Analysis of the Bush Administration’s Iraq War Propaganda Using the Jowett and O’Donnell Method of Propaganda Analysis

On March 20, 2003, under the leadership of President George W. Bush, the United States of America preemptively attacked and invaded the sovereign country of Iraq. Before the invasion, the Bush administration began to conduct a domestic and international propaganda campaign to raise public support for a U.S. lead war against Iraq. Iraq had been under United Nations (U.N.) sanctions for about twelve years due to violations of U.N. resolutions regarding Iraqi weapons disarmament (U.N., 2004). On numerous occasions, U.S. military forces had enforced the U.N. designated no fly zones in Iraq. Although the media had previously discussed possible U.S. military use of force against Iraq, no formal campaign to promote this option had been previously undertaken.

This hub presents a detailed analysis of the Bush administration’s domestic Iraq war propaganda campaign [hereafter referred to as the Campaign] starting from President Bush’s January 2002 State of the Union address through to the start of the war. This starting point was chosen because it was during this address that President Bush formally declared Iraq to be part of “an axis of evil” that was in possession of weapons of mass destruction (WMD), supported terrorism, and was a threat to the United States (Bush, 2002, January 29).

The ending point was chosen because the propaganda campaign began to change focus in attempt to justify U.S. military and Iraqi civilian casualties as well as the occupation of Iraq. Although the campaign included foreign propaganda, this analysis will only address the domestic campaign from inception up to the start of the war. The method of analysis uses Jowett and O’Donnell’s ten-step propaganda analysis plan as outlined in their book, Propaganda and Persuasion (1999).

The Ideology and Purpose of the Propaganda Campaign

Proper analysis of a propaganda campaign involves examining the beliefs, attitudes, values, and behaviors that the campaign encourages (Jowett and O’Donnell, 1999). The Bush administration’s Iraq war domestic propaganda campaign intended to raise public support for a U.S. lead war against Iraq. The campaign attempted to instill the belief that the regime of Saddam Hussein was a dangerous threat to the safety of the U.S. and that military action was the only solution to stop this threat. In the beginning of the campaign, the propaganda emphasized the danger that Iraq posed and did not specifically call for military action; however, the president made it clear that time was running out for Saddam Hussein and that the U.S. would take any actions necessary to protect itself. President Bush provided several reasons why Iraq was a threat to the U.S. in his January 2002 state of the union address:

Iraq continues to flaunt its hostility toward America and to support terror. The Iraqi regime has plotted to develop anthrax, and nerve gas, and nuclear weapons for over a decade. This is a regime that has already used poison gas to murder thousands of its own citizens … This is a regime that agreed to international inspections [under the U.N.] -- then kicked out the inspectors. By seeking weapons of mass destruction, these regimes [Iran, Iraq, and North Korea] pose a grave and growing danger. They could provide these arms to terrorists, giving them the means to match their hatred. They could attack our allies or attempt to blackmail the United States. We know that Iraq and the al Qaeda terrorist network share a common enemy – the United States of America. We know that Iraq and al Qaeda have had high-level contacts that go back a decade. Some al Qaeda leaders who fled Afghanistan went to Iraq. … We’ve learned that Iraq has trained al Qaeda members in bomb-making and poisons and deadly gases. (Bush, 2002, January 29)

In his speech, the president outlined four major beliefs about the danger that Iraq posed to the U.S, stating that Iraq.:

1. Supported terrorism (specifically Al-Qaeda)

2. Possessed weapons of mass destruction (WMD)

3. Has used WMD’s on their own people

4. Is in violation of U.N. resolutions

The Campaign repeatedly stated these core beliefs with varying emphasis. During this time the U.N. was trying to utilize all diplomatic means available to resolve the situation with Iraq, but the patience of the Bush administration was wearing thin. Although not specifically calling for military action, in the same address, the president goes on to state that the status quo in Iraq cannot continue:

In any of these cases, the price of indifference would be catastrophic. We will work closely with our coalition to deny terrorists and their state sponsors the materials, technology, and expertise to make and deliver weapons of mass destruction. … And all nations should know: America will do what is necessary to ensure our nation's security. We'll be deliberate, yet time is not on our side. I will not wait on events, while dangers gather. I will not stand by, as peril draws closer and closer. The United States of America will not permit the world's most dangerous regimes to threaten us with the world's most destructive weapons. (Applause.) (Bush, 2002, January 29)

President Bush continued using the same rhetoric against Iraq in the fall of 2002:

The threat comes from Iraq. It arises directly from the Iraqi regime’s own actions – its history of aggression, and its drive toward an arsenal of terror. Eleven years ago, as a condition for ending the Persian Gulf War, the Iraqi regime was required to destroy its weapons of mass destruction, to cease all development of such weapons, and to stop all support for terrorist groups. The Iraqi regime has violated all of those obligations. It possesses and produces chemical and biological weapons. It is seeking nuclear weapons. It has given shelter and support to terrorism, and practices terror against its own people. The entire world has witnessed Iraq’s eleven-year history of defiance, deception and bad faith. (Bush, October 7, 2002)

In this address the president not only reviews the danger that he believes Iraq poses, but also puts blame upon Iraq, as if he is emphasizing that it “is their fault.” A possible reason for this is to deflect any accusations of U.S. responsibility for the current Iraqi threat that might originate from a New York Times report published less than two months earlier that said:

Unidentified senior US military officers say covert US program during Reagan administration provided Iraq with critical battle planning assistance at time when US intelligence agencies knew Iraqi commanders would employ chemical weapons against Iran; comments respond to query about gas warfare on both sides during Iran-Iraq war; Iraq's use of gas is repeatedly cited by Bush administration in calling for regime change now … (Tyler, 2002, August 18).

