A Problem with Socialism, Libertarianism, and other "isms."

It Still Comes Down to Human Nature

Libertarians and socialists both envision worlds that I find somewhat appealing. Libertarians have a vision of America in which people are largely freed from the oppression of government and allowed to create their own destinies, and socialists dream of a place in which all of us have our basic needs met and wealth is spread more evenly. Laying out a vision, however, is a much easier process than bringing a better world into being. And maybe the most appealing thing about being on the political fringes in the United States is that you are not required to take any responsibility for the inevitable problems that arise in the real world. Because your faction is never given a chance to have any significant political power, budget deficits, social inequality, or whatever problems concern you are always the fault of those generic Democrats and Republicans who keep trading power back and forth.

History has clearly demonstrated, however, that neither libertarianism nor socialism has the capacity to eliminate a universal of civilized human societies: the dominance of a small class of elites. Now one could make the case that this is a ridiculous statement. In a pure sense, no society has ever been truly libertarian or socialist. But there have been places at certain times in history that adhered closely enough to these systems to demonstrate where they lead. For roughly the first one hundred years of American History, the role of the government, particularly at the federal level, was very limited. This was especially true in terms of any form of business regulation, with a generally laissez faire approach to managing the economy followed by leaders of whatever major political parties dominated the particular era. But instead of leading to a Jeffersonian ideal of self-reliant Americans enjoying the fruits of their own labor, the late 19th century saw the emergence of industries dominated by trusts and oligopolies, with men like Rockefeller, Carnegie, Morgan, and Vanderbilt amassing enormous fortunes. Meanwhile, employees of large corporations often worked and lived in lousy conditions, spurring the types of regulations that began to emerge by the early 20th century.

