"But this has always been our home" - the pain of forced removal

From Tsarist Russia to South Africa

"But this corner of the world has always been our home. Why should we leave?" Tevye "I have some advice for you - get off my land!"

How many times in the history of the inhumanity of clearances, forced removals, ethnic cleansing or whatever it is called, has this cri de couer been heard, this anguished howl of pain from the heart?

I have just watched Norman Jewison's brilliant screen adaptation of the Broadway musical Fiddler on the Roof , and was incredibly moved by the scenes when the constable comes to tell the people of Anatevka in Tsarist Russia that they have three days to sell up their houses and property and leave. No alternative accommodation offered.

It was moving for me in that it is so reminiscent of the forced removals that happened in South Africa under the apartheid regime, which destroyed so many communities. among the more famous of the communities destroyed in South Africa were District 6 in Cape Town, Sophiatown in Johannesburg and Cato Manor in Durban.

In all some 3.5 million people were uprooted from their land and homes between 1948 and 1990, people who, like Tevye, could say "this has always been our home.

History and memory

Some could, like writer Bloke Modisane, in his autobiography Blame Me on History (1963), articulate the pain of the murder of a community: "Something in me died, a piece of me died, with the dying of Sophiatown; it was in the winter of 1958, the sky was a cold blue veil which had been immersed in a bleaching solution and then spread out against a concave, the blue filtering through, and tinted by, a powder screen of grey; the sun, like the moon of the day, gave off more light than heat, mocking me with its promise of warmth - a fixture against the grey-blue sky - a mirror deflecting the heat and concentrating upon my in my Sophiatown only a reflection."

A little later he describes the scene: "In the name of slum clearance they had brought the bulldozers and gored into her body, and for a brief moment, looking down Good Street, Sophiatown was like one of its own many victims; a man gored by the knives of Sophiatown, lying in the open gutters, a raising in the smelling drains, dying of multiple stab wounds, gaping wells gushing forth blood; the look of shock and bewilderment, of horror and incredulity, on the face of the dying man."

Another writer who experienced the horror of forced removals was Don Mattera who saw Sophiatown destroyed when he was still a young lad, and wrote about it in his autobiography Memory is the Weapon (1987): "The people moved and took with them all their broken dreams; all their high expectations and hopes and the fragments of things dear and prized. I looked on helplessly as many of my best friends, and my enemies too, boarded the army trucks with their families. they weaved and laughed mechanically - many were not aware of the full political implications of their exodus. Those who were cried uncontrollably as we kissed and hugged."

Mattera, like Modisane, felt that part of him died with the death of Sophiatown: "Something was dying inside of me; small and unnoticeable, but dying nonetheless. Perhaps it had something to do with the change and decay around me. Or the sweet memories that had gone with the twilight."

The people from Sophiatown were moved to a desolate area in the veld to the south of Johannesburg called, somewhat ironically, Meadowlands. As is so often the case in South African life a song was immediately written about this, Strike Vilakazi's "Meadowlands," which became a huge hit in South Africa and beyond.

The song, understood by the government to be in favour of the removals, was in fact an ironic protest against them. The song incorporates many of the resistance slogans used at the time of the struggle to prevent the destruction of Sophiatown: "Ons dak nie, ons polla hier (we are not leaving, we are staying here)".

These sound so much like the protests of the people of Anatevka: "We will defend ourselves. We won't go."

And that sad comment, "After a lifetime, a piece of paper, and get thee out," as one of the villagers remarks.

Note on the video- isn't it ironic that the only version of this song I can find on YouTube is by a white group from Australia? Huh!!!

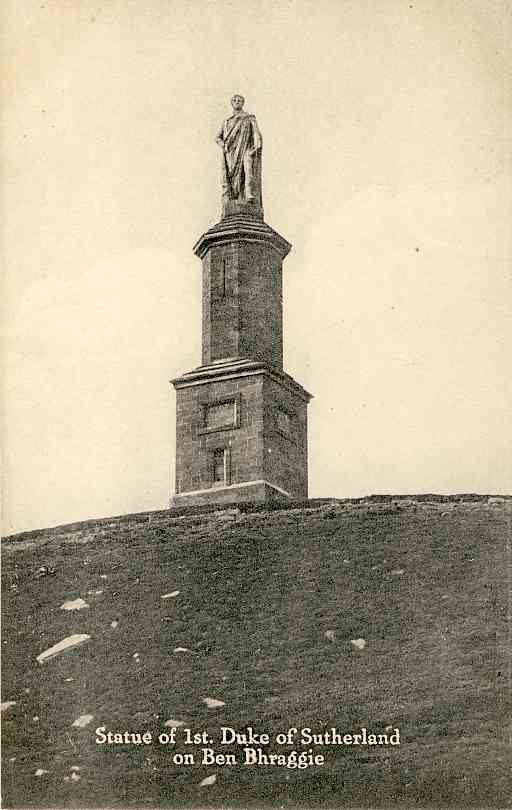

Highland clearances

This experience of forcible displacement was also the lot of many Scottish peasants in the 17th and 18th Centuries when the lairds decided to farm with sheep and so needed large grazing areas. To get these they threw people off the land they had been living on for generations, and these evictions were often achieved with extreme cruelty and with not regard for the wellbeing of those being moved. The remnants of their lives lie still all over Scotland in the form of the ruins of houses and villages.

One of the most notorious of the so-called "clearances" was that of the Sutherland estates in the decade from 1811 to 1821, during which some 15000 people were evicted from the homes they had occupied for generations, some of them being almost literally burnt out of their homes.

The significance of these clearances aroused in Karl Marx a degree of indignation that caused him to write in Chapter 27 of Das Kapital: "All their villages were destroyed and burnt, all their fields turned into pasturage. British soldiers enforced this eviction, and came to blows with the inhabitants. One old woman was burnt to death in the flames of the hut, which she refused to leave."

The result, as Marx noted, was that "In the year 1835 the 15 000 Gaels were already replaced by 131 000 sheep."

The horror continues

The eviction of people from their homes has many rationalisations - economic, racial, social, historical and even biblical. A report from news agency Reuters on 3 August 2009 told of the eviction of Palestinians from their homes in East Jerusalem: "Israeli police have evicted several Palestinian families from homes in Arab East Jerusalem and Jews have moved in, despite pressure from Israel's main ally, the United States, to freeze settlements."

The reason for these evictions? A court order based on land ownership claims in turn based on 19th Century documents.

And the violence of removals continues, according to the same report: "Police clad in black uniforms and carrying assault rifles cordoned off the area while the Palestinians' belongings were packed into removal vans."

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu asserted that Jews have a biblical right to live anywhere in Jerusalem.

And a Palestinian woman echoes Tevye in Fiddler : "This has always been my home."

And so it continues - people asserting their rights over other people's homes and livelihoods, and the pain is the same each time. Each time the people concerned are left with nothing but "sweet memories that had gone with the twilight." And the struggle to find themselves again in a new place, having to start all over again, with less than they had before.

Other stories of forced removals

- Cherokees in Georgia, the Rose and the Trail of Tears

There is a certain bent in some families to disregard and discredit one's ethnic roots. I call this the "Indian in the Cupboard" syndrome. My Great-Grandmother, Emma Sullivan was given Cherokee Papers to fill...