One important belief in the propaganda campaign is that Iraq had connections to terrorists, in particular, Al-Qaeda, which was responsible for the 9-11 attack on the U.S. In his 2003 state of the union address, President Bush continued to claim that there was a connection between Iraq and Al-Qaeda:

On September the 11th, 2001, the American people saw what terrorists could do, by turning four airplanes into weapons. We will not wait to see what terrorists or terrorist states could do with chemical, biological, radiological or nuclear weapons. Saddam Hussein can now be expected to begin another round of empty concessions, transparently false denials. No doubt, he will play a last-minute game of deception. The game is over. … With nuclear arms or a full arsenal of chemical and biological weapons, Saddam Hussein could resume his ambitions of conquest in the Middle East and create deadly havoc in that region. And this Congress and the America people must recognize another threat. Evidence from intelligence sources, secret communications, and statements by people now in custody reveal that Saddam Hussein aids and protects terrorists, including members of al Qaeda. Secretly, and without fingerprints, he could provide one of his hidden weapons to terrorists, or help them develop their own. (Bush, 2003, January 28)

The Bush administration attempted to use the existing domestic and international support for the War on Terrorism and funnel it towards support for military action against Iraq. This accounts for the propaganda campaign’s continued attempts to connect Iraq with 9-11, which was successful at first, but later failed because evidence was disproved. However, by that time, much of the American public rallied against Iraq.

There was much public debate about the evidence used to support the administration’s claims that Iraq currently possessed WMD’s (including nuclear weapons) and had official connections with Al-Qaeda. In the fall of 2002, the Campaign began to strongly emphasize the need to liberate the Iraqi people as a defense for U.S. preemptive military action against Iraq. In August, Vice President Cheney said, “With our help, a liberated Iraq can be a great nation once again” (2002, August 29). In October, Deputy Defense Secretary Wolfowitz said, “To the contrary, I believe there’s actually a great opportunity here to liberate one of the most talented populations in the Arab world …” (2002, October 28). In February 2003, he said, “should military force become necessary to liberate Iraq from Saddam Hussein … the United States seeks to liberate Iraq, not occupy Iraq” (Wolfowitz, 2003, September 23). The next month President Bush spoke about the need to help the Iraqi people, saying,:

For decades he [“the dictator of Iraq”] has been the cruel, cruel oppressor of the Iraq people. … We must not permit his crimes to reach across the world. … Action to remove the threat from Iraq would also allow the Iraqi people to build a better future for their society. And Iraq's liberation would be the beginning, not the end, of our commitment to its people. (Bush, 2003, March 16)

Deputy Defense Secretary Paul Wolfowitz explains why the Bush administration agreed to initially focus on WMD’s as the primary reason for going to war with Iraq:

The truth is that for reasons that have a lot to do with the U.S. government bureaucracy we settled on the one issue that everyone could agree on which was weapons of mass destruction as the core reason, but . . . there have always been three fundamental concerns. One is weapons of mass destruction, the second is support for terrorism, the third is the criminal treatment of the Iraqi people. Actually I guess you could say there’s a fourth overriding one which is the connection between the first two. (Wolfowitz, 2003, May 9)

Wolfowitz’s third reason, Saddam’s treatment of his people, originally took a back seat to the discussion about the threat of WMD’s, but as some evidence for the existence of WMD’s was disproved, it gradually was presented as a primary reason for the US invasion of Iraq.

The attitude of President Bush and his administration played a roll in the Campaign. Former staff of the Bush administration said that President Bush was thinking about invading Iraq soon after he was sworn into office (O’Neill, 2004, January 14). In 2002, President Bush said, “After all, this is a guy [Saddam Hussein] that tried to kill my dad at one time” (Bush, 2002, September 26). The war with Iraq was something personal for President Bush. Aside from President Bush's personal reasons that could have affected his attitude, the entire Bush administration exhibited an intimidating and unilateralist attitude, often with black and white thinking and a sense of religious righteousness. The vice president and several prominent cabinet members were strong advocates for an attack upon Iraq. Although the Bush administration attempted to obtain a UN resolution for an invasion of Iraq, President Bush was seen by many to be contemptuous of the UN and the world community. Regarding this matter he has said:

Secondly, I’m confident the American people understand that when it comes to our security, if we need to act, we will act, and we really don’t need United Nations approval to do so. I want to work – I want the United Nations to be effective. It’s important for it to be a robust, capable body. It’s important for it’s words to mean what they say, and as we head into the 21st century, Mark, when it comes to our security, we really don’t need anybody’s permission (Bush, 2003, March 6).

When France, Germany, and Russia failed to back the U.S. sponsored resolution, the Bush administration made it clear that failure to support the U.S. might result in unpleasant consequences, as indicated in a PBS interview with U.S. Secretary of State, Colin Powell:

MR. ROSE: Okay, but I’ve heard there will be consequences because they [France] were tough for you. I mean everywhere you would turn after the vote on (inaudible) they weren’t on your side and with you; they were against you, against the United States. Are there consequences for standing up to the United States like that?

SECRETARY POWELL: Yes (Powell, 2003, April 22).

Interestingly, in a Whitehouse press briefing, Press Secretary Ari Fleisher hinted that someone in the Air Force made the decision to change “French toast” to “freedom toast” on the menu selection on Air Force One (Fleisher, 2003, March 28).

The black and white thinking of the Bush administration was evident early in the president’s term when he said,

Every nation, in every region, now has a decision to make. Either you are with us, or you are with the terrorists. (Applause.) From this day forward, any nation that continues to harbor or support terrorism will be regarded by the United States as a hostile regime.

— (Bush, 2001, September 20)Bush also demonstrated this attitude to the U.N., saying:

We will continue to work with our friends, people who understand the value of freedom. We will insist that the United Nation Resolution 1441 be adhered to in its fullest. After all, we want the United Nations to be a legitimate, effective body. But for the safety of the American people and for peace in the world, Saddam Hussein will be disarmed, one way or the other. And this nation does so for the sake of peace (Bush, 2003, February 26).

