Civil Disobedience, God's Call, and the Dream of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

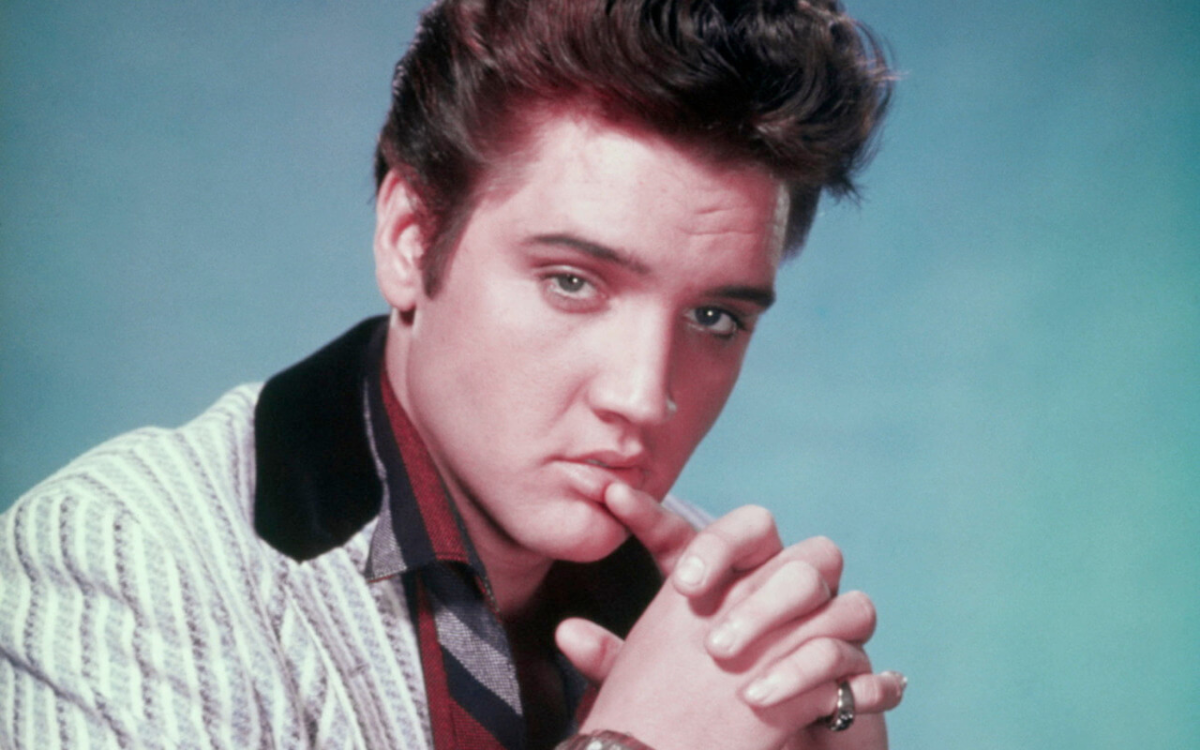

The Nonviolent Crusade of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

INTRODUCTION

The sixth chapter of the book of Daniel relays the events of one of the most well-known examples of civil disobedience found in biblical history. Daniel, a Jew living in Babylonian captivity, brazenly prays three times to Yahweh while refusing to submit to the self-centered decrees of King Darius. InBabylon, Daniel chose to stand up for his beliefs and did not turn his back on his convictions. The picture of American history is replete with images of men and women who, like Daniel, chose to stand up for their values and beliefs. Often these actions occurred in the form of civil disobedience.

Webster’s dictionary defines civil disobedience as “refusal to obey governmental demands or commands especially as nonviolent and usually a collective means of forcing concessions from the government.”[1] Perhaps no other social movement exudes the attributes of this classic definition of civil disobedience as the Civil Rights Movement. In his essay entitled “Civil Disobedience,” Henry David Thoreau writes “Unjust laws exist: shall we be content to obey them, or shall we endeavor to amend them, and obey them until we have succeeded, or shall we transgress them at once?”[2] Of course, Thoreau penned this question in 1849; however, African-American citizens living in theDeep South during the days of “Jim Crow” could relate to Thoreau’s sentiment. While citizens of a free country, Black Americans were not “free.” Instead, they were enslaved by a system that dehumanized African Americans by placing them at the back of the bus, in separate schools, and out of the white man’s sight.

