Faith-Based Outreach Initiatives and Programs - An examination of effectiveness

A Process and Outcome Evaluation of a Faith-based Social

Service Program

by Matt Anselmi and James Griffith Phd

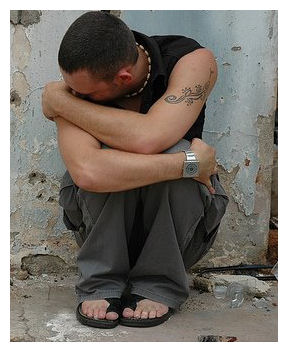

Although the outstretched hand of the poor remains the same yesterday as today, the faces of those who strive to fill those hands have taken on a new demeanor. Congregations and faith-based organizations have long been instrumental in delivering spiritual and temporal care to individuals living in or within the range of poverty. The scope of their reach, however, has been somewhat limited by the available funding, predominantly volunteer staff, and constrained materials that can be mustered by the members that labor tirelessly to meet the needs of an endless stream of poor and disenfranchised individuals. Despite this concerted effort, the poor remain poor.

While experiencing a devolution of welfare assistance from the United States government, it is not surprising that congregations and faith-based outreach programs have received the nod to shoulder a greater role in addressing the level of poverty the country endures (Cnann, Sinha, and McGrew, 2004). Of the westernized world, the United States stands as one of the most religious societies with 82% defining themselves as religious (Cnann, Sinha, and McGrew, 2004). With the passage of the charitable choice provision of the 1996 welfare reform legislation, congregations and faith-based outreaches that have long worked in an environment absent the limelight have received a considerable amount of attention. Under the charitable choice provision, further solidified by the establishment of the White House Office of Faith-Based and Community Initiatives in 2001 by President George W. Bush and continued with slight alteration under the current administration of President Barack Obama, the estimated 250,000 to 400,000 congregations within the country enjoy the opportunity to apply for federal funding to assist in their delivery of a variety of social services without compromising their religious beliefs and values (Cnann, Sinha, and McGrew, 2004). With the enormous and infiltrative system of congregations and faith-based outreaches, it is the hope of many that these organizations will be able to utilize their concentrated community presence to effectively meet the needs of those who desperately need not only temporal assistance, but also spiritual therapy and support. President Barack Obama has continued to support and further develop such initiatives during his tenure in office.

The shift to heavier reliance on congregations and faith-based organizations to alleviate poverty has not been void of scrutiny. In a country that is based upon the separation of church and state, civil liberties organizations including the American Civil Liberties Union, the America Jewish Committee, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and the Americans United for Separation of Church and State, have not hesitated to voice their opposition to the faith-based initiatives. With the opportunity for congregations and faith-based organizations to be bolstered by federal funding, civil liberties organizations are concerned that the wall separating church and state will receive a formidable blow, undermining the First Amendment by allowing tax-payer dollars to support the potential proselytizing efforts of congregations and faith-based outreaches that mix religion with their social services (Lewis, 2003). Opponents of congregations and faith-based organizations as government-funded social service providers also voice fears of consumer dependence on scale with past arguments of welfare abuse. This perception has bled into the general public, fueling many sentiments that instead of assisting those in need, food banks and other similar programs instill the idea that people are unable to meet their own needs without outside assistance (Molner, Duffy, Claxton, and Baily, 2001). Beyond the areas of government policy, critics pose questions concerning the overall effectiveness of congregations and faith-based organizations when compared to other non-religious organizations that deliver a variety of social services. Indeed, there is a limited pool of research that examines the efficacy of religiously minded service organizations. It is enticing to attempt to corral the hundreds of thousands of congregations and faith-based organizations into tidy, easily measurable units of systematic service delivery, but one cannot forget that these organizations are extremely diverse in their size, level of religiousity, theological views, and other crucial aspects (Cnann, Sinha, and McGrew, 2004). Furthermore, it should be noted that congregations and faith-based organizations routinely provide services that are challenging to objectively measure for research or economic purposes. How does one quantifiably measure the respect, charity, and genuine friendship that congregations and faith-based organizations pride themselves in integrating with their outreach efforts (Wuthrow, Hackett, and Hsu, 2004)?

