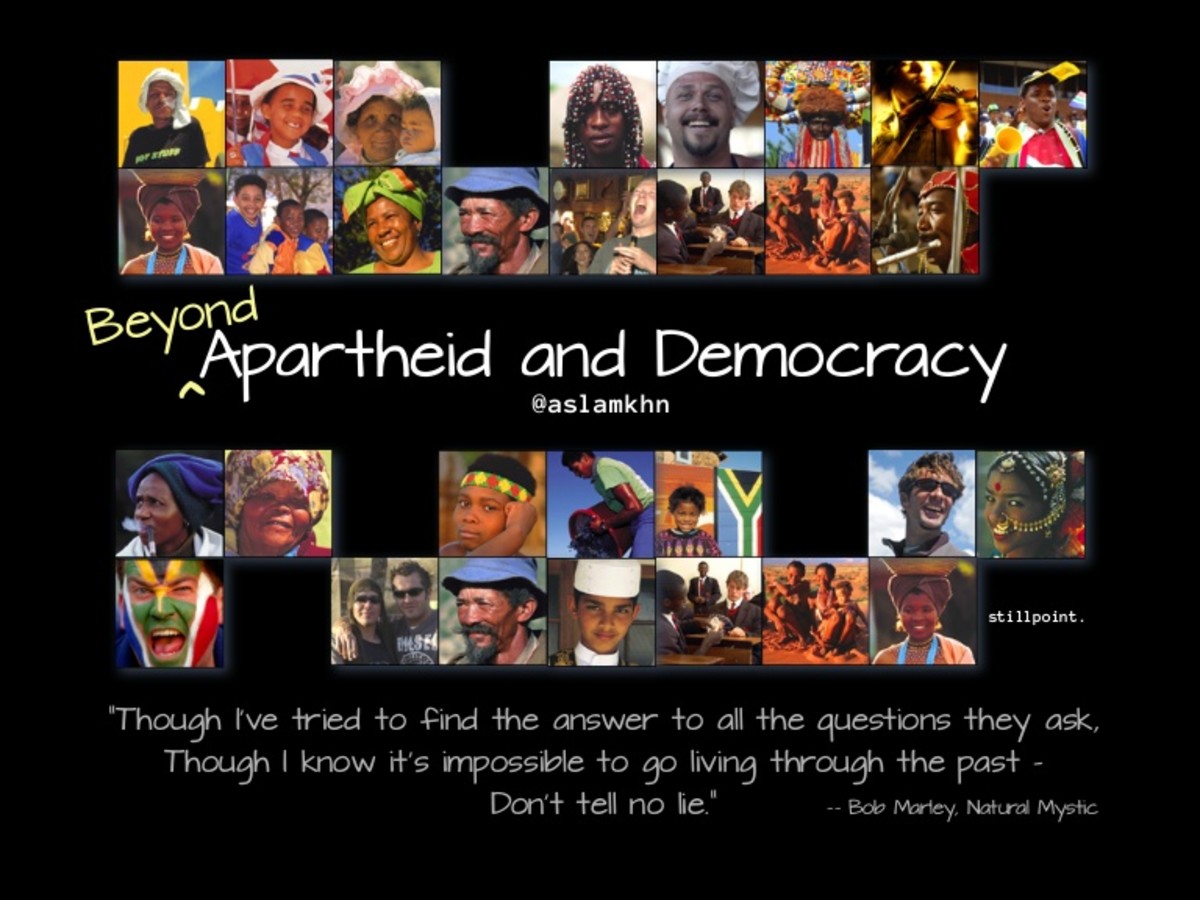

Apartheid's cruel legacy

The dawn of freedom

the bread i eat is crusted

tastes of a labourer's sweat

and a little flesh even

milk sours on my tongue

it curdles in my cupped hands

confutes my prayers

this day this earth will not accept

the mixing of my bones

with its holy soil

i crush the stone of despair

this land is agony, open my fist

find a rose gathering its blood from mine

- from shadows of a sun-darkened land by Shabbir Bhanoobhai (Raven Press, Johannesburg, 1984)