One man would decide to take a stand against this type of injustice and become the leader of a movement designed to tear down the walls of racism and segregation. With a deep respect for the teachings of Jesus Christ and Mahatma Gandhi, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., became the prophetic voice of Black America. Dr. King preached a message of love and hope and expressed a desire for all humanity to live together in peace. His life was cut short by an assassin’s bullet, but Dr. King’s legacy lives on today. The following paper will look a the life and accomplishments of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. by examining the influence of such teachings as the Gandhian philosophy known as Satyagraha and the Social Gospel Movement upon Dr. King’s ministry. The paper will conclude with a critique of Dr. King’s Letter from Birmingham Jail and Declaration of Independence from the War in Vietnam -- two writings that evoke Dr. King’s passion for social justice and peace.

BEGINNINGS

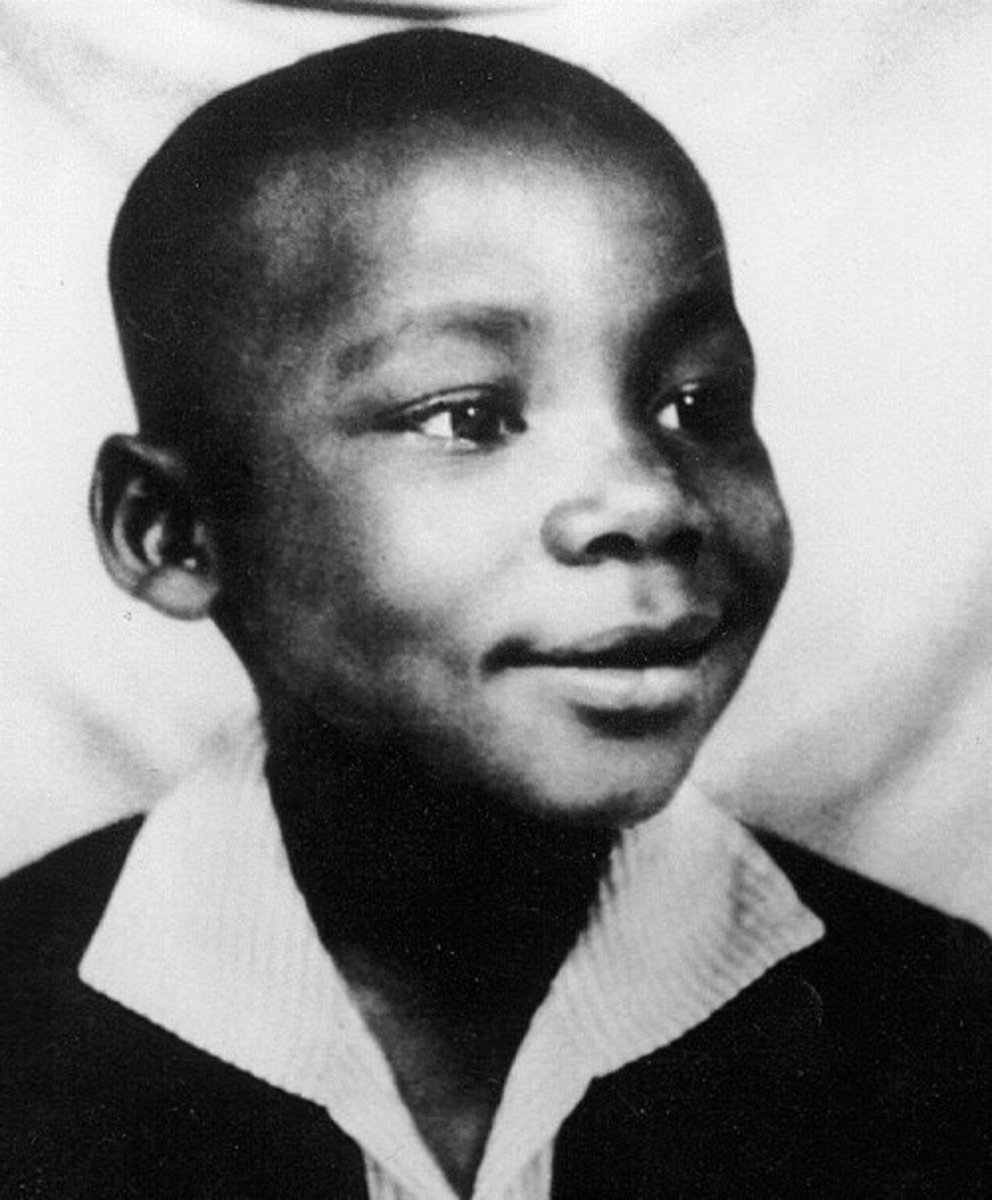

Michael (Martin) Luther King, Jr. was born on January 15, 1929, to Michael Luther King, Sr. and AlbertaWilliams King at the King family home in Atlanta, Georgia. In his autobiography, Dr. King states, “In my own life and in the life of a person who is seeking to be strong, you combine in your character antitheses strong marked. You are both militant and moderate; you are both idealistic and realistic. And I think that my strong determination for justice comes from the very strong dynamic personality of my father, and I would hope that the gentle aspect comes from a mother who is very gentle and sweet.”[3] Michael (Martin) King and his wife Alberta were instrumental in shaping the man who would lead a nation out of social captivity. King recalls his mother’s explanation of segregation to her young son. This was a discussion that plagued every Negro mother at that time. According to Dr. King, “My mother confronted the age-old problem of the Negro parent in America: how to explain discrimination and segregation to a small child. She taught me that I should feel a sense of ‘somebodiness’ but on the other hand I had to go out and face a system that stared me in the face every day saying you are ‘less than,’ your are ‘not equal to.’”[4] How does a young child learn to be somebody when society tells him that he is a second-class citizen? Dr. King internalized this question and struggled to understand how he could love a race of people that hated his very existence.