Another example of this type of thinking was the president’s categorization of things as either good or evil, such as his statement, “States like these [North Korea, Iran, and Iraq], and their terrorist allies, constitute an axis of evil, arming to threaten the peace of the world (Bush, 2002, January 29). With a similar attitude Secretary of State Powell said, “We are also examining what other options may be available to change this evil regime [Iraq]”(Powell, 2002, March 27). President Bush exhibited other examples of unilateralism and arrogance through breaking signed treaties. On May 6, 2002, the United States informed the U.N. that despite its signing on July 17, 1998, the U.S. was no longer a party to the International Criminal Court treaty (Boucher, 2002). In 2001, the Bush administration also withdrew from the 1972 ABM treaty with Russia (Bush, 2001, December 13). Earlier in the same year under the leadership of President Bush, the U.S. withdrew from the 1997 Kyoto Treaty regarding global warming and green house emission cut backs (CNN, 2001).

President Bush has not been one to hide his religious beliefs; he often referred to God in his speeches and at times exhibited a religious righteousness, as demonstrated in his 2003 State of the Union address:

Americans are a free people, who know that freedom is the right of every person and the future of every nation. The liberty we prize is not America’s gift to the world, it is God’s gift to humanity. (Applause.) We Americans have faith in ourselves, but not in ourselves alone. We do not know – we do not claim to know all the ways of Providence, yet we can trust in them, placing our confidence in the loving God behind all of life, and all of history. May He guide us now. And may God continue to bless the United States of America. (Applause) (Bush, 2003, January 28).

Another attitude of the Bush administration, and of many Americans, was that the enemies of the U.S., particularly terrorists, hate America for what it is instead of for what it does in it’s foreign policy. President Bush makes this clear when he says:

Americans are asking, why do they [Al-Qaeda] hate us? They hate what we see right here in this chamber – a democratically elected government. Their leaders are self-appointed. They hate our freedoms – our freedom of religion, our freedom of speech, our freedom to vote and assemble and disagree with each other. (Bush, 2001, September 20).

The Campaign emphasized the value of American security, sovereignty, sacrifice, and freedom over all else. These values often ring true with many Americans. In 2003 President Bush said:

The United States and other nations did nothing to deserve or invite this threat. But we will do everything to defeat it. … before it is too late to act, this danger will be removed … Americans understand the costs of conflict because we have paid them in the past. War has no certainty, except the certainty of sacrifice. … The security of the world requires disarming Saddam Hussein now. As we enforce the just demands of the world, we will also honor the deepest commitments of our country. Unlike Saddam Hussein, we believe the Iraqi people are deserving and capable of human liberty. (Bush, 2003, March 17).

America often views itself as the bastion of freedom and democracy and believes it has the duty to propagate these values throughout the world. It is easy for the American public to identify with Campaign rhetoric that speaks of liberating others, even if it means sacrifice. This is part of America’s historical frame of reference, seen through wars of liberation from the American Revolution, World War I and II, Vietnam, the Gulf War, and military actions in between. Europeans colonized the land of several different countries; America seeks to colonize socio-political systems and transform them into democracies.

The Context in Which the Propaganda Occurs

Though still a young country compared to many in the world, the U.S. does have over 200 years of history that has helped to form today’s society and culture. Otteson (2004) relates four American myths, symbolized in famous American literature, that have shaped American society. They are: “the myth of the land and frontier freedom,” as described in My Antonia; “The Puritan myth and the model family,” revealed in the Scarlet Letter; “Individual opportunity and the American Dream,” as described in The Great Gatsby; and the “myth of the melting pot,” as related by the Invisible Man. These four works of literature, studied by almost every high school student in America, reveal deep cultural beliefs about American society.

America’s founders had a pioneer spirit of adventure and freedom-seeking that many ascribe to today, but are all too often denied. Puritan teaching of ideals, moral absolutes, hierarchy, and religious authority was the foundation of the early colonies and remains a strong influence to many today through such religious expressions as conservative evangelicalism, and to an extent, even our own political system. The American dream is often that, a dream. Yet, many grow up believing in that dream – some achieve it and some continually struggle. The results often help to shape one’s political outlook. America is not a melting pot, it is more like a stew. To this day, racism, sexism, homophobia, and religious intolerance continue as mitigating factors in modern day society. Together, these beliefs, and many more, compose the soil for any propaganda campaign.

The Campaign under analysis made good use of American cultural myths. President Bush has said, “… America stands for a great cause, and that is freedom. We love, we cherish, and we will defend freedom at any cost” (Bush, 2002, February 8). President Bush himself acknowledged the Puritan influence in American culture saying, “It's rightly said that Americans are a religious people. That's, in part, because the "Good News" was translated by Tyndale, preached by Wesley, lived out in the example of William Booth. At times, Americans are even said to have a puritan streak -- where might that have come from? (Laughter.) Well, we can start with the Puritans (Bush, 2003, November 19) [though this quote was made after the war started, it serves to represent the ideology of President Bush]. There are many instances of President Bush referring to “the American Dream,” and there was even an appropriations bill named “The American Dream Downpayment [sic] Act of 2003” (Bush, 2003, December 16). The melting pot myth was used by the president to rally nationalism, often using the words “one people” or “Americans,” to lump everyone together to rally behind the flag and the president’s Campaign.

In addition to American cultural myths, there is the entire history between the Arab and Western civilizations, including the Crusades, Western colonization in the Middle East, support of Israel, and Arab hostage taking of Westerners. The two cultures and religions are quite different, which leads to fertile ground for propaganda advocating military action against an Arab country.

Cultural and historical background is important in understanding the cultural climate of the Campaign, yet current events are also quite relevant. When the Campaign began, the U.S. was already in the middle of a global war on terrorism with a large military campaign being conducted against the Taliban regime in Afghanistan. America was still in grief over the attacks of 9-11, which occurred just four months earlier. The entire country was on a heightened sense of alert and had a desire for retribution. According to a 2001, September 25-27 Washington Post poll, American patriotism was at a peak with 75 percent of the American public considering themselves “strongly patriotic” and 22 percent “somewhat patriotic” (Washington Post). The Campaign used this energy to promote a war against Iraq. The issue was whether the American people would support such a war. Failure would have been disastrous for the Bush administration. There was already talk of “another Vietnam,” and many throughout the world accused the U.S. of unilateralism and proceeding on a dangerous course. Interestingly, only a few days before President Bush made his famous “axis of evil” statement, The Pew Research Center published a survey report that said 73 percent of the public was in favor of using military force to remove Saddam Hussein from power. This number fell to 56 percent if the potential for large U.S. casualties was mentioned. Of those agreeing that the U S. should use force, 53 percent believed that the U.S. should only take military action against Iraq if U.S. allies were in agreement (2002).

