loses its wow factor.

The Venus Flytrap’s fascinating hunting strategy, combined with its unusual appearance and exclusivity to a small part of the world, has made it a symbol of nature’s ingenuity and the unexpected ways life adapts. From swampy marshes to your windowsill, the Venus Flytrap continues to captivate and inspire anyone lucky enough to witness its captivating snap.

Pitcher Plant

The Pitcher Plant

Look at these crazy-ass plants! It looks like a beautiful jug or chalice. Deceptive in its beauty these things devour other lives!

Inside the beautiful vase-like structure are digestive juices that this plant uses to melt and devour its breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

Pitcher plants are some of the most unusual members of the plant kingdom. Belonging to several different genera—such as Sarracenia (native to North America), Nepenthes (primarily tropical Asia), and Darlingtonia (the cobra lily, found in the western United States)—pitcher plants share a fascinating carnivorous adaptation that sets them apart from most other plants. Their unique method of capturing and digesting insects has intrigued botanists, gardeners, and nature enthusiasts alike.

At its core, a pitcher plant is a carnivorous plant that traps prey inside a deep cavity filled with digestive fluid. This “pitcher” is a modified leaf—an ingenious evolutionary adaptation that allows the plant to thrive in nutrient-poor environments such as bogs, wetlands, and acidic soils where nitrogen and other vital nutrients are scarce.

The modified leaf forms a tubular or funnel-shaped structure that acts as both a lure and a trap. The inside of the pitcher is slippery and often coated with nectar or other attractants. Insects and other small creatures, attracted by the scent or the promise of nectar, land on the rim of the pitcher—called the peristome—and often slip into the cavity below, unable to escape due to the smooth, waxy inner walls.

Pitcher plants exhibit remarkable structural diversity, depending on the genus and species. For example, Sarracenia species, commonly called North American pitcher plants, have upright tubular leaves with a flared opening, often topped by a hood-like structure that prevents rainwater from diluting the digestive fluids. These hoods are sometimes brightly colored or patterned, helping to attract prey.

Tropical pitcher plants in the genus Nepenthes produce larger, hanging pitchers that can be several inches long and sometimes large enough to trap small vertebrates like frogs or rodents. These pitchers often feature a prominent lid that prevents excess rain from filling the trap and diluting the digestive enzymes inside.

The inner surfaces of the pitcher are equipped with downward-pointing hairs or a waxy coating that make climbing out nearly impossible. Once trapped, the insect drowns in the digestive liquid, where enzymes break down its body, releasing nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus, which the plant absorbs to supplement its growth.

Pitcher plants have evolved to thrive in challenging habitats where other plants struggle to survive. Many species grow in bogs, marshes, or acidic wetlands where the soil is deficient in essential nutrients. Instead of relying solely on root absorption for nutrients, pitcher plants supplement their diet by capturing and digesting insects and other small organisms.

This carnivorous adaptation gives them a competitive advantage in environments where nitrogen is limited. The nutrients obtained from prey help the plants grow, flower, and reproduce more successfully than they otherwise would.

The feeding process of a pitcher plant is a remarkable example of evolutionary ingenuity. The rim of the pitcher, or peristome, secretes nectar to lure insects. Some species emit specific scents that mimic decaying organic matter or flowers, depending on the prey they seek.

Once an insect lands on the rim, it often encounters a surface so slippery that it loses footing and tumbles into the trap below. Inside, the insect struggles against the waxy walls and downward-pointing hairs that prevent escape. Eventually, it succumbs to exhaustion or drowns in the fluid.

Digestive enzymes and symbiotic bacteria break down the insect’s soft tissues, releasing nutrients into the fluid. The plant then absorbs these nutrients through specialized cells lining the pitcher.

Pitcher plants are not only fascinating for their carnivorous habits but also for their role in their ecosystems. They provide microhabitats for various organisms, including mosquito larvae, certain species of ants, and even some frogs that have adapted to live within the pitchers, benefiting from the environment without being digested.