Dr. King deeply admired his father. Martin Luther King, Sr. was born the son of a sharecropper but possessed a desire to continue his education eventually becoming the minister of EbenezerBaptistChurch. Dr. King said the following of his father, “The thing that I admire most about my dad is his genuine Christian character. He is a man of real integrity, deeply committed to moral and ethical principles.”[5] From a social perspective, the King family was well-respected in the Black community. The family was prosperous, yet they were still Black. .

Dr. King joinedEbenezerBaptistChurchat the age of five. He fondly remembered the church as his “second home.” In Sunday school, he was taught lessons that were fundamentalist in nature; however, during his seminary years, Dr. King began to express a need to explore biblical criticism and liberal theology.

In 1948, King entered Crozer Theological Seminary after attending MorehouseCollege. Kings says of his years at seminary, “not until 1948, when I entered Crozer Theological Seminary in Chester, Pennsylvania, did I begin a serious intellectual quest for a method to eliminate social evil.”[6] According to one writer, “In his last year at seminary, King had found his belief in Rauschenbusch’s Social Gospel theology shaken to its roots by his first encounter with Nieburhr’s Christian Realism in classes taught by Kenneth Smith. Looking back on this crisis of his theological assumptions years later, King wrote: ‘Neibuhr helped me to recognize the complexity of man’s social involvement and the glaring reality of collective evil. Many pacifists, I felt, failed to see this.”[7] During these years, King struggled to understand God’s plan for his life; however, it was at this stage in King’s life that the young minister was exposed to the ideals that formed the building blocks of the Civil Rights Movement.

In 1950, King attended a lecture on Gandhi presented byHowardUniversitypresident Mordecai Johnson. King was attracted to Gandhi’s belief that oppression could be ended by the use of nonviolent protest. Years earlier, Gandhi had helped to freeIndiafrom British rule, and King believed that Gandhi’s approach could be most effective in the battle against segregation.