It is, in fact, these characteristics that supporters of faith-based initiatives cite as the essential ingredient for success in the fight against poverty. Beyond filling mouths and clothing bodies, many, including former President Bush and current President Obama, uphold the efforts of congregations and faith-based organizations in their effort to transform those that they serve in a way that secular service organizations cannot. Injecting the aspect of faith into the process of social service delivery creates an environment that can cultivate a deep change within an individual and lead to overall greater levels of effectiveness (Lewis, 2003). Volunteers and staff of congregations and faith-based organizations, themselves inspired by their faith and its communal aspect, are naturally inclined to adopt a relational approach to their delivery of social services. This supportive and caring outlook addresses not only the temporal need at hand, but takes on a transformative affect, making the consumer feel connected and in charge of their own lives (Ebaugh, Pipes, Chafetz, and Daniels, 2003; Yancey and Atkinson, 2004).

The utilization of highly motivated volunteers by congregations and faith-based organizations, in cooperation with the emphasis on self-accountability provided by their religious views, has created an effective weapon in the fight against substance abuse and prison recidivism. The flexible and relational based environment that is a token quality of these organizations creates a support net that provides a healing, familial atmosphere. Spiritually oriented “12-step” style programs like Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous have found marked success by adopting a faith-based approach to the formidable problem of substance abuse in the United States. Programs such as these are not only economically thrifty, but can also be more effective than their secular counterparts. In one study, nearly 46 percent of substance-dependant men who participated in a faith-based “12-step” style treatment program remained abstinent one year after discharge, while those who received treatment from a secular agency yielded an abstinence rate of 36%. This level of effectiveness owes in some part a nod of gratitude to staff members, some of whom have overcome addictions and now devote themselves to helping others travel the same tough path. This approach can cultivate a deep sense of hope in men and women who find themselves substance-dependent but able to draw inspiration from those whose experienced and understanding hand reaches out to them. Furthermore, after discharge, this support system can be called upon for strength and encouragement rather than utilizing another secular service agency or counseling service (Humphreys & Moos, 2007). Like the United States, Puerto Rico has long fought a battle with substance abuse and drug addiction, but has found an effective ally in faith-based programs in rehabilitating substance-dependent citizens. After the Puerto Rican legislature defined drug abuse and dependence as a spiritual and social problem, faith-based treatment programs were entrusted with the arduous task of finding and executing a plan of treatment. Of those treatment programs registered with the Puerto Rican government in 1998, 75% were faith-based in nature. Many of these programs are organized and run by former addicts and follow in the paths of Christian treatment services found in the United States, utilizing pastoral counseling, bible study, prayer, and peer support systems as an approach to achieving independence from addiction. Among Hispanics, association with a religious organization had a significant impact on their drug using tendencies (Hansen, 2004). In short, the injection of faith into the arena of inpatient substance abuse treatment programs is an investment, but one that has proven to pay off.

Faith-based organizations and congregations can also serve as another site for the delivery of medical care. DeHaven et al. (2004) found that faith-based health programs can produce positive results by increasing knowledge about disease, leading to improved health screening, and increasing willingness to change lifestyle. They also state that faith-based programs reduce the risk associated with disease and disease symptoms. Since as many as 57% to 78% of congregations offer health related activities, the ground is fertile to expound upon existing programs. Should there be an increase in the collaboration between professional healthcare personnel and faith-based organizations, it is possible that the benefits could be shared at an even greater degree of service.

Congregations and faith-based outreach programs have also extended their caring and relational approach to the field of social services. In creating a community environment similar to those found successful in drug treatments, these programs have capitalized on a familial method to address poverty and temporal need. Many congregations and faith-based outreach programs are able to spontaneously react and adapt to fluctuating needs and circumstances of individuals who seek assistance. The lack of bureaucracy and government protocol is a flavor unique to congregations and faith-based outreaches and enables them to value friendly relational time spent with clients as much as meeting quotas or formal procedures (Cnann, Sinha, and McGrew, 2004). This characteristic is a hallmark of such programs, where many times, downtrodden individuals receive not only the assistance initially sought, but also an invitation to become part of a wider family and community.

