European Crisis on "NATO"

The criticism of French President Emmanuel Macron about the performance of NATO renewed the debate about the meaning of “Atlanticism” today for European countries, as well as for the future of the alliance. In an interview with the Economist weekly entitled: "Europe: NATO enters into a state of clinical death" on November 7, Macron considered that "NATO" is in the stage of "brain death", criticizing the absence of "coordination in making strategic decisions between states" United and other partners in the alliance, "pointing out that" we are witnessing aggression by a state in the alliance, which is Turkey, in a region where we have threatened interests, without any coordination with us". Even if this change in the French dialect does not necessarily express a 180-degree turnaround in Paris's approach to transatlantic relations, it does point to a realistic trend which sees building a European defense policy as a vital necessity in the current context.

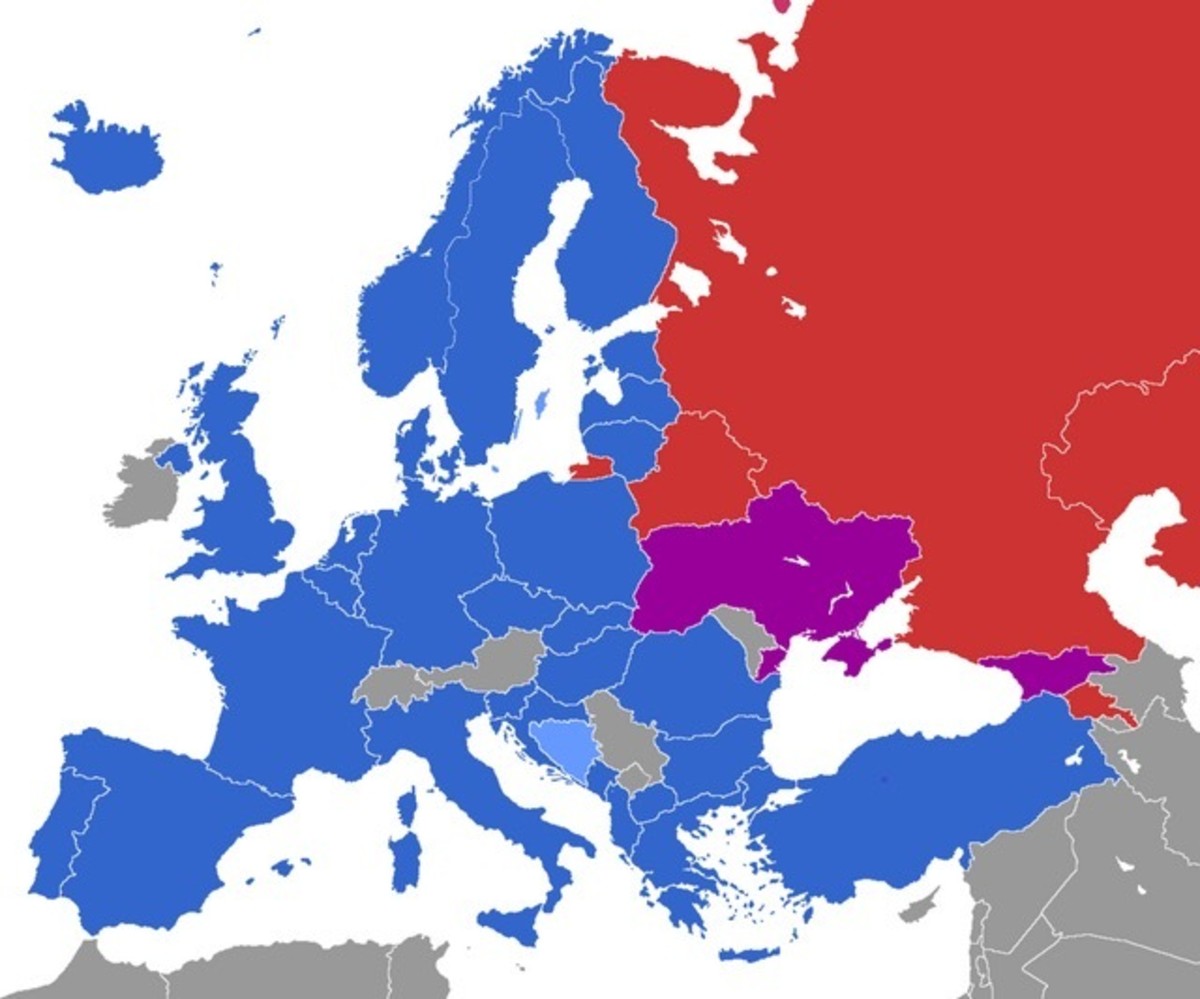

The creation of the "NATO" in 1949, and the extension of the US nuclear umbrella over Europe, reinforced the feeling of European security. Washington has obtained a mandate from the allies to adopt policies that serve, at least in theory, its common interests with its allies, but the increase in international conflicts and asymmetric threats in recent years is prompting a reconsideration of the importance of the role of NATO, centered exclusively on Russia. There is no doubt that Donald Trump's rise to power contributed to the weakening of the pluralistic international system inherited from the post-World War II era, and to paralyzing the tools he used to manage international crises. When he was a candidate for the presidential elections in March 2016, Trump announced that NATO had become expired and demanded that strategic burdens be shared with the Europeans by increasing their financial contributions to the alliance, and he repeated the same position in 2017.

These contradictory American statements led to a rediscovery of reality by France. After joining the joint leadership of the alliance in 2008, it considered that the European Union should develop its own self-defense capabilities, because any external protection cannot be eternal. But reviving the European defense project raises a deep divide between the countries of the Union: Germany is hesitant because of a political tradition that tends to oppose the development of military capabilities, and to be satisfied with the capabilities available to defend the lands of European countries. German Chancellor Angela Merkel did not hesitate to respond to Macron's words about "NATO", which she saw hastening and indiscriminate, reflecting the differentiation in attitudes toward the American ally.

The United States has succeeded in the past years in using "NATO" effectively, not for strategic goals, but to enhance customer relations on the political, economic and financial levels between them and small European countries such as Croatia, Bulgaria, Poland, and the Baltic states, all of which want to maintain the closest relations with Washington. There is no doubt that the caution of several European countries about what they see as a tendency to dominate in French foreign policy, since the founding of the Fifth Republic, weakens attempts to build a common European foreign and defense policy. The difficulty of defining common interests among the Member States of the Union is an additional obstacle to these attempts. However, Macron's speech may re-ask the question about the institutional form required for European construction: Does the Union constitute a grouping of sovereign states that each have their own diplomacy and national defense policy, or is it a federation with a joint government with sovereign powers?