Ideas relating to the theory of nonviolent protest and pacifist beliefs were gaining popularity in American culture. Pacifist organizations were not new toAmerica. The Quakers or Society of Friends were known for their ardent stance against war. However, after the mass destruction caused by the detonation of the first atomic bomb,Americawas in shock. Pacifist ideas were starting to gain in popularity and educational institutions witnessed the emergence of a field of social study designed to create programs to facilitate the act of peaceful conflict resolution.

As previously noted, King was deeply influenced by the teachings of the Gandhian philosophy of conflict. This form of philosophy is also known as Satyagraha. The immediate purpose of Gandhi’s campaign was “to remove the prohibition upon the use by untouchables of roadways passing the temple” and the long-range goal could be defined as a “step towards ridding Hinduism of the ‘blot’ of untouchabilty’.”[8] King could see this same type of caste system inAmerica only the untouchables were not of Hindu decent. The untouchables inAmerica belonged to the Negro race, and the words of Gandhi’s teachings became King’s call to action

Gandhi wrote that “A Satyygrahi obeys the laws of society intelligently and of his own free will, because he considers it to be his sacred duty to do so. It is only when a person has thus obeyed the laws of society scrupulously that he is in a position to judge as to which particular rules are good and just and which unjust and iniquitous. Only then does the right accrue to him of the civil disobedience of certain laws in well-defined circumstances.”[9] King was certainly in a position to judge the unjust laws related to segregation. King states in his autobiography “My study of Gandhi convinced me that true pacifism is not nonresistance to evil, but nonviolent resistance to evil.”[10] King could see the importance of discerning between nonresistance and nonviolence. In order to conquer injustice, the community must gather together and demonstrate a united front against oppression. The key to wining the struggle could be found in active resistance. In King’s eyes there was much work to be done.

THE BIRTH OF A MOVEMENT

During his years at Crozer Seminary, King began to advocate a ‘preaching ministry’ devoted to ridding the world of injustice. In the words of Dr. King, “Above all, I see the preaching ministry as a dual process. On the one hand I must attempt to change the soul of individuals so that their societies may be changed. On the other I must attempt to change the societies so that the individual souls will have a change. Therefore, I must be concerned about unemployment, slums, and economic insecurity. I am a profound advocate of the social gospel.”[11]

From Crozer, King moved on to BostonUniversityto pursue a doctorate degree in Systematic Theology. In 1955, King received his doctorate. Two years earlier, King married Coretta Scott, the woman that would become his partner, advocate, and confidant during the movement. In 1954, King and his wife settled in Montgomery, Alabamaafter Dr. King accepted a call to pastor DexterAvenueBaptistChurch. Shortly after accepting the call, Dr. King joined the local branch of the NAACP. King says of his affiliation with the NAACP, “By attending most of the monthly meetings I was brought face-to-face with some of the racial problems that plagued the community, especially those involving the courts.”[12] Shortly after starting his work with the NAACP and the Alabama Council on Human Relations, the Montgomery Bus Boycott began.

On December 1, 1995, Mrs. Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a Montgomerybus to a white passenger. King said of Parks’ action, “One can never understand the action of Mrs. Parks until one realizes that eventually the cup of endurance runs over, and the human personality cries out, ‘I can’t take it no longer.’”[13] Parks action and subsequent arrest created a stir within the Black community. Eventually, Rev. L. Roy Bennett, President of Montgomery’s Interdenominational Alliance and minister of theMt.ZionA.M.E.Church, suggested the bus boycott.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott was important for several reasons. According to Marian Mollin, “The Montgomery Bus Boycott gave the nation notice that dissent was still possible and that organized nonviolence could be used effectively as a tool for social and political change.”[14] The boycott was successful and brought segregation from the Black perspective into the public arena. Now, Black society had something to say and a voice to say it with.

The boycott was designed with three major goals in mind. The committee passed a resolution stating that the Negro community would not resume riding the busses until white bus drivers promised courteous treatment towards Negro passengers; passengers were guaranteed seats on a first-come-first-serve basis regardless of race; and black bus divers were employed the run routes in predominately black neighborhoods.[15] King described the response to the boycott as nothing short of “tremendous;” however, success did not come to the protesters without a cost.