The constraining factors in the Campaign were public opinion, both domestic and international. The need for public support made it impossible for the Bush administration to attack Iraq without first developing and implementing a propaganda campaign. The power struggle was between the Bush administration, Saddam Hussein, and public support. At stake was American security, Iraqi lives, U.S. military lives, a positive public image for the president, and his chances of re-election in 2004.

Identification of the Propagandist

The propagandist in this Campaign did not hide; it was clearly the Bush administration. Since the president has ultimate say, he technically was the propagandist, but he used the various mouthpieces of his cabinet members and other leaders. The leaders of the U.S. lead coalition countries were also propagandists, predominately to their own people. However, the American population was also influenced by foreign propaganda that was covered in the U.S. Prime Minister Tony Blair is a good example. Part of the reason for raising a coalition and holding joint press conferences between President Bush and foreign leaders was to shift the focus off of the Campaign as being solely a U.S. effort and demonstrate that it was a united effort among coalition countries.

Structure of the Propaganda Organization

The executive branch of government is highly structured and centralized. All staff, either directly or indirectly, reports to the president, who is the ultimate decision maker and authority. The administration's strategies and goals are not usually available to the public, except as revealed by the administration. Within the administration, there may be differing views, but ultimately the president decides what will and will not be policy. The results of such decisions are what are usually presented to the public so that the message appears to be unified. On some occasions administration staff may give conflicting statements, but such circumstances are usually quickly clarified and smoothed out. The Whitehouse having its own press secretary that gives daily briefings to a Whitehouse press corps facilitates this.

The American public elects the president and vice president. The president then appoints his cabinet. Some of President Bush's cabinet members at the time of the campaign included: Secretary of State Powell, Defense Secretary Rumsfeld, Deputy Defense Secretary Wolfowitz, Attorney General Ashcroft, and Secretary of National Security Rice, Press Secretary among other department heads. These cabinet members often represented the face of the administration to the public. The Campaign made extensive use of various cabinet members who gave speeches and interviews in a variety of places and to a variety of audiences.

George W. Bush Cabinet 2008

The Target Audience

The target audience for the Campaign (domestic) was the American people, including congress, the media, and the voters. Within these groups are subgroups based upon age, gender, race, political ideology, and personal experiences. The Campaign strategy for reaching out to military veterans was different from reaching out to young adults. Both the message and the method of communication were tailored for each group. The president and his staff frequently spoke at small church groups, civic organizations, and schools in face-to-face encounters. Personal persuasion is quite effective and enthuses the listeners to spread the Campaign message. In addition, mass media usually covers such events, so it is double coverage for the Campaign. Pro administration opinion leaders, such as Rush Limbaugh and Republican congressional leadership, also brought the Campaign to the target audience. A third method of reaching the target audience was through friends, relatives, and religious institutions that promoted the Campaign. In many instances, such influence is more persuasive than persuasive attempts directly from the propagandist.

Media Utilization Techniques

Although the Bush administration did not have its own media outlets, the White House does have its own press corps, which makes media utilization very accessible and easy. On several occasions, the president requested media coverage to address the nation; mass media is generally inclined to provide coverage of presidential remarks. The news media was the best free publicity that the Campaign could have had. Surveys conducted by The Pew Research Center report that before the 9-11 attacks, the average number of people that followed the news very closely was only about 23 percent. By mid-September of 2001 that number jumped to 74 percent, which is greater than the public’s news interest in the 1992 Los Angeles riots and the end of the Gulf War (2001a). In March of 2003, before the war began, The Pew Research Center reported that 62 percent of the American public was very closely following the news about a possible war with Iraq (2003a). This means that 62 percent of the public would hear any propaganda that the Campaign disseminated through the news media.

The Campaign used mass media to reach specific subgroups of the target audience. One example of this was Collin Powell’s global MTV interview, where the possibility of war with Iraq was discussed (Powell, 2002, February 14). The Campaign also used radio to reach its audience, as was demonstrated by the president’s weekly radio addresses. Both the president and his cabinet reached the audience through televised speeches, television interviews (such as Meet the Press), and general news media coverage and editorials (newspaper, magazine, radio, television, and Internet).

The Whitehouse also has its own website, which is quite extensive and provides another mass media outlet to disseminate positive information (in both English and Spanish), including text, photos, and videos. The website also includes a webpage for The Office of Global Communications, which presents Whitehouse information and propaganda designed for a foreign audience. Even the president’s dog, “Barney the First Dog,” had a web page (Whitehouse, n.d.). The Whitehouse website also included an Iraq Homepage with the latest news and pictures from Iraq, including a “fact of the day” about Iraq and a complete archive on presidential remarks related to the Iraq campaign.

The campaign also made use of the printed media. One example is the detailed Whitehouse report, A Decade of Deception and Defiance (Whitehouse, 2002, September 12). This report outlines the Bush administration’s charges against Saddam Hussein and his regime.

Traditionally, people wear yellow ribbons in remembrance of missing people or military troops overseas. Yellow ribbons again became popular for troops involved in the War on Terror and for troops that went to Iraq. The ribbons kept the war in the people’s minds.

Churches are another means for the propagandist to reach the public. A March, 2003 survey by The Pew Research Center revealed that fifty-seven percent of the public that regularly attends religious services responded that their clergy had spoken about the possibility of war with Iraq. Thirty-four percent responded that their clergy expressed no position on the potential war, seven percent favored a war, and fourteen percent were against a war. Forty-one percent responded that their clergy did not speak about a war. The clergy of white evangelical Protestants rated highest in favor of a war, but only at fifteen percent. Black respondents reported that sixty-six percent of their clergy had spoken about a war, with thirty-eight percent speaking against a war and twenty-two percent giving no position. The majority of Catholic and mainline protestant respondents reported that their clergy either expressed no position about a war or did not speak about it (2003a).

