A DAY THAT CHANGED AMERICA

BATTLE OF ANTIETAM

A DAY THAT CHANGED AMERICA

150 years ago this year, on September 17, 1862, the bloodiest day in United States History occurred outside a sleepy, little town in Western Maryland called Sharpsburg. The Battle of Antietam (named for the meandering creek that ran near the hamlet) witnessed 23,000 Americans killed or wounded between one sunrise and sunset. Although tactically a draw, this Civil War engagement marked a dramatic turning point, not only in the conflict, but in the American story as well. For as a result of what happened in the rolling hills around Sharpsburg, President Abraham Lincoln determined to release the Emancipation Proclamation, which freed all slaves held in Confederate states on January 1, 1863.

The battle itself, and the events leading up to it, contain all the drama, intrigue and unsurpassed courage that make the Civil War era one of the most interesting in our history. By the summer of 1862, the Northern war effort to subdue the rebellious Southern states was going very badly in the eastern theater around Washington, D.C. The magnificent Army of the Potomac, created and drilled to precision by General George McClellan had stalled outside the Rebel capital at Richmond, Virginia. The troops were worthy, but McClellan or “Little Mac” had proved to be beyond timid when the guns began to roar. A second Union army under General John Pope, who was brought east by Lincoln to light a fire under McClellan, had also come to grief at the hands of General Robert E. Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia in August at Second Bull Run. Lee decided to press his advantage, cross the Potomac River into Maryland, and carry the war to the North.

