A Reluctant Hero

By: Wayne Brown

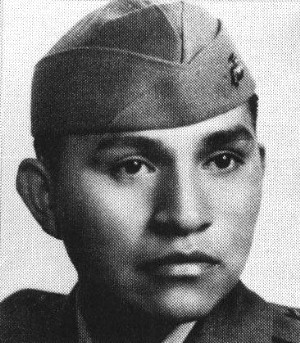

In Arlington National Cemetery near Washington D.C., there is a grave in Section 34, Plot 479A, of a young, Marine Corp Corporal. Here you will find the headstone and grave of an “Honorable Warrior” who fought in four major battles in the WWII Pacific combat theater with the U.S. Marine Corps, first serving as a paratrooper, then as an infantry rifleman. His service included the battles for Vella Lavella, Bougainville, The Northern Solomons Consolidation, and Iwo Jima. Here you will find a last tribute to a reluctant war hero, here you will find the grave of Native American, Ira Hayes, a Pima Indian.

Ira Hayes had no plan to achieve the fame assigned to him as one of the American soldiers caught in the act of hoisting the American flag over Mount Seribachi on the island of Iwo Jima. Ira longed for nothing more than an improvement in the respect and welfare of his people and the recognition of his fallen Marine comrades as true war heroes. At 32 years of age, he tragically died never having seen either of those wishes fulfilled in his short life span. From Ira’s perspective, his fame meant little when he was so powerless to accomplish his wishes. From Ira’s perspective, he had failed his people and he had failed his dead comrades. From Ira’s perspective, there was nothing associated with the term ‘hero’ that he would have used to describe himself.

Ira Hayes was born a member of the Pima Indian Tribe, a band of Native American Indians who resided in the confines of the Gila Bend Indian Reservation located in central Arizona, southwest of the Phoenix. The Pima Tribe successfully farmed the Arizona desert lands of the reservation for many generations using water for irrigation from the surrounding rivers and streams. Over the years, especially during the decades of the early 1900’s, more and more water sources were dried up or diverted to feed the needs of nearby settlements. By the time of Ira’s birth, the Pima Indians were a struggling, shrinking band deprived of the precious water needed to raise crops, feed them, and sustain their independence. Ira was born on January 12, 1923, into a life of abject poverty, and into a family that had little but the lore of their tribe to share. Ira would survive along with his family under these dire conditions through childhood and into manhood seldom ever venturing very far from the confines of the reservation. For all their woes, the Pima sustained their proud mindset and also their love of the land. Ira was immersed in this lore and these values that would shape much of his sense of duty and honor throughout his life. Ironically, these values would also drive the destruction that gnawed at his very soul.

Maybe it was fate that placed Ira Hayes on the top of Mount Seribachi, on the Island of Iwo Jima, that particular morning when a war correspondent captured on film a group of six soldiers raising the American flag. As the story goes, it was not the first flag raised over the island; it was actually the second, but it was larger and more easily seen by all of the Marines who were on the island. Neither event, either the first or second raising of the flag, was a ceremonious process and would have passed unnoticed had a chance photo by a war correspondent not recorded the now famed picture of six American soldiers raising Old Glory over the island. That photo in that moment would change the course of young Marine, Ira Hayes’ life forever.

Ira came away from Iwo Jima unscathed physically but emotionally scarred by the loss of so many of his comrade-in-arms in battle. Many of his friends had perished in the fighting that continued on Iwo Jima for a considerable time after the six soldiers raised the flag. In fact, three of the six would die in combat within days of the flag-raising. The remaining three, including Ira, would return to the USA only to realize the photo had made them ‘heroes’ in the eyes of the American public. They were ‘heroes’ who the government had every intention of parading through a 32 city tour before the public to raise bond sales to cover the cost of the war. Although Ira really wanted no part of the tour, he was a Marine and he would follow his orders like any good soldier.