Useful products from Amazon

Method

Procedure

Initial intake data was collected from 521 new clients of the Cornerstone Outreach Center of Amarillo, Texas from February 2000 through July of 2000. Follow-up outcome evaluation data were collected approximately 90 days after the first visit to the Cornerstone Program. This time frame offered sufficient time for clients to fully experience the various services provided by the program. Incoming new clients of the CornerstoneOutreachCenter completed a four-page intake instrument prior to receiving services in order to successfully evaluate their needs before acceptance into the program. The four page intake form was self administered and took approximately fifteen minutes to complete. Data were collected on such factors as demographics, socioeconomic status, needs, family (social support), spirituality, and religiosity (religious practices). After completing all required material, clients met with a volunteer counselor further need’s assessment. During this meeting the counselor also spoke with the clients in detail about their spiritual status, specifically asking if they accepted Jesus Christ as their Lord and Savior, and presented a gospel message during each counseling session. Each client was required to attend church sermons prior to receiving services of the CornerstoneOutreachCenter. The sermons, held on Tuesday mornings, lasted between sixty to ninety minutes. Upon conclusion of the worship service, the clients lined up for food and/or clothing distribution. Clients requiring additional services were handled on a case by case basis, including but not limited to, job referrals, job counseling, or assistance with rent or utilities. During each subsequent visit during the following 90 days, clients completed a service utilization form which recorded their name, date, and services received.

The response rate for the follow-up outcome evaluation was 39% with a total of 207 participants completing both the intake interviews as well as the follow-up. Individuals completing both instruments were included in this study. It should be noted that attempts, although unsuccessful, were made to contact all of the programs 521 new members for the follow-up interview. The outcome evaluation interviews were conducted with the aid of the Cornerstone Outreach Center Staff from May of 2000 through October of 2000. The outcome evaluation interviews collected the same information as the initial intake form, including measures of service and program satisfaction. The outcome evaluation interviews also evaluated whether individuals that utilized services offered by the program more frequently experienced a higher degree of satisfaction. The initial attempt for follow-up contact was made by phone. These efforts, however, were largely unsuccessful because many clients were transient, had moved, or had their phones disconnected. Discussions with the director and staff of CornerstoneOutreachCenter led to another unsuccessful attempt involving invitations to attend a free dinner hosted by Cornerstone. Finally, volunteer staff members visited clients’ residences to administer the outcome evaluation interviews. This approach proved to be the most fruitful. Volunteers were paid $20.00 for each survey collected and clients were given $5.00 for their participation.

Instrument Development

A primary consideration in developing the forms to be used in the evaluation process was the length of the instrument itself. The large number of clients participating in the program each week was also a factor. An instrument was developed that would take no more than roughly fifteen minutes for completion. Literacy rates in the surveyed area of this population were estimated to be very low and so the survey was formatted to be at an eighth grade reading level. Some participants, however, still required assistance to complete the required forms.

Participants were assessed using a variety of dimensions including demographics, socioeconomic status, food security, need, social support, spirituality, and religiosity. The topic of food security was assessed on three levels: 1) the number of days the client and/or their children were hungry but did not eat because there was not enough discretionary spending for food, 2) the monetary allowance for food purchases, 3) the amount of money left monthly after living expenses were deducted that would be spent on groceries. The guidelines used were adapted from the USDA Food Security Brief Module. The participants were asked to rate the level of need based on a scale of 1 -5, 1 = no need, and 5 = severe need. The single item indicators of need were related to the principal services offered at the CornerstoneOutreachCenter, including food, clothing, employment, counseling and spiritual support. Other needs assessments were used for exploratory purposes to aid the program staff in service delivery choices.