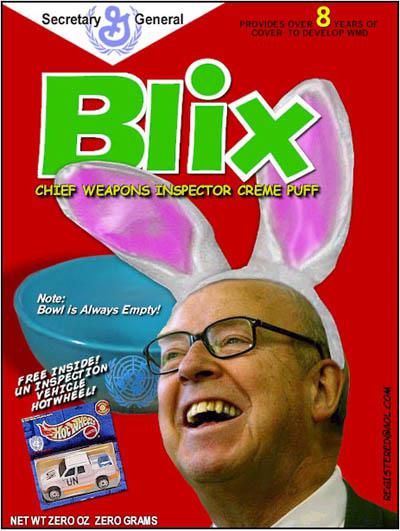

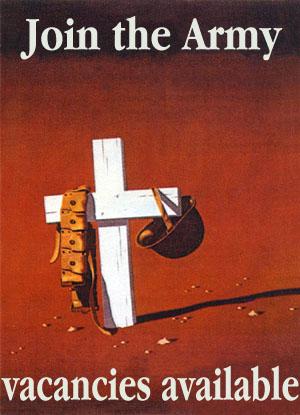

Both sides of the Iraq war issue utilized every form of media conceivable. Cartoon, manipulated photos, videos, songs, and poems both for and against the war were quite popular. Below are some examples of pro-Iraq war propaganda – although most likely not produced by the Campaign, they were still beneficial.

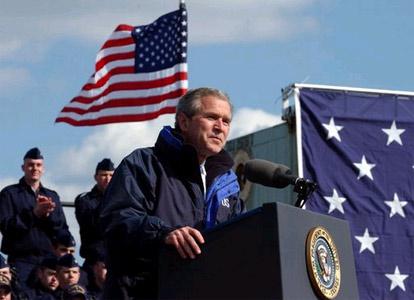

Special Techniques to Maximize Effect

A large portion of the target audience had predispositions with which the Campaign created a resonance, such as the common American desires for security, freedom, and democracy. Campaign messages related to these areas had the greatest impact on the audience. When the Campaign based its message on audience predispositions, it could interject new information that the audience often perceived as coming from within themselves (Jowett & O’Donnell, 1999). Examples of this include times when the president spoke about security, freedom, and democracy while linking it to the Campaign. The Campaign has also used this technique with visual graphics, such as backdrops for speakers.

Another technique that the Campaign used was to persuade the audience to like and identify with the propagandist (either the president or someone else speaking for the Campaign). By doing this, the audience would be more receptive to what the speaker has to say. This is one of Cialdini’s Weapons of Influence (2001).

One can see both techniques in the following photos. The backdrops seek to identify the president and his message with strength, security, and national pride – all ideas that the audience can readily identify with.

President Bush also used religious vocabulary to persuade certain groups, such as conservative evangelicals, to identify with him. Using a Google site search feature, the following religious words were found on the Whitehouse web site (www.whitehouse.gov). The vast majority of instances occurred in presidential remarks:

Word

| Number of Occurrences

|

|---|---|

God

| 1880

|

faith (not "faith based")

| 744

|

Evil

| 645

|

Church

| 448

|

Pray

| 198

|

Holy (not "holy land")

| 139

|

Mosque

| 117

|

Almighty God

| 105

|

Christ

| 49

|

Temple

| 47

|

Bible

| 42

|

Devil (not Kill Devil Hills)

| 32

|

Homosexual

| 15

|

Salvation (not army)

| 7

|

Righteousness

| 4

|

Heterosexual

| 2

|

Synagogue

| 0

|

On other occasions the president has used phrases or terms from the Christian bible that only Christians would recognize as having special meaning, such as in his 2003 State of the Union address where he said, “Yet there's power, wonder-working power, in the goodness and idealism and faith of the American people” (Bush, 2003, January 28). This is a quote from the Christian hymn, “There is Power in the Blood” (Jones, 1899), which refers to the power of the blood of Christ. On two occasions, he has used the phrase, “And the light shines in the darkness. And the darkness will not overcome it” (Bush, 2002, September 11; & Bush, 2001, December 22), which is a quote from John 1:5 in the Christian bible (New American Standard Bible (NASB), 1960). While speaking about the disaster of the Space Shuttle Columbia, the president quoted scripture saying, “In the words of the prophet Isaiah, ‘Lift your eyes and look to the heavens. Who created all these? He who brings out the starry hosts one by one and calls them each by name. Because of His great power and mighty strength, not one of them is missing’" (Bush, 2003, February 1). These are only a few of the many instances that President Bush has made references to Christianity during his public speeches.

Another influence technique is the “Low Ball for the Long Term” method (Cialdini, 2001, p. 89). In this strategy the persuader influences the audience using evidence that may not remain influential, but by that time the audience has already developed additional reasons to support the persuader, even if the first reason is negated. An example of this is the Campaign’s strategy to first link Iraq with terrorism. Since the target audience was already upset and desirous of revenge against the terrorist group responsible for 9-11, it was easy to gather support. Later, when evidence linking Iraq to terrorism came into question and was disproved, the target audience was already hooked and believed in the existence of WMD’s and the need to liberate the Iraqi people. The fact that their first evidence to support the Campaign was taken away did not sway their support.

The Campaign was also able to use the psychological principle of cognitive dissonance (Cialdini, 2001) by channeling the target audience’s publicly displayed nationalism and flag waving for support on the War on Terror into cognitive belief in and support for war against Iraq. Sometimes we change our beliefs to rationalize our actions. Two other methods of influence are also responsible for Campaign support. The “foolish fortress” is a defense against troubling thoughts and inconsistencies (Cialdini, 2001). Rallying around the flag, the president, and the war causes distraction from thinking about the evidence justifying a war as well as the reality of the consequences of war. Secondly, “social proof” is a powerful influence upon individuals (Cialdini, 2001). When public leaders, friends, and entire communities are publicly supporting the president and his call for war against a leader that almost everyone agrees is cruel, it is difficult to not follow the crowd. Each of these psychological principles of influence creates fertile ground for the propaganda Campaign.