Ira did not wear the moniker of ‘hero’ well from the very start. He considered the heroes to be all his fallen comrades who had their lives snuffed out in the battle to capture Iwo Jima. In Ira’s Marine platoon of 45 men, only five survived the island assault. In his Marine Company of 250 men, only 28 survived the action. Ira was alive and back home being hailed as a hero and he did not know why. As a soldier, he had tried to serve in a way so as to make his family and his people proud but he saw nothing about that which was heroic. Nor did he see the heroic nature associated with raising a flag. Ira failed to realize that the photo had made him a symbol of heroism. Ira’s image would become one of the faces symbolic to the American public of the heroism of the American soldier. There is no evidence that Ira ever saw himself from that perspective. Had Ira gained that awareness, possibly the hero moniker might have been easier to bear. Without that awareness, he was immersed in the guilt of his own survival over his comrades.

Like a good soldier, Ira toured around the country with his two flag-raising comrades. At each stop, there was ceremony and celebration, hand-shaking, pictures to be made and autographs to be signed. A drink was never far from Ira’s reach and the alcohol helped him salve the guilt and hypocrisy that welled up inside him as he enjoyed the best that America had to offer while his people were starving on the reservation down in Arizona; while comrades lay dead in their graves. If this was what it felt like to be a hero, Ira wanted another drink and then another, and then another until he did not feel or remember much of anything anymore.

Eventually the tour did end, but, for Ira, the damage had been done. He would never be quite the same. He seemed to have lost himself both as a proud Native American and as a Marine who had served his country honorably. He seemed to have lost sight of the fact that he had been an “Honorable Warrior”. The war was over; the bonds were sold, the tour was done. Basically, the government was done with Ira and he was free to return to his people and the dire poverty of reservation life. Ira had come full circle and was standing back where he had started before the war, only now he was a ‘war hero’. War hero or freak, Ira was not sure. Tourists seemed to find their way to the reservation to inquire if he was that ‘Indian who had raised the flag’? They came to see the freak, possibly? Ira just wanted all of it to go away…the tourist, the questions, the guilt, the memories…just go away. Alcohol, in sufficient quantity, could grant those wishes, but only temporarily at best.

Ira had returned to his people and the Arizona reservation with his emotions tucked deep inside. It was a rare occasion that he would speak of the flag-raising. He was more likely to speak of his fallen comrades, their service, and how proud he had been to serve in the Marine Corps. When he did speak of the flag-raising, it was likely to be at a point when he was far too deep in the bottle to ever remember it the next day. Public drunkenness was habitual with Ira being arrest more than 50 times in this condition. He worked at various menial jobs around the reservation but his stint as a soldier stands as the only time in his life that he was focused on a singular task for any length of time.

Ira did return briefly to the public eye when he and his two flag-raising comrades appeared as themselves with John Wayne in the movie, “Sands Of Iwo Jima”. He quickly returned to his seclusion and the comfort of the bottle. He remained in this obscurity gaining more fame as a drunk than as a hero. He reluctantly made his last public appearance when he was asked to go to Washington D.C. for the formal dedication of the Iwo Jima Memorial in 1954. Hayes suffered through the event as President Dwight Eisenhower, in the dedication speech, referred to the three surviving flag-raisers as heroes. Ira could only wait for a return to a drunken autonomy on his reservation.

On January 24, 1955, Ira Hayes was found dead. He had spent the night before drinking with friends as they played cards. The night would eventually end on a sour note as a fight broke out between Ira and one of the others and a struggle ensued. Although some suspected foul play, the local coroner ruled that Hayes had died from the combined effects of alcohol and exposure. Ironically, Hayes' lifeless body lay in the irrigation ditch that fed precious water to the Pima Indian crops; a ditch that in years past had been dry too often; a ditch on a piece of ground that Pima Indian, Ira Hayes, was moved to defend through his service in the Marine Corp. Ira Hayes had died like he had so often lived…alone, alone in a land he wanted to think had been saved by the blood of his fallen comrades. Ira Hayes, the “Honorable Warrior” had departed this life where he suffered as a “Reluctant Hero.”

In the aftermath of his death, songwriter, Peter Lafarge would immortalize Hayes in his song, “The Ballad Of Ira Hayes” which painted a sad memory of Ira against the backdrop of the Pima Indian Tribe struggles. The chorus registers the sad refrain of Ira’s short 32-year life with the words, “Call him drunken Ira Hayes, he won’t answer anymore, Not the whiskey drinkin’ Indian or the Marine that went to war. Yeah, call him drunken Ira Hayes, but his land is just as dry, and his ghost is lying thirsty in the ditch where Ira died.” God Bless You, Ira. I hope you found your peace in the hereafter.