In order to maintain a means to get to work and move about town, 150 people signed up to drive Negro citizens around town at little or no cost to the passenger. In rebuttal, the Montgomerycity council passed legislation declaring all taxi services to charge a fee of $0.45 per ride.[16] This action put a damper on the volunteer cab service, but many individuals decided to cruise the streets randomly offering rides to black pedestrians. In addition to legislative obstacles, the participants suffered threats and even violence. Explosives were detonated in the homes of movement leaders including the home of Dr. King. However, not even incarceration could stop the determination to end segregation.

CARRY IT ON

As King and the Civil Rights Movement forged ahead, white activists jumped on the bandwagon. The struggle did not involve the Negro population, for now a few churches, humanitarian organizations and average citizens were engaged in the effort to end segregation.

In 1963, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., delivered his most famous speech. Today, this speech is remembered as “I Have a Dream.” Dr. King delivered this speech as he addressed the thousands of people gathered in WashingtonD.C.to show their support for the Civil Rights Movement. On that day, noted folk singer and peace activist, Joan Baez, stood by Dr. King. In her memoirs, she recalls that day by saying, “I was in Washingtonin 1963 when King gave his most famous speech: “I have a dream.” It was a mighty day, which has been described many times. I will only say that one of the medals which hangs over my own heart I awarded to myself for having been asked to sing that day. In the blistering sun, facing the original rainbow coalition, I led 350,000 people in ‘We Shall Overcome,” and I was near my beloved Dr. King when he put aside his prepared speech and let the breath of God thunder through him, and up over my head I saw freedom, and all around me I heard it ring.”[17]

In addition to participating in the March onWashingtonand the Children’s Crusade, Baez also attended church services led by Dr. King. She was not afraid to be seen in the midst of the Negro population. This act was a slap in the face to people who believed in segregation; however, the stigma was slowly beginning to disappear and freedom was on the horizon.

At one event, King made the statement, “We must hear the words of Jesus Christ echoing across the centuries: ‘love your enemies, bless them that curse you, and pray for them that despitefully use you.’”[18] Dr. King believed in his heart that these words were true, and he took the message to churches everywhere. The church members took these words to the public. The most significant aspect of King’s work in relation to religion inAmerica is that the Negro church was actively involved as a breeding ground for the movement. The idea to end segregation was conceived from the truth that can be found in the teachings of Jesus Christ.

On April 4, 1968, after years of protest and struggle, the bullet of an assassin claimed the life of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. On remembering the death of Dr. King, Joan Baez writes, “And now, as I write these pages about you, another nine years have passed, and I see that I still can’t say goodbye, and I see that it is not your flesh, but your spirit, and it is as alive for me today as it was when I sang you awake in the little room in Grenada, Mississippi.”[19] Although the bullet took his life, the spirit of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. could not be killed. It lives today, in the hearts of individuals who still work to protect human rights. Dr. King’s ministry teaches us that the most important thing that we can do to change people hearts is to demonstrate the love of Jesus Christ, a man who also loved the same people that took His life.

LETTER FROM BIRMINGHAM JAIL

Speaking out against injustice is not always supported by the masses. The struggle to end segregation was no exception. People wanted the issue to settle down, and like many times before, King was incarcerated for taking an active role in organizing a series of nonviolent protests in one of the South’s most racist cities--Birmingham, Alabama. Birminghamwas described as “a community in which human rights had been trampled on for so long that fear and oppression were as thick in its atmosphere as the smog from its factories.”[20] For years,Birmingham had suffered from the effects of white supremacy; however, cracks were forming in the power of the racist element within the city. Dr. King felt that it was the right time to take action.

In 1956, Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth had organized the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights. In his efforts to stop the injustice in Birmingham, Shuttlesworth and his wife were mobbed, beaten, stabbed, and jailed eight times in the name of freedom.[21] Actions by freedom fighters like Shuttlesworth were categorized as the actions of “troublemakers.” Racist politicians like commissioner of public safety, “Bull” Conner, and governor, George Wallace, vowed to keep the Negro in his place.

