How to be a Garden Season Shifter

Tricking Mother Nature's Rules

Years ago, I used to get my seed catalog right after the New Year, and start dreaming and planning my garden for spring/summer in Coastal Louisiana. Of course, the seed sellers are in the business of selling their wares, and put in the best possible pictures of flowers and produce that rarely measured up at harvest. Sometimes I wonder if the pictures are really plastic models.

But more than that, they usually never told the whole truth about what kind of heat most plants can tolerate. Cold hardiness maps, and growing zones were listed but there is a huge climate difference between Zone 9 in Northern California and Zone 9 in the Gulf South. Hostas that get to be giants in San Francisco, are puny little green blobs in a Southern garden.

I wasted a lot of money on seeds and plants before I realized that it is not just cold, but heat that also matters.

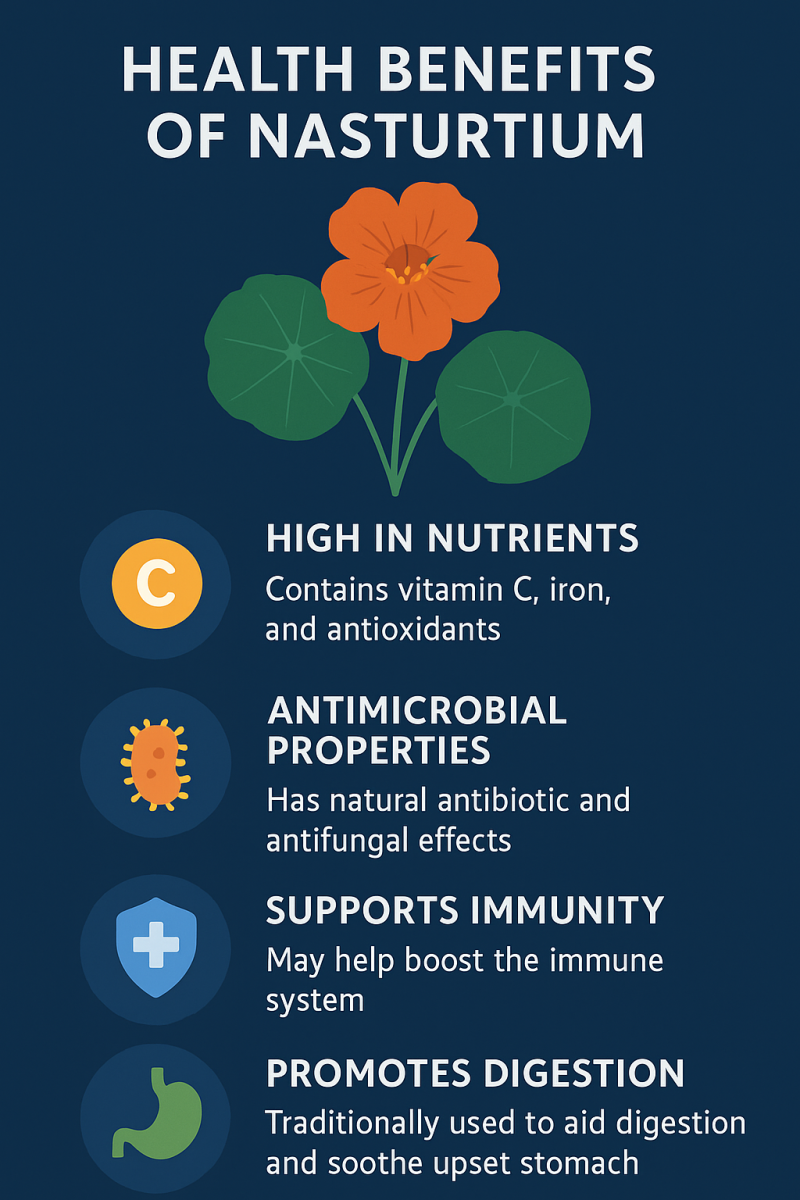

I was always jealous of gardeners in more Northern climates because they could grow wonderful flowers like peonies, nasturtiums, and fuchsias. If they planted tulips, they did not have to dig them up every fall, and put them in the refrigerator to get blooms the next year. They had the vegetable keepers in their fridge for food, not garden leftovers.

Everyone knew that it was a waste of shovel time to try planting celery, cauliflower, or broccoli. Radishes would grow pretty well in spring, but once the summer heat kicked in, they turned into little dinner plate fireballs. The climate is so hot, that there are many self respecting plants that simply won’t tolerate the heat.

Still there had to be more to life than zinnas, marigolds, and tomatoes, and I was determined to find the secret to growing different things.

Until I became a season shifter, I thought it was pointless to plant them. But I was wrong.