Participants were asked to rate the quality of their relationships (social support) with family, God and their overall satisfaction with life in general. These measures of social stability were rated on a scale of 1 -5, 1= extremely unsatisfied, while 5 = extremely satisfied. The higher scores indicated higher levels of perceived satisfaction. The Cronbach’s Alpha scale was used to determine the median level of satisfaction. The score was .84, indicating acceptable internal consistencies among the participants. The spirituality and religiosity measures included social indicators adapted from the General Social Survey (GSS; Davis, Smith, & Marsden 1972-2004 ), along with other items developed by our researchers specifically for this study. The majority of the spirituality questions were also rated on a scale of 1-5, 1 = extremely important in the clients every day lives, and 5 = not at all important. This scale was designed to reflect a higher level of spirituality in the clients’ lives. The questions set forth were to probe the importance of religion, faith in God, church involvement, etc., in the clients’ daily lives. Internal consistency was again measured using Cronbach’s scale, and reportedly was very high, at Cronbach’s alpha = .91. The items used for religiosity scale were church attendance, participation in church activities, prayer, etc. The respondents were asked on the following scale 1 - 5, 1 = regularly active, and 5 = an answer of never, this methodology reflected higher scores as a moderate to inactive participation within the clients faith-based organization. The reliability for the religiosity scale was surprisingly high at a Cronbach’s alpha score of .86.

Participants

The sample of 207 new Cornerstone clients was predominantly female (78%), half were White, 30% were Hispanic, and 21% were African American. Thirty-one percent of the participants were married and 30% were single. The median age of respondents was 38 with a median educational level of 11 years. The majority of participants (78%) were unemployed with a median income of $586.50 per month. The proportion of the sample reporting any type of financial aid (TANF, food stamps, HUD, etc.) was very low, fewer than 10% reported receiving any type of government assistance. A wide variety of religious denominations was represented in the sample; 23% are Catholic, 35% Baptist, 26% Protestant, and 15% Other. The Protestant category includes individuals who identified themselves as Christian, Church of Christ, Holiness, Nazarene, Pentecostal, and Assembly of God. The "Other" category includes Lutherans, Methodists, Latter- Day Saints, Jehovah Witness, Non-denominational, and Inter-denominational affiliations. Few participants were unaffiliated (n = 7) and these individuals were excluded from all analyses. The sample was fairly evenly split on current church attendance; 49% currently attended and 51% did not currently attend church. Clients attending the worship service constituted 46% of the sample and 54% were walk-in clients.

Results

Process Evaluation

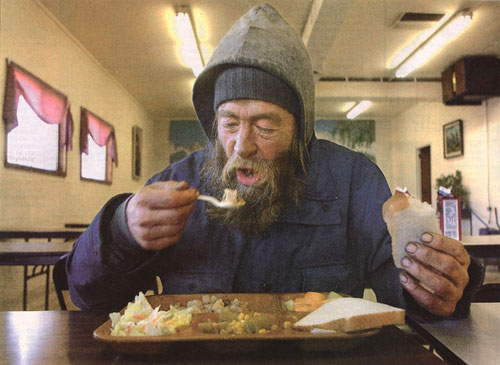

A total of 521 new clients completed an intake form and were tracked to examine the number and the types of services that were utilized during the ninety days following initial admission into the program. It was of interest to first examine the descriptive statistics related to needs of the clients. The primary service provided by the CornerstoneOutreachCenter is food distribution. In that vein, clients were asked the number of days during the past month (30 days) that they were hungry but did not eat because they could not afford it. The mean number of days hungry was 4.1. In addition, clients indicated that they spent an average of $77.25 on food per week which represents 54% of their weekly income. Clients were also asked to rate their needs across 12 dimensions (see Table 1). The three highest ranked needs were food, employment, and clothing, whereas the lowest ranked needs were drug treatment, alcohol treatment, and childcare.