Audience Reaction to Various Techniques

As mentioned, much of the public expresses their approval of the war by displaying American flags, patriotic or pro-war bumper stickers, yellow ribbons, etc. Many restaurants changed their menus removing “French fries” and replacing it with “freedom fries,” in protest to France’s opposition to the U.S. campaign to invade Iraq.

U.S. war propaganda was making headway by the fall of 2002. According to a survey by The Pew Research Center, by mid-September of 2002, 55 percent of the American public had thought “a great deal” about the possibility of a war against Iraq and 52 percent of the public believed that President Bush had presented a clear case for war Iraq. The month before, this number was only 37 percent. At this time, 64 percent of the public now favors taking military action (2002b).

Counterpropaganda

There exists a large amount of counterpropaganda to the Campaign. The antiwar campaign used demonstrations, politically left media, film (such as Fahrenheit 9/11), graffiti, and peacemaker teams. Many prominent congressional leaders, religious leaders, and Hollywood stars were used in the counterpropaganda campaign. The focus of the anti-propaganda campaign was on convincing the public that the real reason for war against Iraq was greed for oil. Other points were that the president mislead the public, which resulted in many deaths, and the administration’s supposed desire for blind obedience without dissent (a reflection of those opposed to the Patriot Act. Some of the antiwar political cartoons, posters, and bumper stickers are included below:

By early January 2003, the number of people believing that President Bush had made a clear case for war against Iraq had dropped to 42 percent. An important factor in the public’s opinion about going to war was whether the UN weapons inspectors found evidence of WMD’s. If the inspectors found weapons, 76 percent of the public would favor using military force against Iraq, but if the inspectors found nothing, public support for military action drops to 28 percent. However, 62 percent of the American public believes that the Bush administration has already determined to go to war (The Pew Research Center, 2003b).

Effects and Evaluation

The desired outcome for the Campaign was public support for an invasion of Iraq. How much support the president wanted before he decided to invade is not know. However, it is apparent that the Campaign raised enough public support that the president felt confident to go ahead with war plans. Since the commencement of the war the tables turned and the Campaign underwent several transformations. In the beginning, the propaganda campaign worked very well; however. setbacks in Iraq, along with high U.S. casualties and prisoner abuse scandals, caused the public to re-evaluate their support of the war. The president’s approval rating dropped to its lowest level. However, before invasion, the campaign was quite successful. This is evidenced by Congressional approval of military action against Iraq, public displays of support, and the public’s desire to support U.S. troops, which often results in supporting their cause. The campaign affected U.S. legislation, news content, the public’s mindset, and opinions. The use of major media was crucial to the success of this Campaign. The media has the power to support or discredit such campaigns. Without the propaganda Campaign and its use of media, it is doubtful that the public would have rallied around the president in support of war.

Survey

Were you in support of the U.S. invasion of Iraq?

Have you since changed your opinion about the U.S. invasion of Iraq?

References

About, Inc. (2004). We Shell Not Exxonerate Saddam [jpg image]. Retrieved on May 24, 2004, from http://politicalhumor.about.com/library/images/bliraqoil.htm

About, Inc. (n.d. a). Protest Parody [Jpeg image]. Retrieved on June 4, 2004, from http://politicalhumor.about.com/library/images/blpic-protestparody.htm

About, Inc. (n.d. b.). Fuck Iraq [Jpeg image]. Retrieved on June 4, 2004, from http://politicalhumor.about.com/library/images/bliraqaircraftcarrier.htm

About, Inc. (n.d. c.). Iraq France [Jpeg image]. Retrieved on June 4, 2004, from http://politicalhumor.about.com/library/images/bliraqfrancenext.htm

Boucher, R. (2002). International Criminal Court: Letter to UN Secretary General Kofi Annan. U.S. Department of State. Retrieved May 16, 2004, from http://www.state.gov/r/ pa/prs/ps/2002/9968.htm

Bush, G. W. (2001, September 20). Address to a Joint Session of Congress and the American People [transcript]. Office of the Whitehouse Press Secretary. Retrieved May 16, 2004, from http://www.whitehouse.gov/news/releases/2001/09/20010920-8.html

Bush, G. W. (2001, December 13). Remarks By the President on National Missile Defense [transcript].Office of the Whitehouse Press Secretary. Retrieved on May 16, 2004, from http://www.whitehouse.gov/news/ releases/ 2001/12/20011213-4.html

Bush, G.W. (2001, December 22). Radio Address by the President to the Nation [transcript]. Office of the Whitehouse Press Secretary. Retrieved on June 4, 2004, from http://www.whitehouse.gov/news/releases/2001/12/20011222-2.html

Bush, G. W. (2002, January 29). The President's State of the Union Address [transcript]. Office of the Whitehouse Press Secretary. Retrieved on May 17, 2004, from http://www.whitehouse.gov/news/ releases/ 2002/ 01/20020129-11.html

Bush, G.W. (2002, February 8). Remarks by the President at State of Utah Olympic Reception Rotunda, Utah State Capitol, Salt Lake City, Utah [transcript]. Office of the Whitehouse Press Secretary. Retrieved on May 31, 2004, from http://www.whitehouse.gov/ news/releases/2002/02/20020208-7.html

Bush, G.W. (2002, September 11). President’s Remarks to the Nation [transcript]. Office of the Whitehouse Press Secretary. Retrieved on June 4, 2004, from http://www.whitehouse.gov/news/releases/2002/09/20020911-3.html

Bush, G. W. (2002, September 26). Remarks by the President at John Cornyn for Senate Reception, the Hyatt Regency, Houston, TX [transcript]. Office of the Whitehouse Press Secretary. Retrieved on May 16, 2004, from http://www.whitehouse.gov/ news/releases/ 2002/09/20020926-17.html

Bush, G. W. (2002, October 2). Remarks by the President on Iraq, Cincinnati Museum Center - Cincinnati Union Terminal, Cincinnati, OH [transcript]. Office of the Whitehouse Press Secretary. Retrieved May 16, 2004, from http://www.whitehouse.gov/ news/releases/ 2002/10/20021007-8.html

