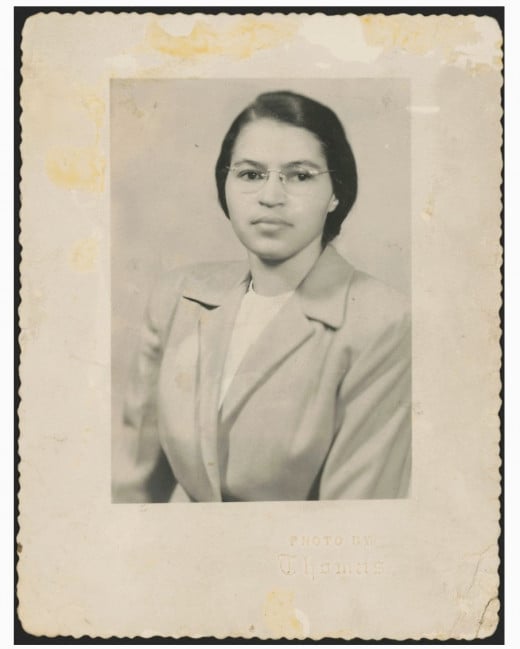

A Woman Takes a Seat for Civil Rights

The History of Rosa Parks

Civil Rights Act of 1964

The Montgomery Bus Boycott that began in 1955 was a major contributor to the African American civil rights movement, which also paved the way for women’s rights in the United States. Interestingly, the Montgomery Bus Boycott fell upon the actions of one African American woman: Rosa Parks. While the Montgomery Improvement Association, Women’s Political Council, and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People had already discussed the idea of a bus boycott and some African Americans had already been arrested for violating Montgomery bus policy, the arrest of Parks on December 1, 1955 for refusing to give up her seat to a white man became the planned trigger point for the beginning of the Montgomery Bus Boycott.[1]

News of her arrest spread quickly, and 42,000 African Americans in Montgomery boycotted buses for 381 days from December 5, 1955 to December 21, 1956.[2] The United States Congress deemed Parks “the first lady of civil rights,” as well as “the mother of the freedom movement.”[3] The civil rights movement that would ensue in the years that followed brought down the walls of discrimination against African Americans, as well equality of law to all Americans, men and women, through the Civil Rights Act of 1964.[4]

Jim Crow Laws

Rosa Parks was born in a time where segregation laws were in full effect, especially after the Supreme Court decision in Plessy v Fergusson of 1896 that instituted Jim Crow laws in the South. In response to Jim Crow laws, The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People was founded in 1909 by black and white intellectuals of New York. By the time Parks was born in 1913 however, President Woodrow Wilson’s administration initiated racial segregation in the workplaces, restrooms, and lunchrooms across all federal offices.

In 1915 William Simmons revived the white supremacist group Ku Klux Klan in Georgia, and the Great Migration of African Americans from the South to the North began in response to increased violence against African Americans.[5] Just as the United States had entered the World War I arena in 1917, the NAACP organized the first protest of the 20th century against mob lynching, race riots, and rights oppression.[6] Interestingly, the Supreme Court then struck down ordinances in Louisville, Kentucky that mandated segregated neighborhoods in the decision for Buchanan v Warley.

By the time Rosa Parks entered elementary school in 1918, 83 African Americans were lynched; and, many of these African Americans were soldiers in the United States military that fought in WWI. By the time she graduated from high school in 1933 after being married to Raymond Parks in 1932, 25 race riots took place during the “Red Summer” of 1919, a minimum of 60 blacks and 21 whites were killed in Tulsa, Oklahoma during a race riot in 1921, the predominantly black town of Rosewood, Florida was destroyed in 1923 by a mob of white residents in nearby communities, the Scottsboro Boys were arrested in Alabama in 1931 on alleged charges of rape, in addition to several other racial struggles.[7]

Women Activists

Given the racial environment that existed during Rosa Parks’ life, it is no surprise that her arrest would trigger a civil rights movement for African Americans and women of all races alike. While the Montgomery Improvement Association, an organization to which Parks belonged, had been planning a bus boycott for some time, refusing to give up her seat on that particular day was not part of the bus boycott plan. She recalled in an article with Ebony magazine, “I really don’t know why I wouldn’t move.” She further stated that “there was no plan at all. I was just tired of shopping.”

Parks was 42 at the time she was arrested, and was by no means an unintentional hero. She was not only a member of the Montgomery Improvement Association, but also the secretary for the Montgomery branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Both of these organizations had been preparing for change particularly in segregation policy on public buses in Montgomery, and Parks was actively present in the planning meetings. She had worked in other civil rights activities, including voter registration campaigns and NAACP youth councils.

Rosa Parks also worked with a group of African American women activists, who struggled against the forces of white supremacy and for the ideals of social justice. In fact, the civil rights movement was in large part supported by African American women striving for both racial and gender equality. She did not accidentally wander into the course of African American history, rather she followed a course that would place her in the center of a civil rights movement.[8]

Human Rights

Rosa Parks dedicated her life to the cause of human rights, embodying a love of freedom and humanity.[9] With a quiet valor and enduring threats of death, she symbolized the ideal of nonviolent protest that Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. spoke and wrote about.[10] Because of her character and reputation, the Montgomery Improvement Association chose Parks to initiate the Montgomery Bus Boycott.[11] Parks became the first woman in the Montgomery Chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, an active volunteer for the Montgomery Voter’s League, and co-founder for the Rosa and Raymond Parks Institute for Self Development.[12]

Because of her great efforts, Parks became the recipient of several awards on behalf of civil harmony, such as the Spingarn Award, the highest honor for NAACP’s civil rights contributions, Presidential Medal of Freedom, the Nation’s highest civilian honor, and the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center’s first International Freedom Conductor Award.[13] She was also awarded the Congressional Gold Medal, which was presented to her by the President of the United States on behalf of Congress, for her contributions to a better nation.[14] To be sure, she became an icon for freedom in America.[15]

Works Cited

[1] The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute, “Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Global Freedom Struggle: Montgomery Bus Boycott" (Stanford, CA: Stanford University, 2013).; U.S. Government Printing Office, 106th Congress Public Law 106 (approved May 4, 1999), Section 1:3.

[2] U.S. Government Printing Office, Section 1:4.

[3] U.S. Government Printing Office, Section 1:2.

[4] U.S. Government Printing Office, Section 1:6.

[5] Joyce A. Hanson, Rosa Parks: A Biography (Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood, 2011), xvii.

[6] Hanson, xvii-xviii.

[7] Hanson, xviii.

[8] Hanson, xi.

[9] U.S. Government Printing Office, Section 1:8.

[10] U.S Government Printing Office, Section 1:10.

[11] The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute, “Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Global Freedom Struggle: Montgomery Bus Boycott" (Stanford, CA: Stanford University, 2013).

[12] U.S. Government Printing Office, Section 1:9.

[13] U.S. Government Printing Office, Section 1:7.

[14] U.S. Government Printing Office, Section 2:a.

[15] U.S. Government Printing Office, Section 1:11.

© 2014 Marilyn Prado