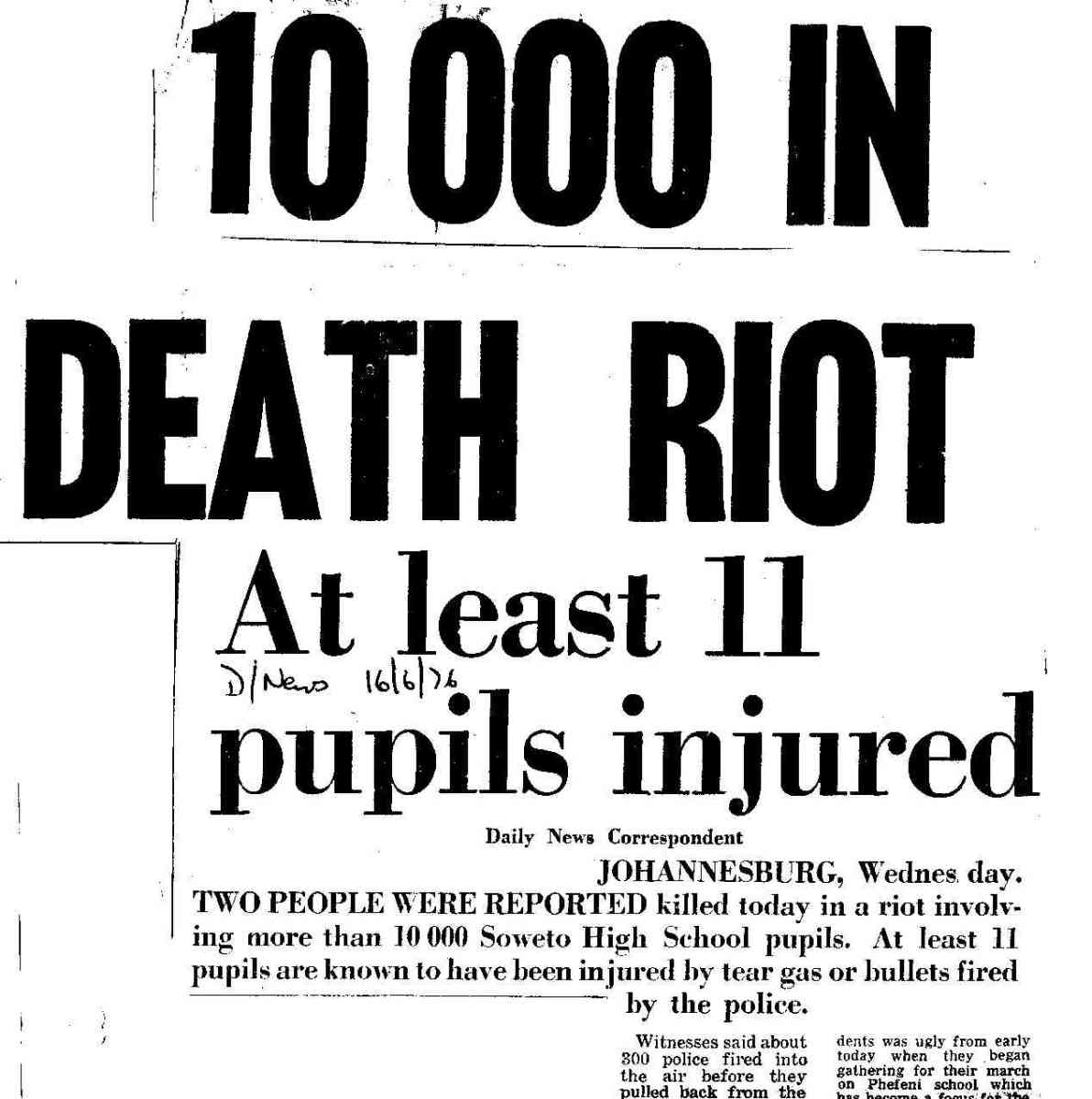

One day in February 1990 I listened with some colleagues to the radio as the then-president of South Africa, F.W. de Klerk, announced in Parliament what we had thought was impossible: the democratic formations banned since 1960 were being un-banned, the exiles were being allowed home, apartheid was officially dead. Even the man denounced by Margaret Thatcher as a "terrorist", Nelson Mandela, was to be freed. We didn't know whether to laugh or to cry - I think I did both. After more than 40 years the dreadful experiment in social engineering which had cost so many lives, so much pain, was over.