This mutualistic relationship helps keep the pitcher clean and may assist in breaking down prey more efficiently. Additionally, the presence of pitcher plants contributes to biodiversity in wetlands and bogs, supporting complex food webs.

Pitcher plants are popular among carnivorous plant enthusiasts due to their unique appearance and captivating feeding behavior. Cultivating them requires replicating their natural environment as much as possible.

Most pitcher plants prefer acidic, nutrient-poor soil, often composed of sphagnum moss, sand, or peat. They need plenty of sunlight—many species thrive with at least four to six hours of direct sunlight daily—and consistently moist conditions without standing water.

In cultivation, pitcher plants can be fed live insects or diluted fertilizer designed for carnivorous plants, though they generally capture enough prey on their own when grown outdoors.

Many species of pitcher plants are threatened by habitat destruction, pollution, and climate change. Wetlands, bogs, and other nutrient-poor habitats are often drained or altered for agriculture and development, reducing the available habitat for these specialized plants.

Conservation efforts focus on protecting native habitats, cultivating pitcher plants in botanical gardens, and educating the public about the importance of preserving these unique species.

Pitcher plants are extraordinary examples of nature’s creativity and adaptability. Through their specialized pitcher-shaped leaves, they have transformed from simple plants into skilled hunters, capturing and digesting insects to thrive in environments where nutrients are scarce. Whether admired for their striking appearance, their ecological significance, or their evolutionary marvel, pitcher plants continue to captivate and inspire those who study and care for them.