In terms of service utilization, it was found that clients attended CornerstoneOutreachCenter an average of 1.33 times during a 90-day interval. Table 2 shows a more detailed breakdown of the service utilization by the number of visits to the center within a ninety day interval following the first visit. It was found that more than 80% of the clients visited the center only one time. In addition, only 3% of the newly admitted clients visited the center more than three times during the study. This number indicates that very few attendees frequented the center more than a couple times within the three month time period and did not “abuse” the system. The sample was further subdivided on the basis of current church attendance in order to incorporate a characteristic that could potentially be related to service utilization. Cornerstone clients typically receive food, clothing, or counseling after attending worship service. However, many new clients walk in on other days of the week. These walk-in clients do not attend the worship service and so provide a natural, albeit imperfect, comparison group for assessing differences in service utilization among those who received a higher dosage of a spiritual message compared to those who received lesser spiritual influence. Since there is a strong spiritual dimension to the program, it was posited that individuals who are current church attendees might possess be exposed to resources that may result in more service utilization because they may come back for spiritual guidance rather than for material goods. There were no differences when comparing service utilization among individuals who attended church service and those who did not attend church services across all measures (i.e., service utilization, 12 needs).

The study also examined the reasons for client visit(s) to CornerstoneOutreachCenter. Table 3 shows what services were utilized by program participants. Note that the percentages on Table 3 add up to more than 100% because clients could receive multiple services. The majority of clients attended in order to receive food (75%), clothing (31%), and employment assistance (15%) during their initial visit. Only a small percentage of clients attended for counseling, spiritual guidance, or other reasons (4%, 6%, and 5% respectively). Table 3 also shows the reasons why clients visited Cornerstone following intake (subsequent visits). It is of particular interest to note that there were dramatic decreases in clothing (31% vs. 16%), and employment assistance (15% vs. 3%), whereas a marked increase for spiritual guidance (6% vs. 32%).

Outcome Evaluation

The second part of the analysis consisted of examination of pre-post measures across a variety of indices to assess if changes occurred during the course of the program. A total of 207 clients completed both the intake evaluation form and the outcome evaluation form. With regards to hunger, there was a decrease in the number of days hungry (M=5.6, SD = 10.4, vs. M=2.7, SD=4.0) during the past month, t (56) = 2.051, p < .05. There was also a decrease in the need for food (M=4.47, SD=0.92 vs. M=3.40, SD=1.35) t (157) = 8.421, p < .05. Clients reported an increase in overall monthly income (M=643.89, SD=422.50, vs. M=732.15, SD=446.30) during the pre-post examination, t (104) = -2.227, p < .05. Another significant change was an increase in employment rates among the clients, rising from 23% to 35%. Examination of the pre-post findings indicate that clients were more employed, less hungry, and had fewer needs, although social support, spirituality, and religiosity did not change.

Discussion

In times of hardships, faith-based outreaches and congregations are essential in meeting basic human needs, including food and clothing assistance. Programs such as these also provide spiritual nourishment and guidance, an aspect of well-being that is not dealt with in typical welfare programs. At a time in one’s life when it seems as if the world is collapsing and even fulfilling the fundamental necessities of daily life is overwhelming, being able to hope in faith is an encouragement. Faith-based organizations and congregations also provide a variety of services, some of which are not found in state or federal assistance programs. When compared to most state and federal assistance programs, faith-based outreach programs and congregations have fewer restrictions for qualification for assistance. In some cases, these programs are the only answer for the most pressing needs of individuals and families. The CornerstoneOutreachCenter strives to achieve two main goals. The faith-based organization wishes to provide services such as food and clothing assistance, employment assistance, counseling, spiritual guidance, drug and alcohol treatment, medical and dental care, and transportation assistance to the destitute individuals of the Amarillo, Texas area. As a secondary goal, the organization wishes to spread the Christian faith through catechesis and example, thus inviting more individuals into a conversion process and a personal relationship with Jesus Christ. This organization successfully met the first goal of efficiently providing services as clients were more employed, less hungry, and had fewer needs, with particular needs success in regards to food, employment assistance, and clothing assistance. However, the second goal of increasing congregation size and leading clients to conversion was not accomplished. There was no evident change for the program’s participants in the areas of religiosity or spirituality, although an interesting figure that could lead to a promising avenue of future research surfaced in the process evaluation data. Of those returning to CornerstoneOutreachCenter seeking further services, 32% sought spiritual guidance. This is a marked increase from the 6% of clients seeking guidance of this type earlier in the data collection. One possible explanation for this increase could be the fresh introduction of spirituality and religious practices to clients at Cornerstone. Developments in the area of spirituality generally take time to take root and grow. During this time, it is possible that clients may have had further questions regarding aspects of faith and religiosity. The increase in the need for spiritual guidance is held in contrast with the outcome data which indicate no changes in measurements of spirituality and religiosity. One possible explanation for this seeming discrepancy could be the short amount of time that staff at CornerstoneOutreachCenter had with individual clients. Data were collected over a period of three months, during which time the staff at Cornerstone serviced many individuals. It may be that increased, or more routine, contact is necessary for clients to feel comfortable sharing their desires concerning faith and religion. Furthermore, three months may not be a long enough interval for a new interest in faith to solidify into action. Perhaps a measurement period of longer than three months would capture an indication of change in attitudes and behaviors of spirituality and religiosity.

