Global Warming Science: A Thumbnail History

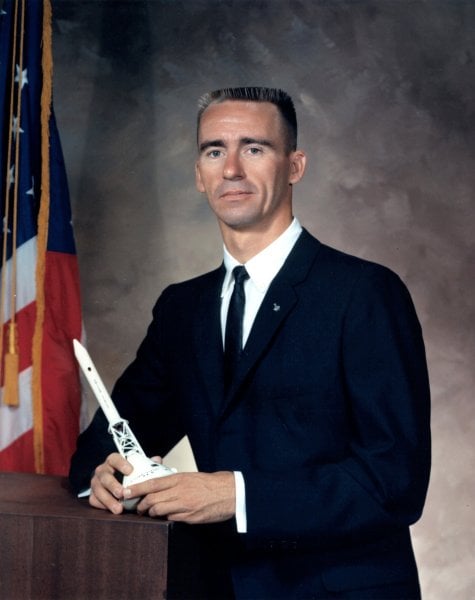

On August 14, 2010, retired astronaut Walter Cunningham wrote:

About 20 years ago, a small group of scientists became concerned that temperatures around the Earth were unreasonably high and a threat to humanity. In their infinite wisdom, they decided:

1) that CO2 (carbon dioxide) levels were abnormally high,

2) that higher levels of CO2 were bad for humanity,

3) that warmer temperatures would be worse for the world, and

4) that we are capable of overriding natural forces to control the Earth’s temperature.

With all due respect to a living American hero, it’s a strange vision when you think about it.

After all, it asks us to believe that “a small group of scientists” could, starting from nothing sometime around 1990, influence most of the national governments of the world to call an expensive conference in order to create the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (May 9, 1992) in order to solve a problem that--supposedly--none of them had ever heard about before.

If true, this vision would surely mark an all-time highwater mark in the political clout of the international science community! Of course, Colonel Cunningham does allow the scientists 'infinite wisdom' to help them in accomplishing this feat of persuasion.

In reality, one can begin the story in Napoleonic France. In 1801 mathematician Joseph Fourier, newly appointed Prefect of Isère, relocated to Grenoble, the “capital of the French Alps.” He became interested in climate, and by 1824 had constructed the first terrestrial “heat budget.” It showed that the atmosphere must act to raise the temperature of the Earth.

Fourier compared this still-mysterious effect to a scientific instrument—one similar to a miniature greenhouse.