Bush, G. W. (2003, January 28). President Delivers "State of the Union" [transcript]. Office of the Whitehouse Press Secretary. Retrieved May 16, 2004, from http://www.whitehouse.gov/ news/releases/2003/01/20030128-19.html

Bush, G.W. (2003, February 1). Remarks by the President on the Loss of Space Shuttle Columbia [transcript]. Office of the Whitehouse Press Secretary. Retrieved on June 4, 2004, from http://www.whitehouse.gov/news/releases/2003/02/20030201-2.html

Bush, G. W. (2003, February 9). Remarks by the President at the 2003 "Congress of Tomorrow" Republican Retreat Reception, The Greenbriar, White Sulphur Springs, WV [transcript]. Office of the Whitehouse Press Secretary. Retrieved May 17, 2004, from http://www.whitehouse.gov/news/releases/2003/02/20030209-1.html

Bush, G. W. (2003, February 13). Remarks by the President at Naval Station Mayport

Naval Station Mayport, Jacksonville, FL [transcript]. Office of the Whitehouse Press Secretary. Retrieved May 24, 2004, from http://www.whitehouse.gov/news/ releases/2003/02/20030213-3.html

Bush, G. W. (2003, February 26). President Calls for Action on Judicial Nominee, Presidential Hall, Dwight D. Eisenhower Executive Office Building [transcript]. Office of the Whitehouse Press Secretary. Retrieved May 17, 2004, from http://www.whitehouse.gov/ news/releases/2003/02/20030226-3.html

Bush, G.W. (2003, March 6). President George Bush Discusses Iraq in National Press Conference [transcript]. Office of the Whitehouse Press Secretary. Retrieved on May 16, 2004, from http://www.whitehouse.gov/news/releases/ 2003/03/20030306-8.html

Bush, G.W. (2003, March 16). President Bush: Monday "Moment of Truth" for World on Iraq [transcript]. Office of the Whitehouse Press Secretary. Retrieved May 16, 2004, from http://www.whitehouse.gov/news/releases/2003/03/20030316-3.html

Bush, G.W. (2003, March 17). President Says Saddam Hussein Must Leave Iraq Within 48 Hours [transcript]. Office of the Whitehouse Press Secretary. Retrieved May 22, 2004, from http://www.whitehouse.gov/news/releases/2003/03/20030317-7.html

Bush, G.W. (2003, November 19). Remarks by the President at Whitehall Palace Royal Banqueting House-Whitehall Palace, London, England [transcript]. Office of the Whitehouse Press Secretary. Retrieved on May 31, 2004, from http://www.whitehouse.gov/news/ releases/2003/11/20031119-1.html

Bush, G.W. (2003, December 16). Remarks by the President at Signing of the American Dream Downpayment Act, Department of Housing and Urban Development, Washington, D.C. [transcript]. Office of the Whitehouse Press Secretary. Retrieved on May 31, 2004, from http://www.whitehouse.gov/news/releases/2003/12/20031216-9.html

Cagle, D. (n.d.). White House LIES! [Political cartoon]. Retrieved on May 30, 2004, from http://politicalhumor.about.com/gi/dynamic/offsite.htm?site=http%3A%2F%2Fcagle.slate.msn.com%2F%2Fnews%2FIraq-LIES%2Fmain.asp

Cheney, R. (2002, August 29). Vice President Honors Veterans of Korean War [transcript]. Office of the Whitehouse Press Secretary. Retrieved on May 24, 2004, from http://www.whitehouse.gov/news/releases/2002/08/20020829-5.html

Cialdini, R. (2001). Influence: Science and Practice. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

CNN. (2001). Dismay as U.S. drops climate pact. CNN News. Retrieved on May 16, 2004, from http://www.cnn.com/2001/WORLD/europe/italy/03/29/environment.kyoto/

Fleisher, A. (2003, January 22). Press Gaggle Aboard Air Force One En Route St. Louis, MS [transcript]. Office of the Whitehouse Press Secretary. Retrieved on May 24, 2004 from http://www.whitehouse.gov/news/releases/2003/01/20030122-5.html

Fleisher, A. (2003, March 28). Press Briefing by Ari Fleisher, James S. Brady Press Briefing Room [transcript]. Office of the Whitehouse Press Secretary. Retrieved on May 24, 2004, from http://www.whitehouse.gov/news/releases/2003/03/20030328-4.html

GeorgeWBush.com. (n.d.) President at Mt. Rushmore. Retrieved on June 4, 2004, from http://www.georgewbush.com/HomelandSecurity/PhotoAlbum.aspx?gallery=17&page=2

GeorgeWBush.com (n.d.). Protect the Homeland [photo]. Retrieved on June 4, 2004, from http://www.georgewbush.com/HomelandSecurity/PhotoAlbum.aspx?gallery=17&page=2

GeorgeWBush.com. (n.d.). President at Port of Charleston, S.C. [photo]. Retrieved on June 4, 2004, from http://www.georgewbush.com/HomelandSecurity/ PhotoAlbum.aspx?gallery=17

GeorgeWBush.com. (n.d.). President in Pennsylvania [photo]. Retrieved on June 4, 2004, from http://www.georgewbush.com/HomelandSecurity/PhotoAlbum.aspx?gallery=17

Huck, G. (n.d.) Bushes Iraq Oil [Jpeg image]. Retrieved on May 30, 2004, from http://politicalhumor.about.com/library/images/blsaddamoil.htm

Irregulartimes. (n.d.). Antiwar Shop. Retrieved May 30, 2004, from http://irregulartimes.com/ antiwarshop.html

Jones, L. (1899). “There is Power in the Blood.” The Cyber Hymnal. Retrieved on June 4, 2004, from http://www.cyberhymnal.org/

Jowett, G. & O’Donnell, V. (1999). Propaganda and Persuasion. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

New American Standard Bible [electronic version]. (1960). The Lockman Foundation. Retrieved on June 4, 2004, from Bible Gateway, http://bible.gospelcom.net/

O’Neill, P. (2004, January 14). Inside Politics, O’Neill: Bush Planned Iraq Invasion Before 9/11. CNN. Retrieved on June 2, from http://www.cnn.com/2004/ALLPOLITICS/01/10/oneill.bush/index.html