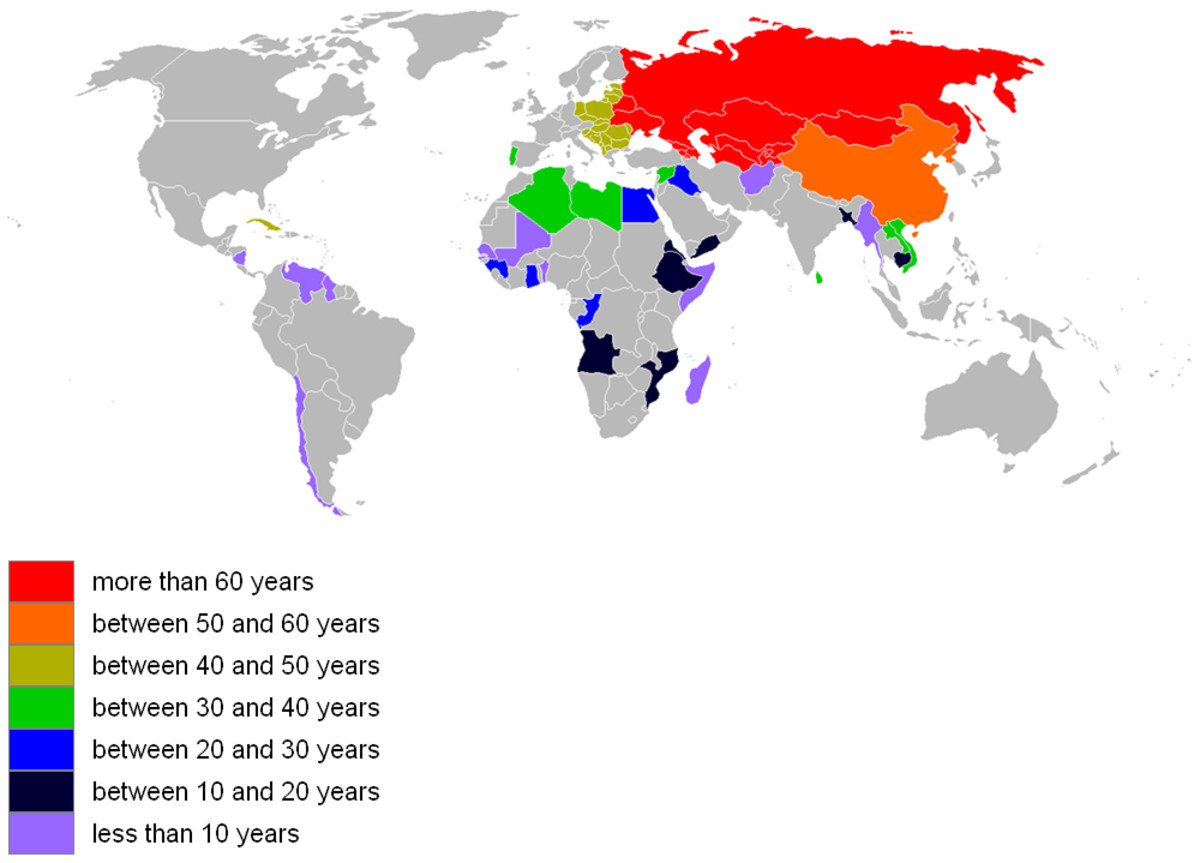

Americans, of course, are well versed with the failures of 20th century socialist experiments, with the Soviet Union and China often used as the poster children for the horrors of state-run economies. In addition to the rampant economic inefficiency and horrific suffering that resulted from both government incompetence and ruthless totalitarian rule, there was also the persistence of the inequality that socialism was supposed to eliminate. Inevitably, the people atop the communist party enjoyed a lifestyle superior to the general population whom they claimed to serve, in spite of whatever official communist ideology might say. By nature, the absolute power enjoyed by those at the top corrupted absolutely, with no socialist society every coming close to achieving the espoused goal of social and economic equality. The Soviet Union ultimately collapsed, and the Chinese communist party long ago gave up any pure adherence to socialism.

The key difference, then, between a libertarian and a socialist society is the identity of the elites. Pure libertarianism will lead to a dominant class of business elites, and socialism will lead to government leaders controlling the society. As mentioned earlier, however, you are hard pressed to find today any modern industrial societies that are close to being purely libertarian or socialist, with most attempting to strike a balance between government regulation/state-provided services and free market capitalism. But in the modern mixed economy of the United States, a relatively small class of elites still dominates both politically and economically, with many individuals and companies straddling the line between the public and private sectors and powerful people going back and forth between the "revolving door." With a public sector that represents more than one-fifth of the entire economy and that creates rules that impact nearly every aspect of our lives, it is no wonder that the private sector invests heavily into lobbying efforts in order to get their chunks of the government spending pie and to direct the rules to their benefit. To the average person, it can often feel like government and business leaders are colluding in order to screw over the rest of us average Joes. In theory, reducing the role of government will eliminate the need to lobby and lead to a more equal playing field for everyone. Excessive deregulation, however, will give the major corporate players the free reign that they want, which was a major reason for the lobbying in the first place. And once the inevitable, corporate winners become firmly established, there will be no equal playing field, regardless of what any libertarian idealists might believe.

None of this should be particularly surprising. We human beings, after all, are not fundamentally different from other creatures. We have within us the same competitive instincts that drive all life forms to survive in this harsh world and seek to pass on their genes to future generations. No matter what systems we humans might create, there are going to be winners and losers. The only question is whether or not we see this as a problem, and if it is a problem, is there anything that can really be done about it?

We humans spend a great deal of time arguing about ways to improve the systems that dictate how society functions, and these are worthwhile, important discussions to be having. It is also important to keep in mind, however, that human beings are in charge of carrying out these systems. So if the world is filled with competitive, selfish, corrupt, and/or incompetent individuals, a certain degree of corruption, inefficiency and inequality is inevitable. So when you get right down to it, the education of individuals will ultimately dictate humanity's fate, particularly since we live at a time when we humans are more dependent on one another than ever. And the most important subject in any field of knowledge may be professional ethics. I accept, after all, the idea that some people will be more successful than others. But I would like to have people setting up and enforcing rules who are truly committed to creating a playing field in which we all are at least given a decent chance.

For thousands of years, religious philosophers have been laying out a wide variety of theological systems. And while the major traditions that have survived the test of time disagree on many subjects, there seem to be a few basic things that they agree upon. One of these is a pretty simple concept: to have a better world, we need to be better people. To a large degree, systems are only as good as the people who are running them. This is why a Unitarian Universalist like myself can admit that there is something to be said for the idea of an ultimate judgment day. If nothing else, fear of either eternal suffering or of a lower birth in one's next life can lead us to view the world through a less selfish lens.

Or maybe we are not required to believe in a next life to be better people. Yes, we humans have the same self-centered instincts as other creatures. But somewhere back in that evolutionary tree, humans with a capacity to cooperate with other humans developed a better survival potential than those more centered on self. Working with others, it turned out, was an effective way to be selfish. So our inherently social nature is as much a part of our DNA as our instinct to focus on number one. Unfortunately, there was also a tribal component to our capacity to work with others, as we were often most driven to come together when there was another tribe to fight. But today, in our globally interconnected world, we humans may have the potential to recognize that playing a part in helping others is a very practical way to help ourselves. Maybe we can somehow see that everyone is increasingly a member of the same tribe. Or maybe this as big of a pipe dream as the faith that libertarianism or socialism will solve all of our problems.