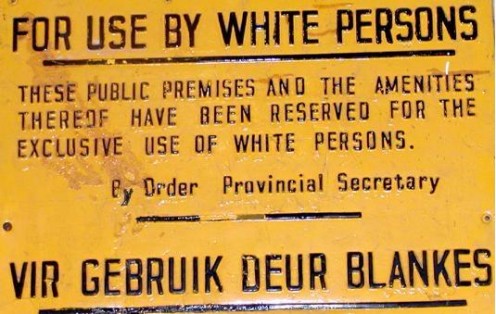

I say apartheid was officially dead, and so it was, but for the vast majority of people in South Africa all their lives had been lived under the terrible strictures of the evil policy and practice, and so the reality of apartheid in people's consciousness could not be taken away by one man's words, however brave; or by a decision of parliament, however real.

The stains and pains of apartheid live on now, even 19 years on. Too many lives were ruined by it, stunted and cramped by the hatred and fear, by the poor education and the differential treatment in hospitals and law courts, in housing and at work. We all of us still carry the scars, black and white, old and young.

David Webster

On that day in February 1990 I remembered those who had died in the struggle against apartheid, and I knew that their struggles, their pain and anguish, the cruelty they suffered, should not be forgotten in the joy of a new day of freedom.

I thought back to the day, not even a year before, when I had gotten the phone call from a friend - "David's been killed." That was 1 May 1989 and David Webster, academic and activist, had been shot while offloading plants from his car in front of his modest Johannesburg house. He and Maggie Friedman, his partner, had been to the plant nursery and had planned a planting day. Their plans were shot away by a cowardly member of the so-called "security forces" who shot and killed David from a moving car.

I had met David some years before when my ex-wife and he worked together, and we found we shared a deep love of music, especially South African jazz. We had just the week before been together listening to music and talking about the country and the people we both loved so much. We listened that evening to, among others, Bobby McFerrin, whose music I was just getting to know. David offered to make me a cassette tape of some of it, saying he would drop it by my wife's office when it was done.

The day after David's assassination my wife found the tape sitting on her desk, with a post-it note from David on it. I still have the cassette and the note. David had been round to the office the day before he was killed and left it there for me.

I thought back to the day a couple of years before that when my brother Chris was visiting and David was keen to meet him. David organised for us to go to see where Johnny Clegg participated in Zulu dancing every Sunday morning. Johnny was a good friend of David's - they worked together at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. So Chris and I drove to David's house to pick him up and went on to the place where Johnny would be dancing. There was this white man dressed in traditional Zulu fashion, dancing and speaking like a Zulu, and explaining to us the meaning of the moves and how he had learned them. Exactly what apartheid was designed to prevent.