The Waterwheel Plant

Waterwheel Plant

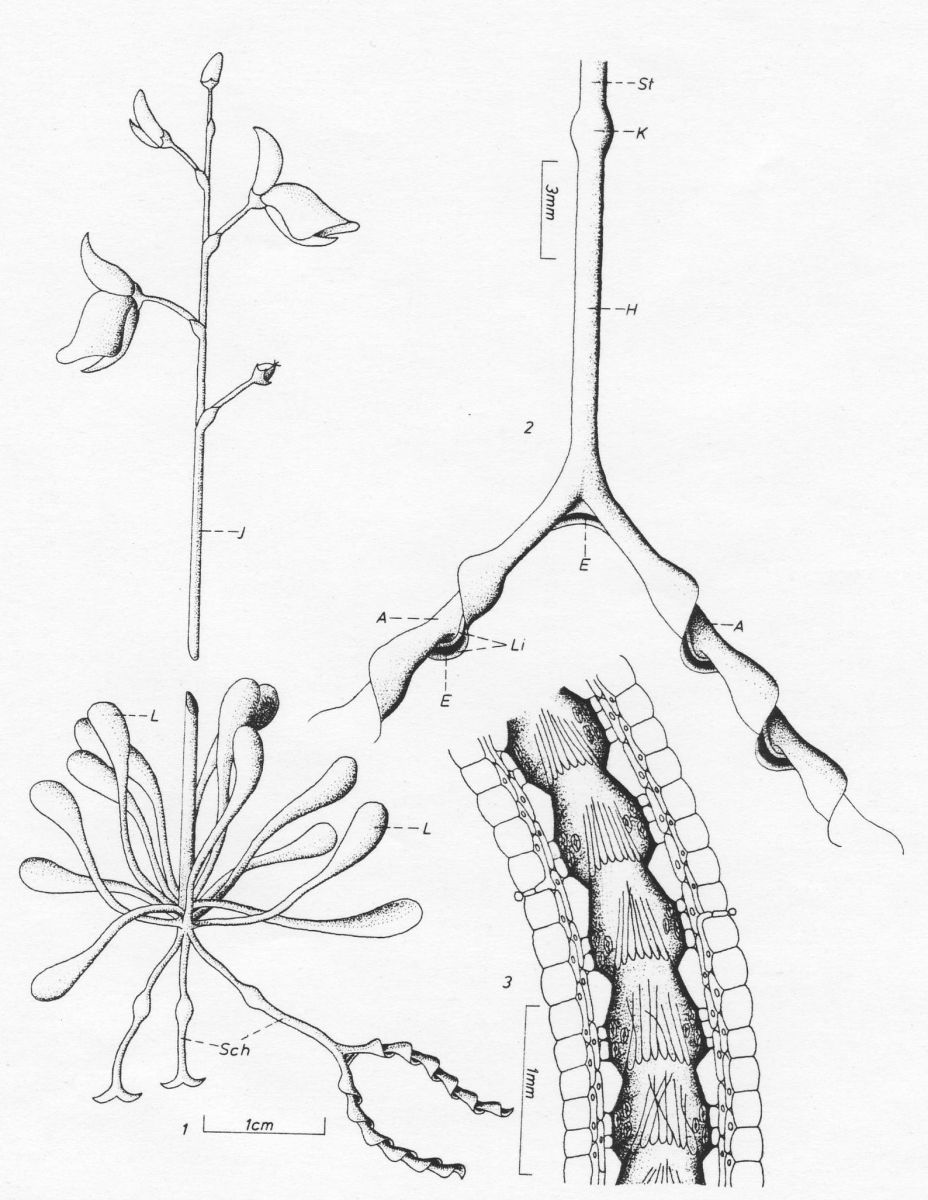

The Waterwheel Plant (Aldrovanda vesiculosa) is one of the most remarkable and rare aquatic carnivorous plants in the world. Closely related to the famous Venus flytrap (Dionaea muscipula), it shares the same snap-trap mechanism but lives entirely submerged in water. This unique plant combines beauty, complexity, and evolutionary ingenuity, thriving in nutrient-poor freshwater habitats where it supplements its diet by capturing small aquatic animals.

The Waterwheel Plant is a free-floating, rootless aquatic plant that typically grows in shallow, nutrient-poor lakes, ponds, and slow-moving streams. Unlike many aquatic plants, it lacks roots entirely and instead floats freely beneath the water surface, anchored only by its stem and whorls of tiny, specialized leaves.

The plant gets its name from the circular arrangement of its leaves around the stem, resembling the spokes of a waterwheel. These whorls occur in groups of 6 to 9 leaves, each measuring just a few millimeters long. Each leaf functions as a small trap, equipped with a highly specialized snap mechanism similar to that of its terrestrial relative, the Venus flytrap.

The Waterwheel Plant’s carnivorous adaptation is truly astonishing. Each leaf has two hinged lobes with trigger hairs on their inner surfaces. When a small aquatic creature, such as a water flea or tiny crustacean, touches these hairs, the lobes snap shut in less than a tenth of a second, trapping the prey inside. This rapid movement is one of the fastest in the plant kingdom and relies on changes in cell turgor pressure to power the closing action.

Once the prey is trapped, the plant secretes digestive enzymes to break down the soft tissues, allowing it to absorb essential nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus. This adaptation enables the Waterwheel Plant to thrive in habitats where the water is low in nutrients, which would otherwise limit plant growth.

The Waterwheel Plant is native to Europe, Asia, Africa, and Australia, but it has a very patchy and scattered distribution due to its specific habitat requirements. It prefers clean, still or slow-moving freshwater bodies that are acidic or slightly alkaline and rich in organic material but poor in nutrients.

Because of habitat loss, pollution, and changes in water management, many populations of Aldrovanda vesiculosa have declined dramatically, leading to its status as a vulnerable species in several regions. Conservation efforts focus on protecting wetlands and restoring suitable aquatic environments to preserve this extraordinary species.

The Waterwheel Plant grows by extending its slender, branching stems, which can reach lengths of up to 20 centimeters or more. As it grows, new whorls of snap-trap leaves form along the stem, creating the characteristic “wheel” shape.

Reproduction occurs both sexually and vegetatively. The plant produces small, inconspicuous flowers that emerge above the water surface during the summer. These flowers are self-pollinating or cross-pollinated by insects. However, much of its propagation is through fragmentation, where pieces of the stem break off and develop into new plants, allowing rapid colonization of suitable habitats.

