As Volatile Midterms Approach, Five States Move to Make Elections "Hack-Proof"

Coming one step closer to citizens being able to verify the vote counts announced by the nation's election departments, a citizen's group has succeeded in obtaining a directive from the Florida Secretary of State, to local election officials, requiring them to preserve the digital ballot images in every race in which they are available.

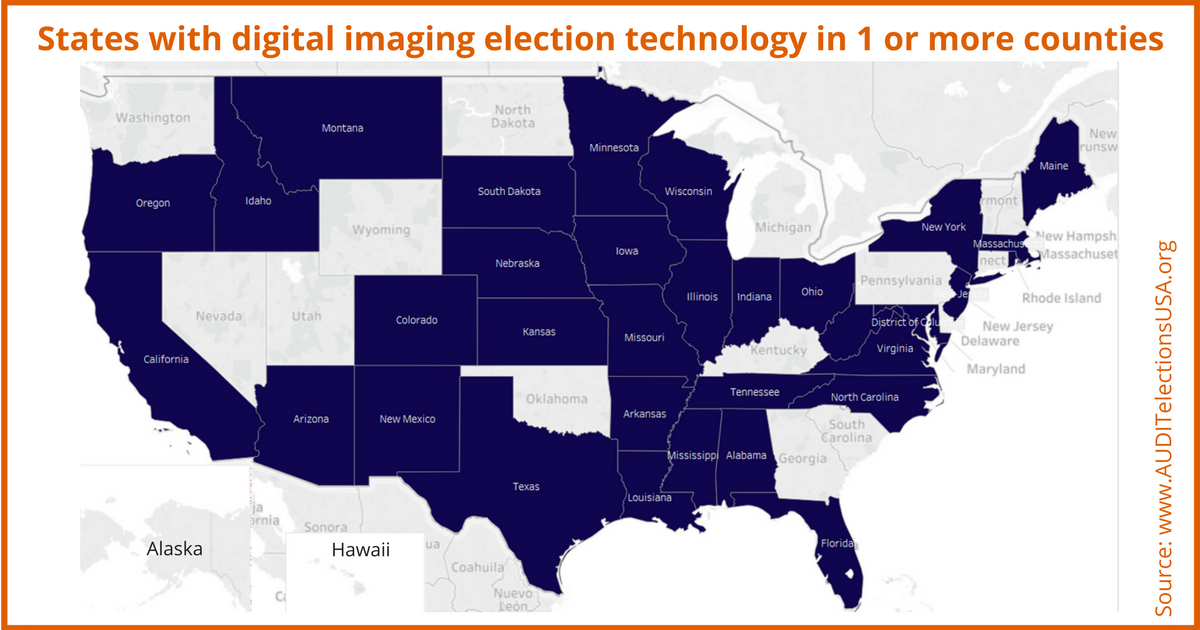

Ballot images are an audit feature present in about half of US voting precincts. They are images of voter hand-marked paper ballots, counted by state-of-the-art optical scan vote counting machines. Such systems are considered by transparency activists to be superior to any other technology from the standpoint of election security and transparency. (Counties which use vote-counting machines with ballot images feature.)

Modern optical scan vote counting machines are those which count the votes on voter hand-marked paper ballots using a technology which generates an instantaneous image of the paper ballot, and then stores it into machine memory. The images can then be used to verify an election department's announced election results, by posting them for examination by citizens. Any discrepancies which are found can be resolved by accessing and counting the votes on the actual paper ballots.

Florida now joins Ohio, Virginia, Arizona, and New York in having directives or court rulings in place directing local election authorities to preserve what has become a hot topic in election transparency circles: the ballot images.

Election transparency activists have repeatedly gone to court, in numerous states, to force election officials to preserve what the activists say are an integral part of the public voting record. So far most state courts have agreed, even though election departments have fought hard to keep the images from public view. Some officials have claimed the authority to destroy them outright. Federal law requires all official voting records to be preserved for 22 months after an election.

An attorney for the transparency activists, Chris Sautter, said, “We are very pleased, and we consider this another victory,” as reported by WhoWhatWhy.org.

In their quest to keep ballot images secret, election officials have argued that it would be possible to piece together a voter's identity "due to the nature of the choices." Transparency activists have called this argument preposterous.

Shrill warnings of Russian and even Chinese hackers fill the

news. Candidates and party activists like Senator Bernie Sanders nevertheless continue to urge citizens to march to the polls and vote, in an historic set of midterm elections, normally sleepy affairs, which will be seen as a referendum on the policies of President Donald J. Trump.

The contradiction between urging people to vote without those people having assurances that those votes will be properly counted has not been lost on everyone. In October 2016 the New York Times reported that fewer than half of Americans had confidence that their vote for president that year would be counted correctly, according to one study. Yet political campaign workers devote thousands of hours to phone banking, sign-holding, door-to-door campaigning, and other operations involving large expenditures of time, energy, and money to get the vote out.

Sanders has never commented on the accuracy of vote-counting in America, and conservatives tend to gravitate to a different kind of fraud, voter fraud, as a major source of cheating. Transparency activists say the greatest potential for cheating lies not in persons who vote who are not qualified to, but in the hacking of vote-counting machines in order to alter vote totals. While election officials argue that their machines are subject to "logic and accuracy" tests before an election, activists counter that these are meaningless, because it only takes minutes to hack into an election after these tests have been performed.

And while some election officials maintain that their systems are unhackable because they are not connected to the Internet, activists counter that nearly every election system is connected to the Internet at some point, even if just for the transmission of local vote totals via modem. Furthermore, they say, connection to the Internet is not necessary to access a vote-counting machine. The instructions for some vote-counting machines reside on removable memory cards. A maliciously hacked memory card can be swapped with a real one in seconds. In Fresno, California, election activists were aghast to learn that election workers would be taking vote-counting machines home for two days before an election, opening a gaping window for mischief.

Although the preservation and posting of the ballot images is not a foolproof, be-all-and-end-all solution to hacking, because hacking is soon exposed, it would make the hacking of elections many orders of magnitude more difficult than it is now. High-resolution images of paper are difficult to hack and fake, activists like John Brakey of Audit Elections USA say.

At the DefCon hacker's conference in 2017, hackers showed that they could break into some election systems in as little as 90 minutes. In 2018, the BBC reported on an election hacking competition for children, in which election systems were replicated resembling actual, functioning systems in the US. In the article entitled "Hacking the US mid-terms? It's child's play," the BBC reported:

The first competitor to break in was 11-year-old Audrey Jones. It took her 10 minutes. “The bugs in the code makes us [able] to do whatever we want,” she tells me. "We call somebody our own name if we want to, make it look like we won the election!”

Election transparency activists have been urging citizens across the country to demand that voter hand-marked paper ballots remain the defacto standard in every state, counted by optical scan vote-counting machines in which ballot images are generated and posted for public examination.