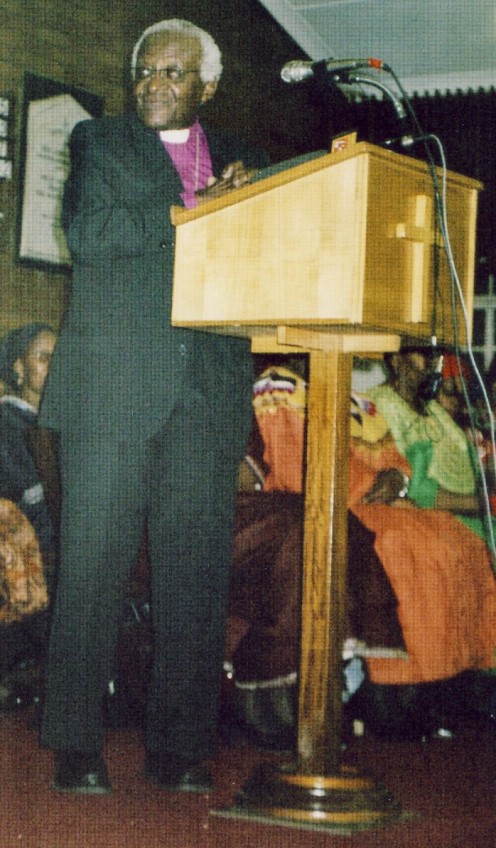

Desmond Mpilo Tutu

I thought back to the days when I worked at the South African Council of Churches, when Bishop (now Archbishop Emeritus) Desmond Mpilo Tutu was the General Secretary and where I came daily in touch with the agony caused by apartheid. I got to know Tutu as a beautiful person with a deep love of other people, an incredible sense of humour and an unshakeable belief in the ultimate triumph of the people over the ideology of apartheid.

And I saw how this gentle, but powerful man, threatened the minions of apartheid; how he, just by being who and what he was, made them feel defensive and therefore aggressive. How so many church people hated him. And I saw how it hurt him, how he suffered on account of it.

One day a group of these church people came into the offices of the Council and threw thirty coins onto the floor of Tutu's office, saying he was like Judas, betraying his country to the communists.

One of my most cherished memories of the time I worked with Tutu was the Holy Week retreat he took all the senior staff of the Council on one year. At the final liturgy of the retreat he asked all of us to stand in a circle and he knelt in the middle of the circle and asked us each individually to forgive him for his failings, for his mistakes. He asked us each to place our hands on his head and say we forgave him as he knelt there among us. I found it incredibly moving that this man, this wonderful person, could have such humility with us, who were technically his employees.

This was the man feared and hated by so many whites in South Africa at the time. Incredible.

Apartheid today

"Apartheid, to me, is a truly horrible political expedient because it is evolved by a people who know it to be unworthy, and who merely exemplify man's capacity for finding good reasons to do bad things." - Laurens van der Post in his 1965 Introduction to the William, Plomer novel Turbott Wolfe (the novel was first published in 1926).

These are just some of the memories of apartheid that came to my mind that day in 1990.

After that came the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), headed by Archbishop (he was by then Archbishop Emeritus of Cape Town) Tutu. And all the dreadful things started to come out, the horrors perpetrated by the apartheid goons, the suffering of the people, the disappearances, the killings, the beatings and torture. All the things done to keep the fiction of apartheid alive started to be made known to those who did not know them before.

And whites in South Africa were, many of them, completely unmoved by the revelations. The callousness bred by apartheid was too strong, or perhaps they could not bear to know the truth - we humans "cannot bear very much reality", I think. Besides, all these things happened to other people, other people we did not know, so how can they concern us? The revelations of the TRC showed, to those who would hear,

A world not world, but that which is not world,

Internal darkness, deprivation

And destitution of all property,

Dessication of the world of sense,

Evacuation of the world of fancy,

Inoperancy of the world of spirit

- from "Burnt Norton" by T.S. Eliot

That is the biggest part of the price that the dream of apartheid exacted from all of us - that we were held captive in chains we did not know, we were made sightless in a world of shadows and kept from knowing each other or ourselves by the power of a lie. And when the lie was exposed, we still struggled to comprehend the truth, because by now the truth seemed like a lie.

