2010 BP Gulf Oil Spill: Environmental Challenges and Dangers

The Gulf of Mexico's oil rig explosion on April 21, 2010, shows that off-shore drilling is not safe for workers or the environment. The fire is out and all workers but eleven were rescued, still as much as 336,000 gallons of crude oil a day could be rising from the sea floor 5,000 feet below. This represents a high risk for the Gulf coast environment. A turn in winds and currents might send oil towards the already endangered Louisiana's coastal wetlands, along with the present danger to the open sea creatures that inhabit the waters of the Gulf.

This is not the first industrial accident of this kind that occurs off-shore the United States. On January 29, 1969 a Union Oil Co. platform stationed six miles off the coast of Santa Barbara, California, suffered a blowout. For eleven days, oil workers struggled to cap the rupture, but 200,000 gallons of crude oil bubbled to the surface and were spread into a 800 square mile oil slick by winds and swells. Incoming tides brought the thick tar to beaches damaging 35 miles of coastline. The oil slick also moved south, polluting beaches on Santa Cruz, Santa Rosa and San Miguel Islands.

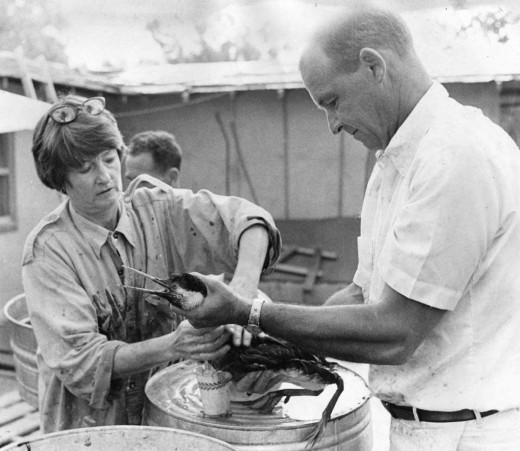

The disaster took a high toll on marine creatures... Incoming tides brought the corpses of dead seals and dolphins. Oil had clogged the blowholes of the dolphins, causing massive lung hemorrhages. Animals that ingested the oil were poisoned. Seabird population was also largely affected. Diving birds which must get their nourishment from the waters became soaked with tar and 3686 birds were estimated to have died because of contact with oil. Aerial surveys made on 1970 found only 200 grebes in an area that had previously drawn 4000 to 7000.

Hence, the 1969 experience in Santa Barbara, helps to understand the potential environmental damages of the Gulf coast's 2010 oil spill. In the particular case of Louisiana, the danger is not just real ii could be catastrophic given the ecological and economical importance, albeit fragile, Louisiana coastal wetlands.

About environmental disasters...

The Louisiana Coastal Wetlands

The USGS have established that the Louisiana coastal wetlands have been disappearing through land subsidence and erosion at an alarming rate of 25 to 35 square miles annually. Since 1930, over 1,800 square miles have been lost and it is estimated that an additional net loss of more than 500 square miles may occur by the year 2050. At this rate, Louisiana accounts for 80% of the nation’s coastal land loss, and it is among the highest land loss rates in the world. This land erosion and coastal loss exposes communities to damage from storm surges as Hurricanes Katrina and Rita demonstrated in 2005. In that year, hurricanes Katrina and Rita eliminated 217 square miles of coastal wetlands in two days, according with the US Corps of Engineers.

Several factors have caused this massive erosion of the coasts. Although important for the protection of the city and population of New Orleans, the levee system that was constructed for flood control on the Mississippi River, is one of reasons. Other reasons include land abatement from oil and gas extraction activity in the coastal area, erosion, and the rise in sea level.

The coastal wetlands, built by the deltaic processes of the Mississippi River, contain an remarkable diversity of habitats. Among them: narrow natural levee and beach ridges, expanses of forested swamps, and freshwater, brackish and saltwater marshes. These habitats are one of the nation’s most productive and important natural assets. According to the Louisiana Coastal Area Ecosystem Restoration Study, Louisiana’s coast is: at the end of the North American Central and Mississippi flyways for nearly 70 percent of the migrant ducks; also provides critical stopover habitat for neotropical migratory songbirds; a critical habitat for many species of water birds, and threatened and endangered species such as the endangered brown pelican, piping plover, and sea turtles; and vital for 95% of all marine species in the Gulf of Mexico, since they spend a part of their life cycle in this wetlands. Besides, most of the 100 active bald eagle nests in Louisiana are on the coast; 4 to 6 million ducks winter, and over 400,000 geese overwinter in Louisiana.