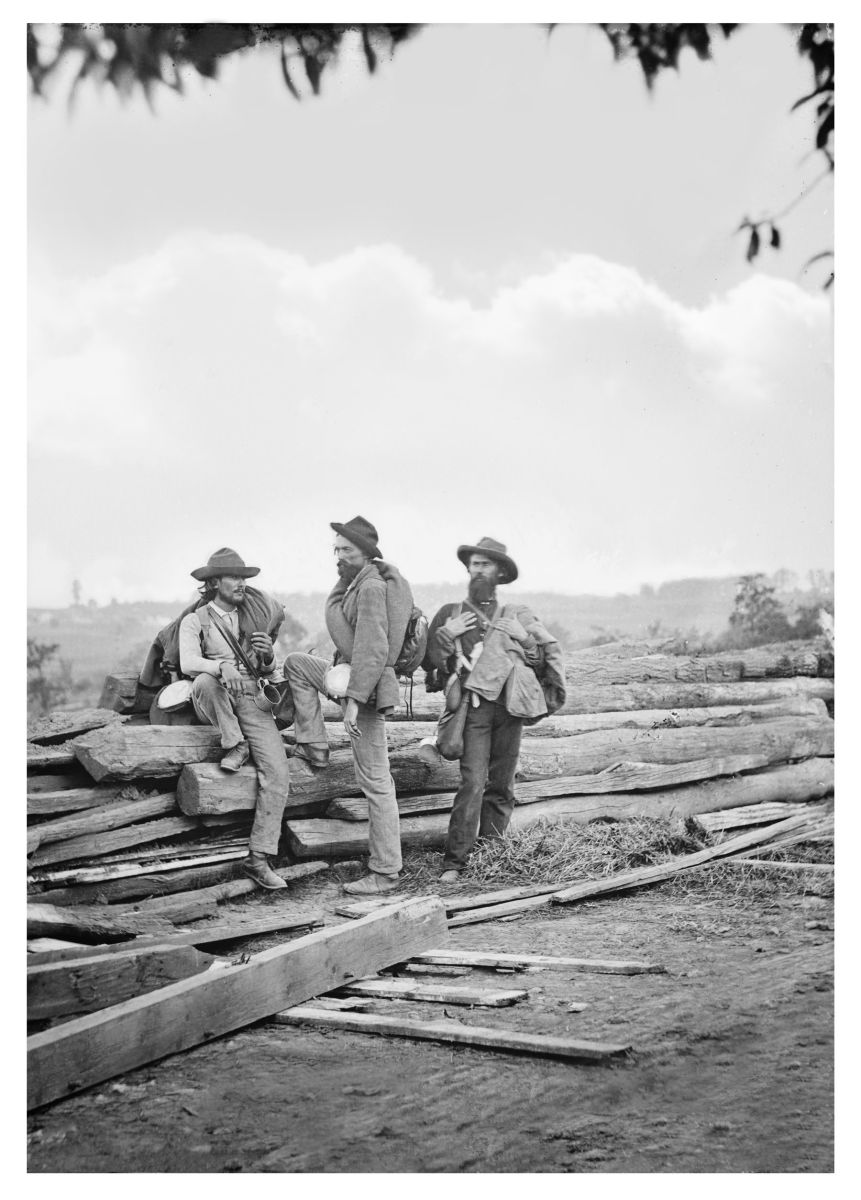

The mighty Rebel host began splashing across the Potomac in early September, where things started to unravel quickly for Lee. Many of his hardened veterans refused to set foot in Maryland, saying they had enlisted only to defend the South, not invade the North. Thousands more, possessing no shoes, fell out of the ranks once the army marched on Maryland’s tough, macadamized roads. Thus, the morning of September 17, Lee had less than 40,000 men ready for combat. To make it worse, one of his generals lost a copy of Lee’s orders, laying out the exact location of all Rebel units and what they were supposed to do. Two Yankee soldiers, relaxing in a field outside Frederick, Maryland, found the orders wrapped around several cigars. They were soon in the hands of General McClellan.

The only saving grace for General Lee was that the Army of the Potomac had been having troubles of its own. The biggest question facing President Lincoln, when he heard of Lee’s invasion, was who to place in charge of the Union pursuit. Both McClellan and Pope had turned up croppers. Pope ended up back in the west fighting Indians as fast as he came east. For his part, “Little Mac” not only lost his nerve in front of Richmond, but had deliberately withheld reinforcements from Pope when Lee was bearing down on that hapless general. Lincoln was appalled by McClellan’s actions, but faced an unpleasant truth- the Army of the Potomac loved “Little Mac” and still possessed faith in him. He might be the only general they would be willing to fight for after their demoralizing summer campaign. With the greatest reluctance, but feeling he had no choice, Lincoln placed McClellan in charge of the chase after the Rebels. The troops had a spring in their step as they set off into Maryland. When Lee’s orders were placed in his hands, “Little Mac” waved them jubilantly, shouting, “With this paper, if I cannot whip Bobbie Lee, I will be willing to go home!”

Unfortunately, McClellan’s spryness did not match that of his soldiers. He inexplicably waited 17 hours before getting the army in motion after being handed Lee’s orders. Precious time for the Rebel commander, who soon discovered his plans were missing, to gather his scattered forces at Sharpsburg. Even more dumbfounding, “Little Mac” delayed another whole day after reaching Antietam Creek on September 15, just outside the town, with 87,000 troops, more than twice as many as Lee’s force. The extra respite allowed additional Confederate reinforcements to reach the field the day of the battle, and help save Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia.

McClellan’s strategy called for attacks all along the Rebel lines, beginning on the left at dawn. Simple and effective, if the assaults took place simultaneously- the Northern superiority in numbers would most likely overwhelm the Confederates. Sadly, “Little Mac”, who stayed way to the rear when his battles were fought, did not coordinate the movements, which were delivered piecemeal, instead of all at once. This allowed Lee to shift his troops to threatened points throughout the long day. The fighting would be among the most ferocious ever engaged in by American soldiers. Common place names passed into legend: The Cornfield- where the bullets flew so fast and thick, not only did hundreds fall, but the cornstalks were cut as fine as if done by a scythe; The West Wood- 2,000 Union troops were shot down in less than 15 minutes after being trapped in a murderous crossfire; the Sunken Road- Rebel bodies were stacked 4 or 5 deep in this natural trench, created by countless farmers’ wagon wheels down the years.

There were unexpected moments of levity to break-up the dour grimness of the struggle. While marching across a farm yard to join the attack on the Sunken Road, a Pennsylvania regiment watched a cannonball plow through a neat row of beehives. The angry insects came swarming out, scattering the men in all directions. Then, there was the fiasco at a little bridge across the Antietam, named for the inept Yankee general charged with capturing it. General Ambrose Burnside, more famous to history for his luxurious sideburns than his military skill, sent wave after wave of attackers onto the bridge, only to see them beaten back by a single Georgia brigade perched on a hill along the far side. The Union troops could have easily waded the creek at several fords downstream from the bridge, but Burnside did not think of that until the whole morning was wasted. Several units did finally cross at the fords, while two regiments stormed across the bridge, after being promised a keg of whiskey by their colonel if they made it.

Despite the lengthy delay, Burnside’s men got around Lee’s right flank, bringing Union victory within sight. Alas, Rebel troops under A.P. Hill arrived in the nick of time to stop Burnside after making a prodigious 17-mile march to reach the field. The Battle of Antietam sputtered to a ghastly end. According to warfare protocol during the period, McClellan could claim victory as Lee retreated back to Virginia on September 19, leaving the Yankees in control of the battlefield. It was definitely not, however, the decisive triumph “Little Mac” had in the palm of his hand. Five days after the battle, on September 22, 1862, President Lincoln issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, which would go into effect on January 1, 1863.