The Waterwheel Plant plays an important role in freshwater ecosystems by controlling populations of small aquatic invertebrates. Its carnivorous nature allows it to gain nutrients in environments where others struggle to survive.

For botanists, aquarists, and nature enthusiasts, Aldrovanda vesiculosa represents a captivating example of evolutionary innovation. Its delicate beauty combined with its fast, precise hunting mechanism makes it a prized species in carnivorous plant collections and a subject of ongoing scientific study.

Bladderwort

Bladderworts

Meet the bladderwort (Utricularia), the plant world’s little carnivorous vacuum cleaner. This aquatic or semi-aquatic marvel is basically a tiny, underwater bug-sucking ninja that doesn’t need roots, soil, or even much sunlight to thrive. Instead, it hangs out in ponds, lakes, and marshes, waiting to suck up unsuspecting prey with its high-speed bladder traps.

So, how does it work? Picture a miniature balloon with a trapdoor—this is the bladder. When a tiny water critter brushes against the sensitive hairs near the bladder’s entrance, the trapdoor snaps open faster than you can say “gulp,” sucking the poor bug inside with a vacuum-powered slurp. The trapdoor then snaps shut like a trapdoor on a cartoon villain’s lair, and the bladderwort gets busy digesting its catch. Talk about efficiency!

What’s wild is how bladderworts don’t bother with the whole “roots and soil” routine. Some species float freely in the water, while others anchor themselves in muddy bottoms—either way, they’re the ultimate low-maintenance carnivores. No need for fertilizer or watering—just bugs and a splash of water.

Bladderworts come in all shapes and sizes, with some looking like feathery underwater ferns and others producing tiny, snapdragon-like flowers above water that say, “Hey, I’m fancy too!”

If plants had a version of a party trick, bladderwort’s would be vacuuming up dinner in less than a millisecond. It’s nature’s tiny, stealthy predator—quiet, efficient, and surprisingly fun to watch if you have a microscope handy.

So next time you’re by a pond, remember: lurking beneath the surface is a plant with a secret weapon, ready to suck in dinner faster than you can blink!

Butterwort

Butterworts

The butterwort (Pinguicula), the plant that’s basically nature’s version of flypaper—only way fancier and way more charming. This carnivorous wonder doesn’t just sit there looking pretty; it’s out there on a mission to snack on bugs, and it does it with style.

First off, don’t let the name fool you. Butterwort isn’t some delicious dairy product—though you might want to avoid licking it. The name actually comes from its shiny, greasy-looking leaves that look like they’ve been slathered with butter. These leaves aren’t just for show; they’re sticky, glandular traps designed to catch unsuspecting insects who think they’ve landed on a lovely snack spot, only to find themselves glued in place like they just got VIP tickets to the “No Escape” concert.

The secret sauce? Tiny glands on the leaf surface secrete a gluey mucilage that’s both sticky enough to trap bugs and loaded with digestive enzymes to break them down. So, the butterwort doesn’t just hold on to its prey—it slowly digests it like a chef simmering a delicious broth, absorbing nutrients that are hard to find in the poor soils where it usually lives.

Butterworts prefer shady, damp environments like bogs, rocky cliffs, or mossy forest floors—basically places where most plants have to tough it out. But butterworts? They say, “Bring on the bugs!” and get to work. Their leaves are often a luscious green or even a vibrant purple, making them look like the drama queens of the plant world.

What’s also cool—and kind of hilarious—is that butterwort flowers can be downright showy. They come in all sorts of colors, from soft pinks to bright purples and yellows, and look like they’re dressed for a fancy garden party. Meanwhile, the leaves below are busy being sticky little assassins.

If you want to grow a butterwort at home, be prepared: you’ll need to keep its soil moist but not soggy, and feed it the occasional bug (or let it catch its own). And if you don’t have bugs handy, well, it might give you the side-eye—because let’s be honest, it’s a bit of a picky eater.