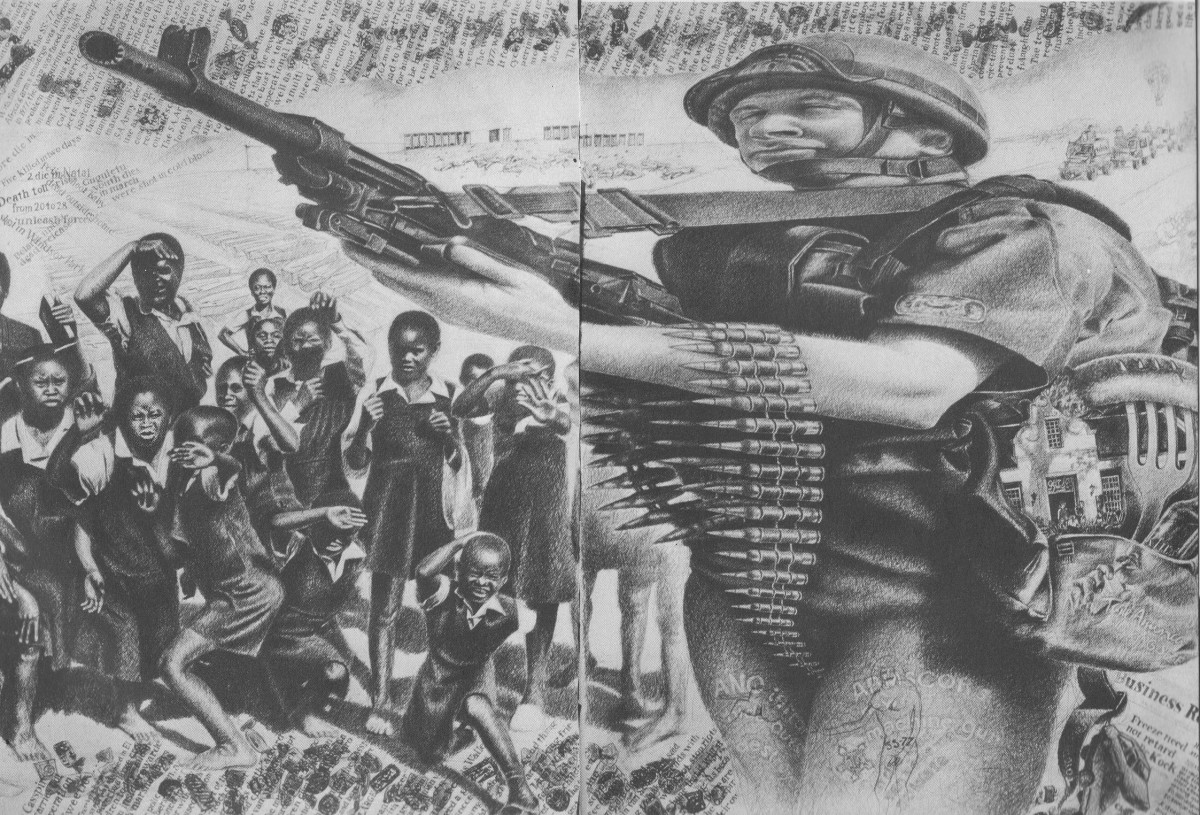

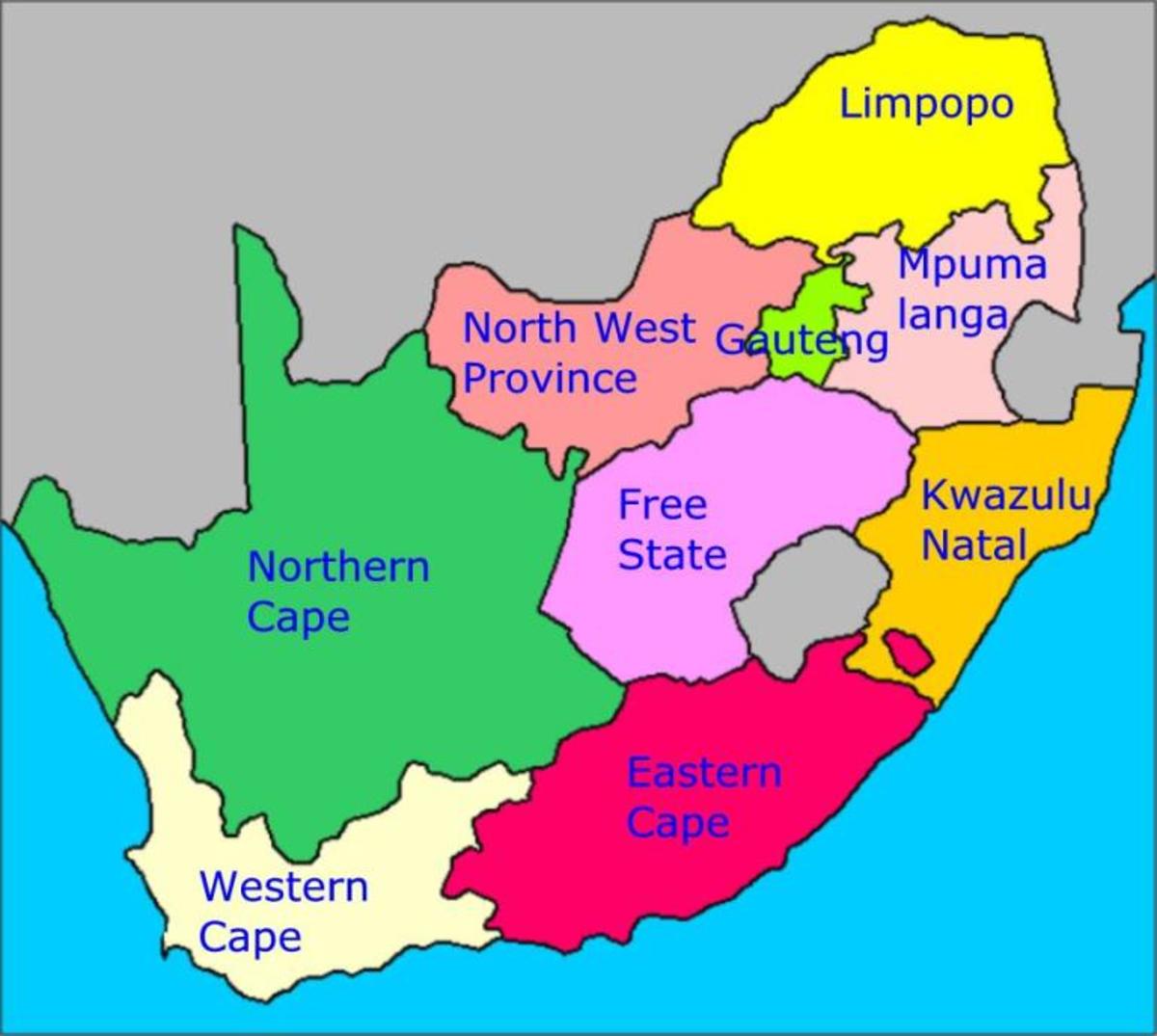

Millions of people were forced from their homes and dumped in places where they didn't want to be, so as to satisfy the drawing of lines between people.

People were forbidden to speak or to write, and so their wisdom was shattered in the hell of unknowing.

People were killed because they were nuisances, and were rocking the fictional security of the state.

And people were left unfeeling, cold, by the ultimate separation of the deaths of their neighbours.

And I keep wondering how long it will take the people to lose the scar tissue left by the wounds of apartheid. Because even those we call "born frees", those born after the democratic elections of 27 April 1994, are scarred by us, the survivors who were not born free, who compensate for our injuries by inflicting them on our children, even when we don't mean to or want to.

There are times, even now, when I am tempted by hopelessness, when the burden of the past seems too heavy, too much to carry in freedom. The scar tissue is too thick and unyielding to allow us to touch each other and to feel. And I see the works of hate still evident in the South Africa of 2009, the dreadful lack of mutual understanding still continuing.

Because the work of reconciliation is not done, and perhaps never will be.

But the challenge to us who love life is to keep the faith, to keep looking for ways to reconcile, to understand and have empathy for the other. Because it is only in finding the other, and giving the other the respect they are due, that we can find ourselves and give ourselves the respect we deserve.

And all shall be well and

All manner of thing shall be well

When the tongues of flame are in-folded

Into the crowned knot of fire

And the fire and the rose are one.

- from "Little Gidding" by T.S. Eliot

Copyright Notice

The text and all images on this page, unless otherwise indicated, are by Tony McGregor who hereby asserts his copyright on the material. Should you wish to use any of the text or images feel free to do so with proper attribution and, if possible, a link back to this page. Thank you.

© Tony McGregor 2009