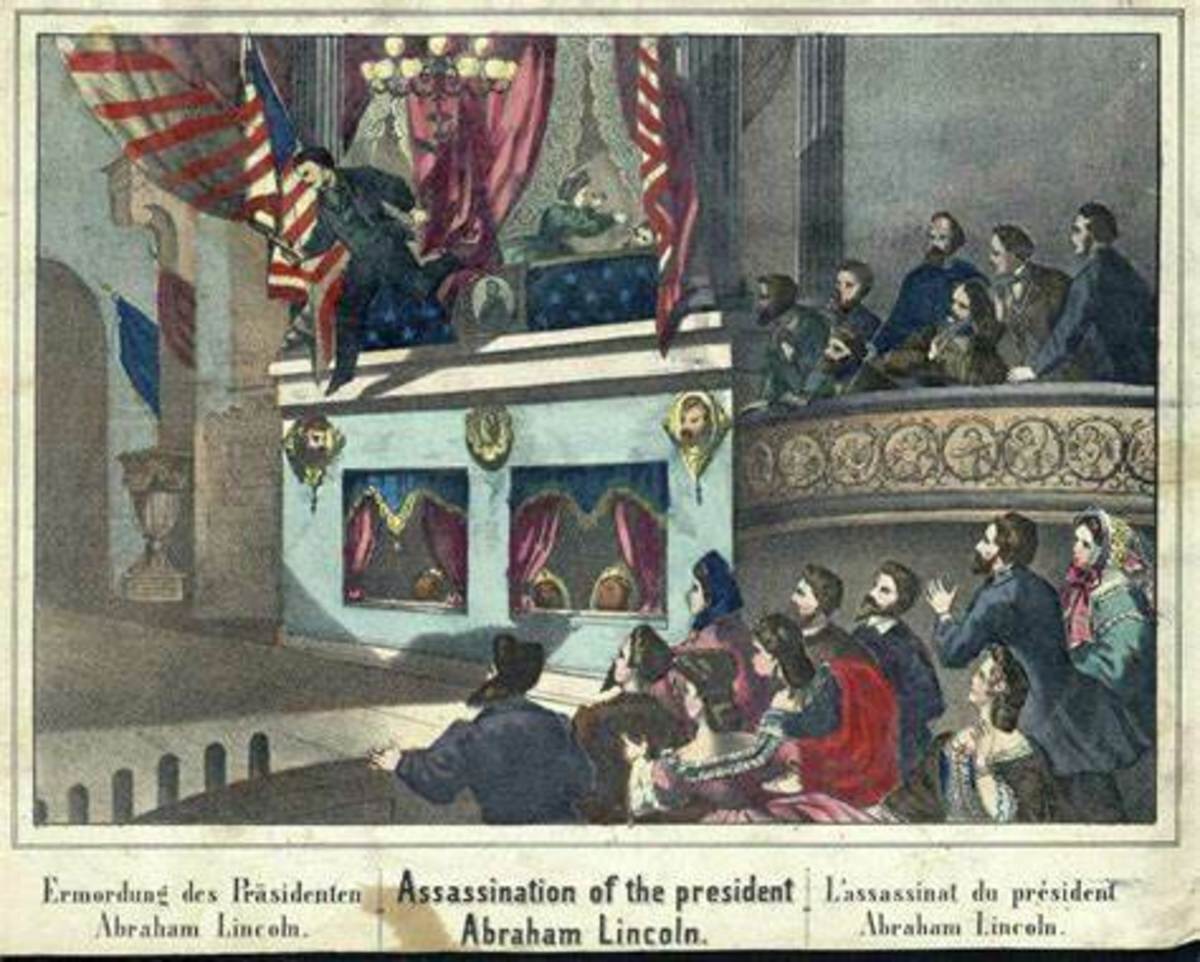

The Proclamation was criticized then and now for not feeing all the slaves, but it changed the war to a fight for human freedom, not only one to save the Union. Two years later, Abraham Lincoln led the drive to pass the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery permanently (so excellently portrayed in Spielberg’s new movie), several months before his assassination. In the last irony of Antietam, George McClellan had written Lincoln a letter in the summer of 1862, when rumors of an emancipation edict where swirling about, urging the president not to make the war about ending slavery. The vast majority of Northern soldiers would not fight for the “n-word” as McClellan so ungraciously put it. He was wrong. They would, but he did not. A month after Antietam, Lincoln sent George home, removing from command the general who had no pep in his step, and rocks in his head.