In short, the butterwort is the perfect mix of beauty and beast. It’s a bit like that friend who looks sweet and innocent but actually has a mischievous streak—and a pretty impressive appetite for bugs. So next time you spot one, give it a nod of respect—it’s working hard to keep its dinner stuck where it wants it!

Sundew

Sundews

In the hidden realms where mist lingers and shadows dance beneath ancient trees, there thrives a creature of delicate beauty and quiet power—the sundew. Known to the mystics as Drosera, this plant is far more than a mere member of the botanical world. It is a whisper from the earth’s secret heart, a living spell woven of dew and sunlight, a silent hunter cloaked in glittering jewels of liquid crystal.

Imagine wandering through a twilight bog, where the air is thick with the scent of moss and rain-soaked earth. There, catching the fading light, the sundew reveals itself: a small rosette of tender, glistening leaves, each adorned with hair-like tendrils crowned by droplets that shimmer like drops of enchanted morning dew. These droplets are no ordinary water—they are a sticky elixir, a lure crafted by nature’s alchemists, shimmering like diamonds to tempt the unwary traveler of the insect realm.

But do not be fooled by the sundew’s ethereal beauty. Beneath this sparkling facade lies a cunning predator, a sorcerer of survival in the wilds where nutrients hide like whispered secrets beneath the soil. With each glistening droplet, the sundew casts its enchantment, inviting insects to a fatal dance. The unwary moth or fly, seduced by the glimmer, lands delicately upon the leaf, only to find itself ensnared in a trap more ancient than the stars.

As if by magic, the sundew’s tentacles begin to move, curling slowly like the fingers of a spellcaster weaving a protective charm. The sticky droplets bind the prey, while the tendrils pull it deeper into the embrace of the plant’s flesh. This slow, deliberate capture is a ritual as old as time itself—a dance of life and death played out beneath the watchful eyes of the forest spirits.

But the sundew is not cruel—it is simply a survivor in a world that demands resilience. From its trapped prey, it draws vital nourishment, a gift from the earth that it cannot obtain through its roots alone. Enzymes seep from the tendrils, dissolving the captured insect like a potion breaking down its components, allowing the plant to absorb the precious essences it needs to thrive in the barren bogs and acidic soils it calls home.

The sundew’s magic is ancient and widespread, with hundreds of species spread across the world—from the misty moors of Europe to the tropical rainforests of Australia. Each sundew wears its own unique cloak of colors and forms, some bright reds glowing like embers beneath the moonlight, others gentle greens kissed by the morning sun, all bound by the same mystical purpose.

In folklore, the sundew has long been regarded as a symbol of enchantment and transformation. It reminds us that beauty and danger often walk hand in hand, that life’s most delicate forms can conceal the fiercest will to survive. The sundew teaches patience and cunning, showing that sometimes, the greatest power lies in stillness and subtlety rather than brute force.

For those who cultivate sundews, the experience is nothing short of magical. Watching the tiny droplets glisten, sensing the slow, purposeful movements of the tentacles, one can almost hear the whispers of the natural world’s deepest mysteries. It is a living poem, an enchanted garden’s jewel, a reminder that even the smallest things can hold the greatest secrets.

So next time you find yourself near a quiet bog or a misty pond, seek out the sundew. Let your eyes rest on its shimmering leaves and let your imagination wander into the realms where nature’s magic thrives—where beauty traps, and every drop of dew tells a story of survival, enchantment, and the eternal dance of life.

Nature’s Tiny Hunters, Big on Wonder

Carnivorous plants are more than just botanical oddities—they're living examples of nature’s creativity and adaptability. Whether you’re fascinated by their insect-trapping abilities, looking for a unique addition to your plant collection, or simply want to spark curiosity in young minds, these remarkable plants offer beauty, mystery, and endless wonder. From science lessons to conversation starters, carnivorous plants prove that even the smallest, strangest organisms can capture our imagination—and sometimes a few bugs along the way.

This content is accurate and true to the best of the author’s knowledge and is not meant to substitute for formal and individualized advice from a qualified professional.

© 2025 Rebecca