Two American statesmen

Both came at distinct periods in American diplomacy, one heralding the period of détente, a movement to thaw the Cold War, another at the end of the Cold War, dismantling of the Soviet bloc, Soviet Union and the heralding of American hegemony and globalization.

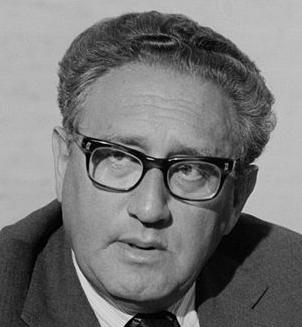

Dr Henry Kissinger and recently deceased (17 March, 2011) Warren Christopher both serving as Secretary of States, exhibited unlike characteristics at a period when America was trying to rule the global waves, first as an antagonist to the then Soviet Union and then as a single super-power in a unilateral world.

It was the periods of the 1970s and of the 1990s; it was first the period of American involvement in Vietnam and later Washington's involvement in the war against Iraq in 1991 when Washing sought to get Saddam Hussein out of Kuwait, which his country had invaded the previous August.

Warren Christopher served as Secretary of State in the Clinton administration from 1993 till 1997 when he retired from politics and diplomacy for good, despite brief stints. But he was a Secretary of State when there was great global entanglements as well as opportunities such as the peace process in the Middle East.

A number of people may have thought that he was not the right man for the job because of his demeanor. He was soft spoke, elegant, cordial, a man with boundless intellect, perhaps not the man required for the greasy world of international politics, where diplomats needed to adopt an aggressive style, a hard façade to be able to dictate, iron out and tune the best of foreign policy available.

Originally trained as a lawyer, he had been in domestic politics since the late 1950s and served in different administrations in the 1960s including as Assistant Secretary of State in the Jimmy Carter administration in the 1970s. When he wasn’t in politics, he was practicing law in O'Melveny & Myers, where he became a partner in 1958.

To his friends, he was a unique and special person as said by Larry Kramer, dean of the Stanford University’s Law School, the establishment he g raduated from. Kramer called him “brilliant”, “thoughtful”, “generous”, “modest and unselfish”. You can’t much more praise to know that he was a nice person.

Other people said of him he was courtly and reserved, methodical and self-effacing who worked very hard and travelled long miles to achieve foreign policy objectives. By the end of 1996, shortly before he was to retire, and now in his 1970s, he flown 704,487 miles on his air force plane. This suggests as will that he was a tough person but that his style was different.

He was a committed diplomat, travelling from one end of the globe, from China, Middle East and Europe, in search of the illusive concept called peace, in spite of the fact that the Clinton administration was now basically implementing the UN embargo regime that was imposed on Iraq shortly after the 1991 to contain Saddam Hussein, which harmed much more Iraqis than the former president who was subsequently hanged, 16 years later.

Christopher resigned the following year to be replaced by Madeleine Albright. President Bill Clinton said Mr Christopher had "left the mark of his hand on history", although he had his detractors, including those officials in the State Department who saw him as indecisive, and probably too weak for not making his point across effectively, clearly and with force. He was criticized by many for following policy rather than in helping to formulate and draw up strategy, being viewed as a man who would implement whatever was on the table, rather than come up with a grand design despite his commitment.

He was much different in persona than Henry Kissinger who served in the Nixon administration in the late 1960s, early 1970s. He was seen as a man of charisma, had bombastic character, someone with flair, a professor of politics and international relations who was interested in the affairs of nations, and their relations with each other. He studied hard theory, concentrating on the power of the strong, and wanted to put that into practice when he came to the State Department.

Some of his biographers explain that once he became Secretary of State, he closed all doors on the president, making himself as the “gate-keeper” where policy papers, decisions, suggestion to Richard Nixon had to go through throw him first. This created friction, but he didn’t care.

Christopher was seen by some, a comment probably made unkindly, as Clinton’s lawyer, following orders rather than making them or having a hand in them. This is in spite of his wide travels to China (US officials upset saying he wasn’t tough enough with the Chinese), Middle East, and of his credit in achieving the Dayton Accord in 1995 ending the fratricidal war in Bosnia.

His mannerisms of wanting to listen more rather than talk was viewed more as of placidity rather than shrewdness, and as tactics, despite the fact he was the force behind the freeing of the 52 Americans who had been taken hostages following the Iranian Revolution of 1978 at the US Embassy in Tehran.

As opposed, Kissinger was seen as a strategist who wanted to play hard ball in international relations and global politics. He also travelled much but it was interest based on the notion of power politics or politics of the strong he wanted to achieve vis-a-vis, a motley of different nations in the world including Europe, Russia, China, and of course the Middle East.

It was in the area of the latter region, Kissinger wanted to make his mark, not necessarily to achieve a deal but make sure what is best for America, and how he saw the world. Patrick Seal, a 1980s biographer of now the late Syria President Hafez Al Asad, argued in his “shuttle diplomacy” between Cairo, Damascus and Tel Aviv, Kissinger never sought to play the role of an “honest broker”, but pitied one leader against each other.

He loved the shuttle earning the name of "the professional traveler of the year" in 1973, playing a role that he long taught in theory and strategy. But whatever the case both personalities exuberated and espoused different styles of diplomacy that went for linking domestic politics with foreign policy, and one was outward, the other inward.