Comparing Vietnam to Iraq & Afghanistan

Check out my new book;

A revised version of this essay is included in my new American history book. If you click the link below, it will take you to a hub that provides more information. Or click the Amazon link to go straight to the Kindle Store where it can be purchased.

A classic Vietnam era anti-war song

Can "Humanitarian" Wars Be Won?

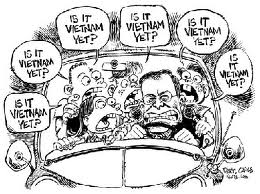

When it became clear that the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan were going to drag on for a while, the inevitable comparisons to Vietnam began. In some basic ways, however, the current wars bear little resemblance to Vietnam. The rugged terrains of Iraq and Afghanistan are nothing like the tropical rainforests of Vietnam. Insurgents in the current conflicts seem to have far less domestic and international support than the Vietcong once had, and they have not been organized as single, united forces. Also, the number of American deaths in Iraq and Afghanistan combined are only 1/10 (so far) of those killed in Vietnam.

Still, there are some eerie similarities. Like in Vietnam, The United States has been fighting against enemies who can be very difficult to locate and properly identify. These insurgents, like the Vietcong, recognize that they cannot take on the United States military in a “conventional” war. So they infiltrate communities, blend in with the civilian population, and are content to harass American soldiers (and the population in general) with quick hit-and-run strikes and booby traps. They know that they do not have to win in a conventional sense. They also know that when Americans kill civilians, it plays into the insurgents’ hands. So all that they need to do is inflict enough casualties and drag these conflicts out long enough to convince the United States that the costs are too high. In other words, they have to do the same thing that the Vietcong was able to accomplish.

This is why some would say that continued U.S. operations in Iraq and Afghanistan are ultimately pointless. Like Vietnam, these conflicts cannot be won. Others, however, disagree. Part of the reason that our efforts in Vietnam failed, they would argue, was that the American public did not adequately support the efforts of the military. And this lack of support went beyond the efforts of the liberal media and of those anti-war hippies. The federal government, partly out of fear of public opinion, asked the military to fight this war with “one hand tied behind its back.” For fear of inflicting excessive civilian casualties, soldiers could not root out and destroy communists as aggressively as necessary. Also, due to concerns about possible domestic and international reactions, restrictions were placed on bombing targets, with the North Vietnamese capital of Hanoi being a particularly important “off-limits” potential site. If enough of the public had recognized that “war is hell,” but you must fight to win, then the results may have been different. To those who maintain this view that Vietnam was winnable, history may be repeating itself in Iraq and Afghanistan.

I agree with those who say that lack of public support was a big part of America’s failure in Vietnam. Anti-war protestors, in fact, would take this as a compliment. In theory, it is also possible that more aggressive action could have led to a different result. This is assuming, of course, that over a half million troops, double the tonnage of explosives that were dropped in all of World War II, and the extensive use of chemical agents were just not enough. Still, there is an even more fundamental problem with this line of reasoning, a problem that also applies to the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. In Vietnam, the United States’ basic justification for involvement was to stop the spread of communism. Part of this effort, like the Cold War in general, was to protect and promote American interests. (A world full of communist nations, after all, is bad for business.) However, the United States also claimed that defending South Vietnam from communism would make that country a better place. So there was a humanitarian component to this war, a component that can lead to big trouble. After all, the more damage that the United States did in South Vietnam, the harder it was to argue that these efforts were helping the people of that nation. In a sense, the United States, through its stated policy objective, doomed itself to failure. At some point, the infliction of excessive death and destruction would make it impossible to declare any legitimate victory.

In World War II, the United States was not fighting against Japanese and German soldiers in an effort to make those countries better places. The goal was to defeat their military forces and destroy their capacity to continue fighting. World War II was unimaginably horrific, but it was also much simpler than a war like Vietnam. The enemy’s military forces were more easily identified, and the United States felt justified in targeting their civilian populations and using all of the firepower at its disposal.

The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan resemble Vietnam much more than World War II. In both places, like in Vietnam, the United States initially used national security as the justification for fighting. Afghanistan had terrorist training camps that were harbored by the Taliban government, and Saddam Hussein (supposedly) had “weapons of mass destruction.” Over time, however, particularly in Iraq, the United States justified its efforts with humanitarian language: liberation, promoting democracy, etc. Now, like in Vietnam, the United States is trying to win wars while appearing to help people, fighting against insurgents who are difficult to distinguish from civilians. With such unrealistic stated goals, it may already be impossible to ever declare victory.