Believing that strength can truly be found in numbers, Dr. King, the SCLC, and the ACMHR designed a protest against Conner, Wallace, and the like in the spring of 1963. This plan simply known as “Project C,” brought the plight of the Birminghaminto the eyes of the public. The protest changed elections and it changed minds. The headlines of the Birmingham News on April 3, 1963, read “New Day Dawns for Birmingham.”[22]

All seemed to be going well until King and his associates were jailed for protesting unlawfully. Dr. King, however, was placed in solitary confinement. On April 12, 1963, eight clergymen representing the major faiths inAmericapleaded with King to end the movement. King responded to this request by writing a letter to the clergymen. King did not have a note pad or paper. Instead, he composed the letter on pieces of scrap paper given to him by other inmates. Today, this letter is simply known as “Letter from Birmingham Jail.”

The letter written by Dr. King answered the accusations that King and his counterparts were extremists and law breakers. Dr. King was hurt by these accusations. At times, King admitted that he did not feel that Church was supportive of the movement. In this letter, Dr. King, answers his accusers in his signature articulate and poignant style. He is jail, but he is not defeated. The letter reflects this attitude in an attempt to make his fellow clergymen understand the purpose for his actions.

King reminds his peers that he is in Birminghamto fight justice. He states, “Just as the prophets of the eight century B.C. left their villages and carried their ‘thus saith the Lord’ for beyond the boundaries of their hometowns, and just as the Apostle Paul left his village of Tarsus and carried the gospel of Jesus Christ to the far corners of the Greco-Roman world, so am I compelled to carry the gospel of freedom beyond my own hometown. Like Paul, I must constantly respond to the Macedonian call for aid.”[23] This writing like many of the other writings of Dr. King reminds the reader that God calls us to go to the masses. We may feel the pressure to succumb to the status quo, but we must persevere if we are to do God’s will.

King’s Birminghamletter is replete with the disturbing images of what it is like to be a Negro in America. The letter is obviously designed not to admonish is critics, but to educate these learned men about the unjust laws that fostered segregation. King states that it is his belief and that it is God’s will for the Church to be involved in the fight against segregation. He asserts, “But the judgment of God is upon the Church as never before. If today’s Church does not recapture the sacrificial spirit of the early Church, it will lose its authenticity, forfeit the loyalty of millions, and be dismissed as an irrelevant social club with not meaning for the twentieth century. Every day I meet young people whose disappointment with the Church has turned into outright disgust.”[24] These words may sound harsh, but Dr. believed in the necessity of Church involvement in the battle for Civil Rights. He only wanted other clergymen to feel the same.

DECLARATION OFINDEPENDENCEFROM THE WAR IN VIETNAM

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., will always be known for his courageous fight against segregation. More than just a leader of a social movement, Dr. King was a man of peace and took the time to address the issue ofAmerica’s involvement inVietnam. Like segregation, the Vietnam War was another controversial subject in 1960America. King and many of his fellow Americans believed thatAmericashould end the “police action” inVietnam.

The “Declaration of Independence from the War in Vietnam” was given by Dr. King in 1967 and this speech has become a classic piece of pacifist literature. In his discourse on war, Dr. King states “This is a calling that takes me beyond national allegiances, but even if it were not present I would yet have to live with the meaning of my commitment to the ministry of Jesus Christ. To Me the relationship of this ministry to the making of peace is so obvious that I sometimes marvel at those who ask me why I am speaking against the war.”[25] King takes the steps to remind his audience that the Good News is not just forAmerica. God’s message of salvation is intended for the communist, for the capitalist, for the Vietnamese, forNegros, and for Caucasians.

Jesus died for all of mankind; therefore, it is man’s obligation to live together in peace and not to harbor prejudice or malice against his neighbor. King also illustrates that black and white solders fight a united fight on the front line; however, they can not eat side by side in the same restaurant when they return home. This speech is not just a call to end the war, but to end all hatred and to end all violence.