CornerstoneOutreachCenter utilized a unique method in presenting services and faith to their clients. As a consortium of churches working together, Cornerstone provided the opportunity for clients, if they so desired, to freely select among congregations to further their spiritual and religious practices. This multi-denominational approach fostered a supportive environment in which spiritual growth was encouraged, but not forced. This could serve as a possible model for other faith-based organizations and congregations that provide services similar to CornerstoneOutreachCenter. Adopting an approach such as this could decrease the chance that a single denomination would impose their faith on clients seeking services.

A concern of critics of faith-based organizations and congregations is the possibility of further abuse of government funds by habitual use of a facility’s services without effort on the client’s part to increase their own level of independence. With 80% of the clientele seeking assistance from CornerstoneOutreachCenter only one time, it is clear that abuse of faith-based outreaches by habitual repeat visitors did not occur at a significant level. Only 1.6% of clients utilized services on five or more occasions during the 90 day period between the collection of intake data and outtake evaluation.

While garnering valuable data on the social service strengths and weaknesses of a faith-based outreach program, the research performed at the CornerstoneOutreachCenter did encounter some limitations. While the total number of clients utilizing services through the organization at the onset of data collection numbered 521, only 207 clients were able to complete both the intake and follow-up outcome instruments. While multiple efforts were made by both the facility’s staff and the research workers, a total of 314 participants were not able to be included in this study, due to not completing both instruments. This difference was due to external situations beyond control of the CornerstoneOutreachCenter staff and research workers, examples being the clients had moved, or no longer had a phone to be contacted. Perhaps future researchers will be able to overcome this obstacle in order to have a larger sample population size. As indicated previously, another area of possible alteration in future research could involve lengthening the time interval of measurement from three months to a longer period. This may allow data to show greater changes in spirituality and religiosity.

As the United States experiences devolution in traditional welfare programs, faith-based organizations such as the CornerstoneOutreachCenter are valuable tools utilized in an attempt to overcome the persistent gap between fulfilling the needs of the downtrodden with the existing and frequently overburdened state and federal services. Rogers et al. (2005) stated that the result of governmental devolution in the 1990s has increased the need for faith-based organizations and congregations. Programs such as these are receiving growing recognition as a valuable community resource for addressing the social and economic needs of individuals and families, particularly those that are poor, marginalized, or otherwise vulnerable. Beyond meeting needs left unfulfilled by existing programs, faith-based organizations and congregations are of little cost to the state and federal governments. Relying on a predominantly volunteer-based work force fueled into service oriented activity by Gospel values, the services provided by faith-based organizations and congregations could be a promising ally in the battle against the poverty that infiltrates the nation. According to Cnaan (2001), the average yearly monetary value of each faith-based organization and congregation in the Philadelphia, Pennsylvania area is estimated at $117,852.72. With about 2,095 congregations in the region of research, Cnann (2001) calculated that the annual replacement value of the entire system of congregations would reach $246,901,440. This impressive figure shows the immense societal need for programs such as CornerstoneOutreachCenter and how programs like it are providing substantial assistance and perhaps, an increased sense of wellbeing and hope, to the inhabitants of communities across the United States. With continued access to federal funding made possible by the Charitable Choice provision of the 1996 welfare reform and further buoyed by the 2001 establishment of the White House Office of Faith-Based Community Initiatives, it is the hope of many that faith-based organizations and congregations will continue to be a positive influence in the lives of the downtrodden. Organizations like CornerstoneOutreachCenter offer promising potential, as indicated by data, and provide a supportive environment with the capacity to increase the quality of life of clients with little cost to the government. Faith-based organizations and congregations have the ability to see and serve both temporal and spiritual needs in an environment of respect, support, commitment, and hope.