Over time, and with hours of research, I learned that I could grow snapdragons, bachelor buttons, nasturtiums, cosmos, asters, and larkspurs if I planted them in what was “officially” winter. By mid-February, I could set out seedlings of these plants and while they would only last until late May before the heat got them, I could have a lovely cottage garden with flowers no one in that part of the world grew.

If I planted my seeds inside at the end of the year, I had strong seedlings that would take off fast, once they were in full sun and heat.

Many times, those walking past my front cottage garden would stop to ask what some of the flowers were, and to comment on how charming my garden was. I had no mentor, just determination and common sense.

Of course, right behind that I had my seedlings of zinnas and marigold plants ready for late May, and let them have the hot weather they love.

From there, I started experimenting more. Some annual plants are true annuals, and won’t grow more than one season. But others, like nasturtiums, will last for several years in pots if you pull the blooms off before they set seed. They don’t like to have their roots disturbed, so if planted from the start in a large pot, they will slow down and look rather puny during the really hot months, but will start to flourish again in fall.

To be extra sure, I moved the pots into the shade of the carport during the hottest part of summer. While they did not get enough sun to thrive, the point was to keep the plant alive until fall when it would. And it worked. If you live in a really cold climate, and have some spare space inside, they can be held over until spring the same way.

My research opened up some other interesting opportunities. Pepper plants, whether mild or hot, are perennials originally from warmer parts of South America. I decided to experiment with holding over a particularly prolific jalapeño pepper plant. After all, there was nothing to lose because otherwise the plant would die in winter anyway.

I dug up the plant from the garden, as the end of summer approached, and put it in a large pot. Unless we were expecting a freeze, it stayed in the carport. Since it rarely freezes in South Louisiana, mostly it lived outside under a protected roof. By then I had named it Edgar. Again, the point was to keep Edgar alive, not producing. He came through winter intact, and in summer, I left Edgar in the pot, watered and fertilized him well, and he marched through summer producing buckets of peppers, and survived another winter. All told Edgar was with me three years.

After a successful first trial year, I discovered that my tomato plants performed better if the seedlings were planted out by late February. They could easily be covered if there were a late, short freeze, and it meant they had produced most of their fruit by the time the weather was scorching. Tomatoes stall when the temperatures get above 90º and they won’t set fruit until the night time temperatures are over 55º. But if you plant them out early, they will still get a good root system built by the time it is warm enough, and they will produce well before the heat stalls them.

The more I paid attention to what kinds of temperatures certain plants liked, the better I got at growing things that would not normally thrive in my climate. Broccoli or bok choy planted in late August would winter over fine and on those few times when the temperature froze, a light covering was all it needed to pull through fine. Lettuce would grow from fall to spring with little or no effort. Fuschias would grow well during fall, winter and spring, if protected from freezes, and would take its “winter” nap during the dog days of summer.

Even with my many efforts, peonies were beyond my reach. Some plants simply have to have a winter chill, or they will never perform. And since they don’t like to be disturbed after planting, putting them in the refrigerator for the winter was not an option. Not to mention, there is not exactly room for a huge root ball in the back of the fridge. And the only way to keep a tuberous begonia alive in the heat of the south is to water it by putting ice cubes around the base at night. Even that was a bit too much for me. But then, I will never grow lotuses in Oregon. And if I lived in the northern US, I would never grow caladiums either.

Season shifting works the other way too. Now, I live in the Pacific Northwest, and the summers are quite mild. The summer days are long, and pretty much anything grows here. Well almost. All of the veggies that thrive in intense heat, like eggplants, peppers, okra and lima beans are less impressed with the short “hot” season, and the milder summer temperatures.

Season shifting is not new here either. Tomato, peppers and eggplants can still be set out early if they are protected by a celled water sheath, like Wall o’ Water. Even so, they tend to grow slowly until the soil gets as hot as they like it. Gardeners who use plastic around their plants are always going to have a head start on harvest over those who don’t.

But tomatoes, peppers, eggplants commonly grow here.

Okra and lima beans need even more heat than those crops. And since you can’t always find them in a grocery outside of the South, even frozen, I had to succeed in growing them, or do without.

The first time I planted okra, the plants rotted from the rain. They can’t stand cool, wet weather. The second planting grew, but never had time to fully develop before the season ended that year. The second year, a more aggressive approach to season shifting was required. I put in raised beds with lots of compost, planted the seeds inside first, and when the weather finally warmed enough, planted them with black plastic around them. I was rewarded with a really nice crop. Fresh lima beans from raised beds ended up on the menu too.

No matter where you live, there will be some kind of gardening challenge. There is no perfect climate for everything you can find in a seed catalog. Decide what you want to grow. If it normally grows where you live, consider yourself lucky.

If you want to grow something exotic for your location, think creatively and season shift if you can. Some things may not work, but with adjustments in your garden habits, many will. Unless you are thinking about investing in a very expensive plant, experiment and see if you can get to your goal.

You might be surprised. And the process can be quite fun.