On the other hand, one of the most valuable functions of wetlands is their ability to filter sediments, nutrients, and chemical pollutants from the water which flows from land. Wetland plants are able to remove nitrogen and phosphorus from runoff water while other wetland plants help remove heavy metals, sewage, and pesticides, thus preventing them from doing further damage in the ecosystem.

Les Îles de Chandeleur

Les Îles de Chandeleur or Chandeleur Islands are a chain of uninhabited “barrier islands” (a coastal landform and a type of barrier system) approximately 50 miles (80 km) long, located in the Gulf of Mexico. They contours the easternmost point of the state of Louisiana and are a part of the Breton National Wildlife Refuge, which was established in 1904 through executive order of President Theodore Roosevelt.

Chandeleur Islands provides habitat for colonies of nesting wading birds and seabirds, as well as wintering shorebirds and waterfowl. Twenty-three species of seabirds and shorebirds frequently use the refuge, and 13 species nest on the various islands. The most abundant nesters are brown pelicans, laughing gulls, and royal, Caspian, and Sandwich terns. Redheads and lesser scaup account for the majority of waterfowl use. The islands are also an important migrating point for many birds on their way south.

Other wildlife species found on the refuge include nutria, rabbits, raccoons, and loggerhead sea turtles. On May 3, 31 turtles were found dead on the beaches of Pass Christian. Among them are Loggerheads, Leatherbacks and Kemp's Ridley – the most critically endangered species of sea turtle in the Gulf.

On May 5, the US Coast Guard confirmed for the first time oil had made its way past protective booms and was washing up on land. And the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) said oil was coming ashore all across the Chandeleur Islands. Freemason Island, the southernmost of the "back islands" of the Chandeleur chain, was the first to be hit by a sheen of oil. On May 7 pelicans, gannets and other birds covered in oil were found on the Chandeleur islands, the second oldest national wildlife refuge in the US and home to countless of endangered birds.

About the Gulf coast...

The Wetlands Habitats and the Economy

The vitality and richness of Louisiana coastal zone, makes this state one of the largest producers of commercial marine fish landings. More than 30 percent of the US's seafood comes from offshore Louisiana. In 2000, Louisiana produced about $300 million in fish landings, including shrimp, crabs, menhaden and other finfish. And statistics from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) show expenditures on recreational fishing in Louisiana to be nearly $897 million annually.

The most immediate concern associated with the Gulf of Mexico oil spill has been the seafood industry. Production of about 23 percent of that amount has been temporarily shut down by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration because of the oil spill. Although the majority of the state's fishing waters remain free of oil and open to fishing, the ongoing concern is that oil will make its way into estuaries. While fish can swim away from the impacted areas, the concerns are for oysters, shrimp and larvae that are unable to evacuate the spill.

Three weeks after the blowup, the tar had already affected other coastal areas and local economies in the Gulf. For instance, in Bayou La Batre, the heart of Alabama's seafood industry, the docks were largely quiet as thousands of shrimpers and seafood processors remained idled by fishing restrictions. And it is almost certain that the life cycle of shrimp in the Gulf will be affected by the spill. Shrimp reproduce and lay their eggs in the Gulf, which is now largely covered in dispersed and floating oil, and then move inshore to the estuaries, which are are also at risk. IN addition, about 30 oyster-processing plants have run out of product and shut down, putting as many as 900 people out of work.

The Mississippi Delta, Breton and Chandeleur Sound continue to be threatened by shoreline contacts. To the west of the Delta, the shoreline between Terrebonne Bay and Barataria Bay will be also threatened by Monday, May 10. Potential oil contacts could reach as far west as Pt Au Fer Island by May 12. For a projected trajectory of the oil spill go here.

Ocean Fresh

Ocean fresh clear and blue,

Crystal sand so pure.

Dolphins play here and there,

Jumping round through the air.

Turtles swim day and night,

Get stuck in bottle rings, what a fright.

There’s really no way to describe this place,

Hidden beneath its one big garbage waste.

Toxic waste oil spills,

Fishing line and plastic bags kill.

We can change what lies beneath,

No more whaling.

No more sleep,

Until we do something to change the big deep.

Once again the oceans so pure,

Leave it clean for people to endure.

© Clair Chick

The economic and ecological importance of Louisiana coastal wetlands to the U.S. and other coastal zones in the Gulf is enormous. It is a highly productive area and an important base of the United States' economy.

Louisiana's coastal wetlands and the Gulf coast resources and habitats should be protected for the future, the continuing extraction of oil from the seabed, not only endangers the environment, but also the economic future of the communities of the zone.

If you want to learn more about this topic, visit this websites: