Estonians, Nazis and Communists

A Small Country With a Complicated Past

Estonia has been in the news lately, accused of honoring Nazis and fueling Neo-Nazi sentiments. There's a lot more to it than that.

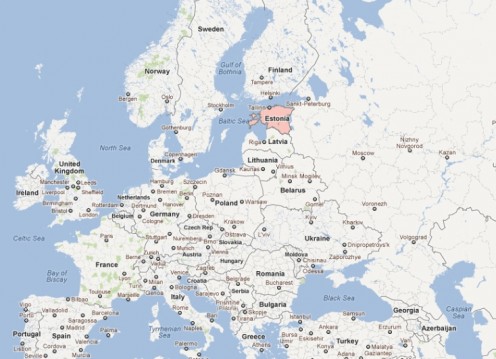

Estonia is a small country at the northeastern tip of Europe on the Baltic Sea. To the south is Latvia; to the east is Russia. It is slightly larger than Denmark, encompassing nearly 17,500 square miles, but its population of approximately 1.3 million people is much less. Estonia, whose capital is Tallinn (pop. 416,000), is now a full-fledged member of the European Union, NATO and the Eurozone, but the Twentieth Century was not kind to this nation, nor to her sister Baltic states, Latvia and Lithuania. The events the peoples of these countries have endured have weaved enormous internal as well as external complications into their lives.

1920 – 1939 Independence, Part I

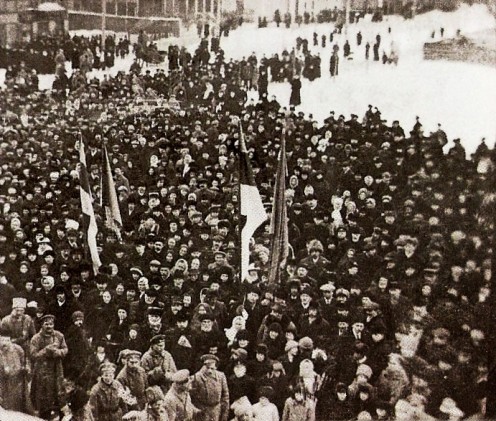

The modern state of Estonia was born from the ashes of the First World War. Having been part of the Russian Empire for two centuries, Estonians first declared their independence in February 1918 after the Russians retreated but were then occupied by the advancing Germans. After the Armistice of 11 November, 1918, Estonia fought a defensive war of independence against both the Soviet Red Army as well as mostly German troops that the Allies had insisted remain in the Baltic region to check the Red Army. The Estonian Liberation War lasted from 1918 until 1920, when the Tartu Peace Treaty was signed on 2 February, 1920. Estonia was finally an independent nation.

1940 – 1941 Communist Occupation and Deportations, Part I

Nineteen years later, when the Soviets and Germans signed their Non-Aggression Pact in 1939, the Baltic states were secretly “given” to the Soviet Union. Nine months after the start of World War II, on 16 June 1940, the Communists took their “gift”, invading Estonia with overwhelming force and beginning a brutal occupation. A year later, over a period of two days in June of 1941, about 10,000 Estonians, including 5,000 women and 2,500 children under the age of 16 were taken from their homes and deported, mostly to Siberia. Later that same month, Germany launched Operation Barbarossa against the Soviet Union and 34,000 Estonian men were forced to fight with the Red Army; more than 23,000 died.

1941 – 1944 Nazi Occupation and Genocide

When the Germans invaded Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania in June 1941, the Red Army retreated. Many Estonians at first looked upon the Germans as liberators from the repression they'd been living under. Then the Germans introduced their own brand of brutality. Einsatzgruppen, German mobile killing units tasked with cleansing occupied lands of undesirables, involved Estonian police units, the Omakaitse-- Estonia's “Home Guard” and other Estonians in their Final Solution. During the German occupation, 1,000 Estonian Jews, 250 Roma (also known as Gypsies) and 6,000 – 7,000 Christians were murdered. In addition, concentration camps were constructed on Estonian territory to hold other nationalities sent there by the Germans. Some 10,000 of those people also died, mainly Jews and Soviet prisoners of war. In 1944, as the Red Army approached, the Germans formed the 20th Waffen SS Grenadier Division (Estonian Nr 1) comprised of Estonian volunteers and conscripts and deployed them in the northern part of the Eastern Front to delay the Red Army. The division was mostly wiped out.

1944 – 1991 Communist Occupation and Deportations, Part II

In the autumn of 1944, the Soviets re-occupied Estonia. Immediately, 30,000 more Estonians were deported to Soviet labor camps. Continuous deportations, on a much smaller scale continued during the post-war years into the 1950s. On March 25, 1949, almost 21,000 more Estonians were deported to Siberia, half of them women and 6,000 children under the age of 16. To integrate Estonia and the other Baltic states more completely, the Soviets encouraged their own people to immigrate there, diluting the native populations with loyal Soviet citizens. They also militarized parts of the country, making large sections, especially the coasts, off limits to the native population.

War Crimes

The Nuremberg Trials had declared that, while the SS was a criminal organization (meaning its members were automatically war criminals), its conscripts (those who had no choice about joining) who had committed no war crimes were not considered war criminals.

In 1950, the US Displaced Persons Commission declared “The Baltic Waffen SS Units (Baltic Legions) are to be considered as separate and distinct in purpose, ideology, activities, and qualifications for membership from the German SS, and therefore the Commission holds them not to be a movement hostile to the Government of the United States.”

1991 Independence, Part II

With the weakening and eventual collapse of the Soviet Union, Estonians began again to work toward complete independence. Formal independence, reconstituting the pre-1940 state, was declared on 20 August 1991 and the Soviet Union recognized Estonia's independence in September of that same year. However, Russian troops were not completely withdrawn until 1994.

Today, Estonia, as small as it is, looks to be a success. It has weathered the recent recession, has a balanced budget, almost no debt and has a high income economy. It is in the forefront of high technology, with innovative e-services used for voting, census tracking and tax payments, among others. On the other hand, there are many echos of its grim past. Estonian is the only official language and its Russian-speaking minority feels excluded and discriminated against. For nearly 50 years, Estonians knew nothing else but Soviet domination. Charges of collaboration would therefore cast a fairly large net. Estonians fought on both sides during the war and so one faction will always gain at the expense of the other. Perhaps the proximity to the Russian bear and a half-century of sometimes brutal domination diminishes the horrific acts of the Nazis. The government insists it wishes only to recognize the sacrifices of those who fought for their homeland and has nothing to do with Nazism-- but Neo-Nazis see encouragement in such honorifics. Perhaps in time people can put aside their differences and come together but, without diminishing the absolute evil of the Holocaust, which would you have chosen-- if you even had the choice-- Hitler or Stalin?