Otteson, T. (2004). Syllabus: HUM203P-XCP, American Dreams: Four Major American Myths. Retrieved on May 24, 2004, from http://iml.umkc.edu/pace/Humn%20203P-w04.syl.pdf

Outraged Comics.com. (2004). Axis of Oil [jpg image]. About, Inc. Retrieved on May 24, 2004, from http://politicalhumor.about.com/library/images/blaxisofoil2.htm

Paul, M. (2004). I Want You [jpg image]. About, Inc. Retrieved on May 24, 2004, from http://politicalhumor.about.com/library/images/blcheneyunclesam.htm

Powell, C. (2002, February 14). Be Heard: An MTV Global Discussion with Colin Powel, Washington, D.C. [transcript]. U.S. Department of State. Retrieved on May 31, 2004 from, http://www.state.gov/secretary/rm/2002/8038.htm

Powell, C. (2002, March 27). Interview by Liane Hansen of National Public Radio [transcript]. U.S. Department of State. Retrieved on May 24, 2002 from, http://www.state.gov/ secretary/ rm/ 2002/9024.htm

Powell, C. (2003, April 22). Interview with Charlie Rose of PBS [transcript]. U.S. Department of State. Retrieved on May 16, 2004, from http://www.state.gov/secretary/ rm/2003/ 19816.htm

Registered@aol.com. (n.d.). Iraq Blix Cereal [Jpeg image]. Retrieved on June 4, 2004, from http://politicalhumor.about.com/library/images/bliraqblixtrix.htm

Rumsfeld, D. (2002, September 18). Testimony as Delivered by Secretary of Defense Donald H. Rumsfeld, Rayburn House Office Building, Washington, D.C. [transcript]. United States Department of Defense. Retrieved on May 24, 2004, from http://www.defenselink.mil/ speeches/ 2002/s20020918-secdef2.html

StrangeCosmos.com. (n.d.). Saddam Hear Me Now [Jpeg image]. Retrieved on June 4, from http://politicalhumor.about.com/library/images/blsaddamhearmenow.htm

The Pew Research Center. (2001). Terrorism Transforms News Interest. Washington, D.C.: author. Retrieved on May 17, 2004, from http://people-press.org/reports/display.php3?ReportID=146

The Pew Research Center. (2002a). Americans Favor Force in Iraq, Somalia, Sudan and …. Washington, D.C.: author. Retrieved on May 17, 2004, from http://people-press.org/ reports/display.php3?ReportID=148

The Pew Research Center. (2002b). Bush Engages and Persuades Public on Iraq. Washington, D.C: author. Retrieved May 17, 2004, from http://people-press.org/ reports/ display.php3?ReportID=161

The Pew Research Center. (2003a). Different Faiths, Different Messages. Washington, D.C.: author. Retrieved on May 17, 2004, from http://people-press.org/reports/ display.php3?ReportID=176

The Pew Research Center. (2003b). Public Wants Proof of Iraqi Weapons Programs. Washington, D.C.: author. Retrieved on May 17, 2004, from http://people-press.org/ reports/display.php3?ReportID=170

The Propaganda Remix Project. (2004a). We’ll Take Care of the Axis of Evil. About, Inc. Retrieved on May 24, 2004, from http://politicalhumor.about.com/library/images/ blpropaganda-soldier.htm

The Propaganda Remix Project. (2004b). No War for Oil [jpg image]. About, Inc. Retrieved on May 24, 2004, from http://politicalhumor.about.com/library/images/blpropaganda-suv.htm

The Propaganda Remix Project. (2004c). Join the Army: Vacancies Available [jpg image]. About, Inc. Retrieved on May 24, 2004, from http://homepage.mac.com/ leperous/PhotoAlbum1.html

Tyler, P. (2002, August 18). Officers Say U.S. Aided Iraq in War Despite Use of Gas. The New York Times, sec. 1, p. 1 [abstract, electronic version]. Retrieved on May 23, 2004, from http://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F20911FA38590C7B8DDDA10894DA404482

United Nations. (2004). Use of Sanctions Under Chapter VII of the UN Charter. Retrieved on May 17, 2004, from the Office of the Spokesman for the Secretary-General, http://www.un.org/News/ossg/iraq.htm

Washington Post. (2001, September 25-27). Washington Post Poll # 18439: Terrorist Attack, US Priorities. Philadelphia, PN: TNS Intersearch. Retrieved on May 23, 2004, from The Roper Center for Public Opinion Research, ftp://ropercenter.uconn.edu/ United_States/WashPost/USWASH2001-18439/version1/uswash2001-18439.pdf

Whitehouse. (2002, September 12). A Decade of Deception and Defiance. Office of the Whitehouse Press Secretary. Retrieved on June 4, 2004, from http://www.whitehouse.gov/news/releases/2002/09/20020912.html

Whitehouse. (n.d.). Barney. The Whitehouse. Retrieved on June 6, 2004, from http://www.whitehouse.gov/barney/

Wolfowitz, P. (2002, October 28). Remarks by Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz , Nashville, TN. [transcript]. United States Department of Defense. Retrieved on May 224, 2004, from http://www.defenselink.mil/speeches/2002/s20021028-depsecdef.html

Wolfowitz, P. (2003, Februaryy 23). Deputy Secretary Wolfowitz Town Hall Meeting with Iraqi-American Community [transcript]. United States Department of Defense. Retrieved on May 24, 2004, from http://www.defenselink.mil/news/ Feb2003/ t02272003_t0223ifd.html

Wolfowitz, P. (2003, May 9). Deputy Secretary Wolfowitz Interview with Sam Tannenhaus, Vanity Fair [transcript]. United States Department of Defense. Retrieved on May 16, 2004, from http://www.defenselink.mil/transcripts/2003/tr20030509-depsecdef0223.html

Worth1000.com. (n.d.). Saddam ZsaZsa [Jpeg image]. Author. Retrieved on June 6, 2004, from http://politicalhumor.about.com/library/images/blsaddamzsazsa.htm

© 2015 Rosa Malaga