CONCLUSION

Many people have called Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. a saint. Others have called him a savior, but he would probably argue vehemently against this moniker. Dr. King, however, demonstrated the importance of refusing to remain silent against injustice. Christ reminds us that what we do for the least of our brethren, we also do for Him. However, conservative churches seem to remain silent when they should speak out. Speaking out against injustice is not the duty of the liberals. Instead, it is the duty of the Christian. For in speaking out against injustice, we demonstrate the love of Jesus Christ. The Civil Rights Movement presented the American church with the opportunity to end a grave injustice. Instead of supporting Dr. King, many members of the clergy called for his silence. History tells us that ignoring a problem does not make it go away and to remain silent is not an option. As Dr. King predicted, many individuals have fallen out of favor with organized religion. Perhaps the American church needs a Third Great Awakening to rekindle her spirit and to understand the importance of what it means to do God’s work.

REFERENCES

Merriam Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary 10th ed. (Springfield: Merriam-Webster, Incorporated, 1994)

Henry David Thoreau “Civil Disobedience” The Power of Nonviolence: Writings by Advocates of Peace (Boston: Beacon Press, 2002)

Martin Luther King, Jr. The Autobiography of Martin Luther King Jr. Edited by Clayborne Carson. (Boston: Intellectual Properties Management, Inc., 1998)

James Tracy Direct Action: Radical Pacifism from the Union Eight to the Chicago Seven.

(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996).

Joan Bondurant “Satyagraha in Action” Nonviolence in Theory and Practice (Long Grove:

Waveland Press, Inc, 2005)

Mohandas K. Gandhi “On Satyagraha” Nonviolence in Theory and Practice (Long Grove:

Waveland Press, Inc, 2005)

Marian Mollin Radical Pacifism in Modern America: Egalitarianism and Protest. (Philadelphia:

University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006)

Lawrence S. Apsey “How Transforming Power Was Used in Modern Times” Nonviolence in

Theory and Practice (Long Grove: Waveland Press, Inc, 2005)

Joan Baez. And a Voice to Sing With: A Memoir (New York: New American Library, 1987)

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. “Declaration of Independence from the War in Vietnam” The Power

of Nonviolence: Writings by Advocates of Peace (Boston: Beacon Press, 2002)

[1] Merriam Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary 10th ed. (1994)Springfield: Merriam-Webster, Incorporated.

[2] Henry David Thoreau “Civil Disobedience” The Power of Nonviolence: Writings by Advocates of Peace (Boston: Beacon Press, 2002), 22.

[3] Martin Luther King, Jr. The Autobiography of Martin Luther King Jr. Edited by Clayborne Carson. (Boston: Intellectual Properties Management, Inc., 1998), 3.

[4] Ibid-King

[5] Ibid-King

[6] Ibid-King

[7] James Tracy Direct Action: Radical Pacifism from the Union Eight to theChicago Seven. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), 93.

[8] Joan Bondurant “Satyagraha in Action” Nonviolence in Theory and Practice (Long Grove: Waveland Press, Inc, 2005), 85.

[9] Mohandas K. Gandhi “On Satyagraha” Nonviolence in Theory and Practice (Long Grove: Waveland Press, Inc, 2005), 77.

[10] Ibid-King

[11] Ibid-King

[12] Ibid-King

[13] Ibid-King

[14] Marian Mollin Radical Pacifism in ModernAmerica: Egalitarianism and Protest. (Philadelphia: University ofPennsylvania Press, 2006), 78.

[15]Lawrence S. Apsey “How Transforming Power Was Used in Modern Times” Nonviolence in Theory and Practice (Long Grove: Waveland Press, Inc, 2005), 96.

[16] Ibid-King

[17] Joan Baez. And a Voice to Sing With : A Memoir (New York: New American Library, 1987), 103.

[18] Ibid-Aspey

[19] Ibid-Baez

[20] Ibid-King

[21] Ibid-King.

[22] Ibid-King

[23] Ibid-King

[24] Ibid-King

[25] Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. “Declaration ofIndependence from the War inVietnam” The Power of Nonviolence: Writings by Advocates of Peace (Boston: Beacon Press, 2002), 116.