References

Cnaan, R.A., Sinha, J.W., McGrew, C.C. (2004). Congregations as Social Service Providers: Services, Capacity, Culture, and Organizational Behavior. Organizational and Structural Dilemmas. 28(3/4), 47-66.

Lewis, B.M. (2003). Issues and dilemmas in faith-based social service delivery: The case of the salvation army of greater Philadelphia. Administration in Social Work. 27(3), 87-106.

Molnar, J.J., Duffy, P.A., Claxton, L., & Bailey, C. (2001). Private food assistance in a small metropolitan area: Urban resources and rural needs. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, 28(3), 187-209.

Wuthnow, R., Hackett, C., & Yang Hsu, B. (2004). The effectiveness and trustworthiness of faith-based and other service organizations: A study of recipient's perceptions. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 43(1), 1-17.

Ebaugh, H.R., Pipes, P.F., Saltzman Chafetz, J., & Daniels, M. (2003). Where's the religion? Distinguishing faith-based from secular social service agencies. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 42(3), 411-426.

Yancey, G.I., & Atkinson, K.M. (2004). The impact of caring in faith-based social service programs: What participants say. Social Work & Christianity. 31(3), 254-266.

Humphreys, K., & Moos, R.H. (2007). Encouraging posttreatment self-help group involvement to reduce demand for continuing care services: Two-year clinical and utilization outcomes. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research. 31(1), 64-68.

Hansen, H. (2004). Faith-based treatment for addiction in Puerto Rico. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 291(23), 2882-2882.

DeHaven, M.J., Hunter, I.B., Wilder, L., Walton, J.W., & Berry, J. (2004). Health programs in faith-based organization: Are they effective?. American Journal of Public Health. 94(6), 1030-1036.

Rogers, R.K., Yancey, G., & Singletary, J. (2005). Methodological challenges in identifying promising and exemplary practices in urban faith-based social service programs. Social Work & Christianity. 32(3), 189-208.

Cnann, R.A., & Boddie, S.C. (2001). Philadelphia census of congregations and their involvement in social service delivery. Social Service Review. 75(4), 559-580.

Table 1

Ratings of Client Needs at Intake

Need Rating

Food 4.5

Employment 3.1

Clothing 2.9

Dental Care 2.7

Transportation 2.2

Job Training 2.2

Spiritual Guidance 2.2

Medical Care 2.1

Child Care 1.7

Counseling 1.7

Alcohol Treatment 1.1

Drug Treatment 1.1

Note: Need assessments were on a 1-5 Likert-scale anchored as follows: 1=no need….5=severe need.

Table 2

Service Utilization of Cornerstone Clients

Number of Visits Percentage of Clients

1 - 80.6%

2 - 13.8%

3 - 2.7%

4 - 1.3%

5 - 0.8%

6 - 0.0%

7 - 0.2%

8 - 0.2%

9 - 0.0%

10 - 0.0%

11 - 0.0%

12 - 0.4%

Table 3

Type of Service Utilization of Cornerstone Clients at Intake and 90 Days Following Intake

Reason for Visits Percentage of Clients at Intake Percentage of Clients

Following Intake

Food 74.9 89.8

Clothing 30.5 16.1

Employment Assistance 14.6 2.8

Counseling 4.4 0.3

Spiritual Guidance 6.1 31.8**

Other 5.0 1.7

**spirituality scales by denomination concluding there not attending on regular basis