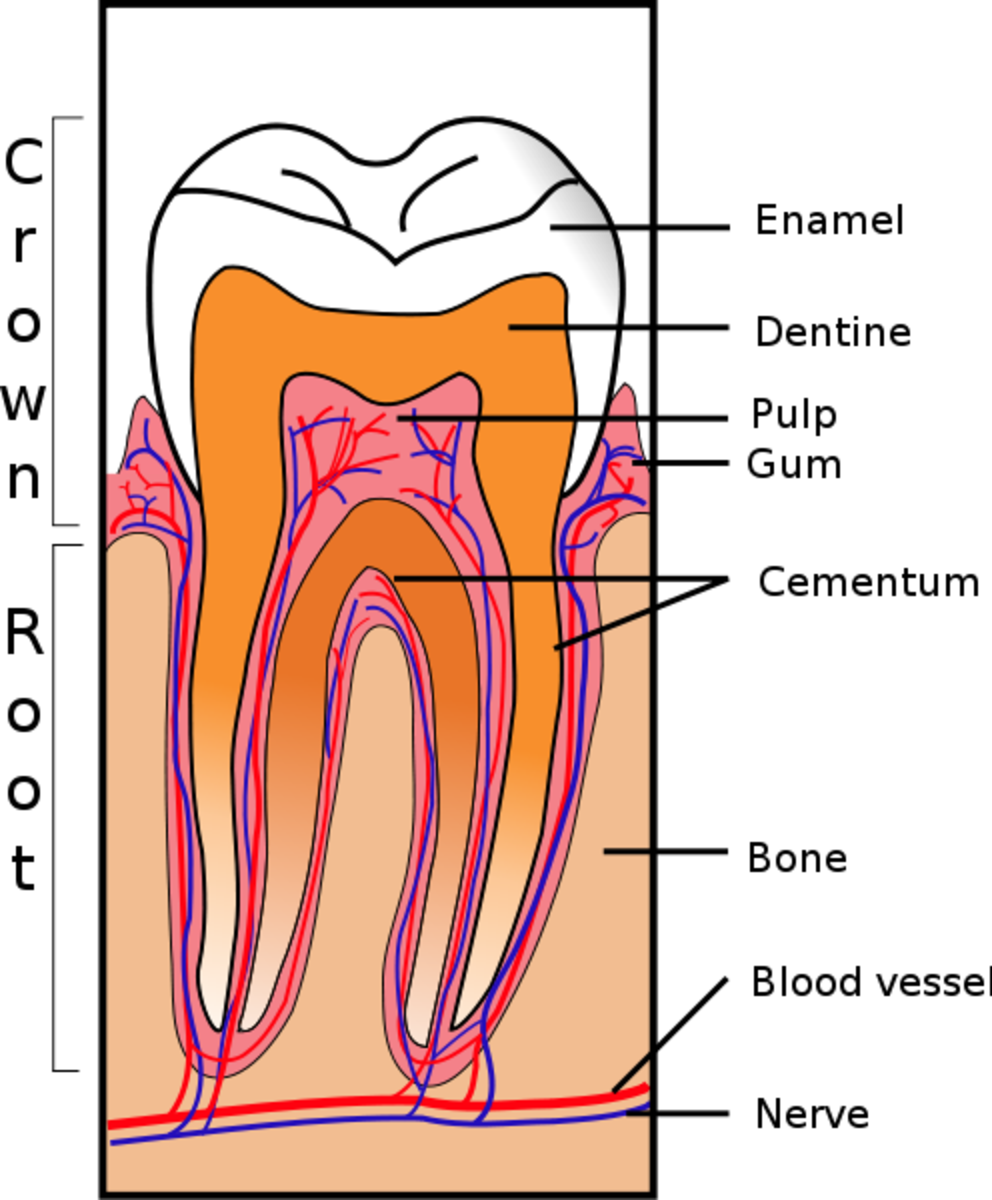

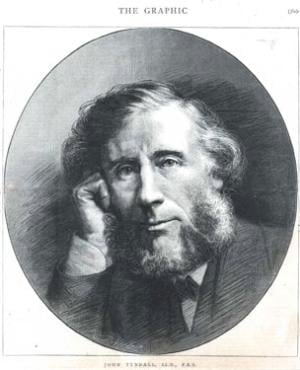

Awareness of the Ice Ages was dawning in Fourier’s time, and by 1859, Anglo-Irish physicist John Tyndall had become interested. He began to study how various atmospheric gases transmit heat, and to his surprise found that some, though transparent to visible light, partially blocked radiated heat. Most notable among these were water vapor and carbon dioxide.

This, then, was the mechanism of Fourier’s “greenhouse effect!”

But causes of the Ice Ages remained controversial, and in 1896 future Nobel prize winner Svante Arrhenius investigated. Using Samuel Langley’s atmospheric infrared radiation measurements, Arrhenius hand-calculated the effect of carbon dioxide on temperature, finding that a drop in concentrations could indeed cause an Ice Age. Unfortunately his insight, mired in technical controversy, soon languished.

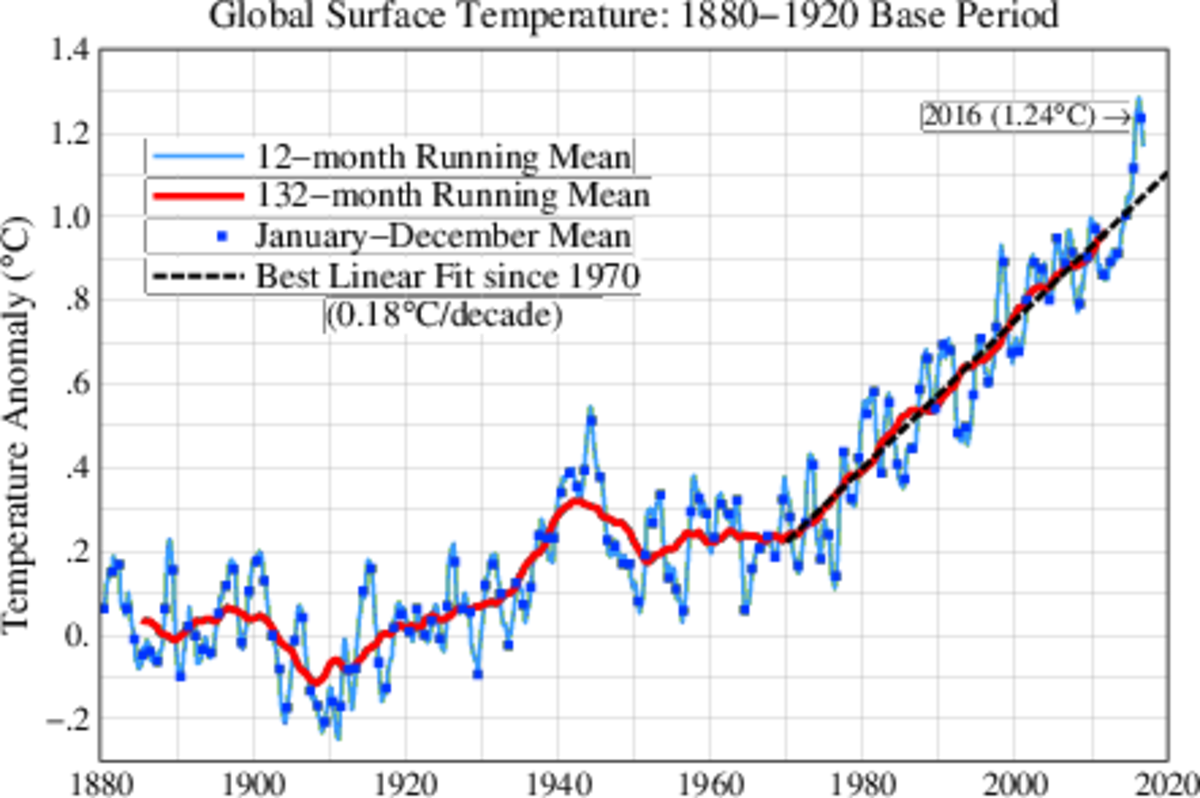

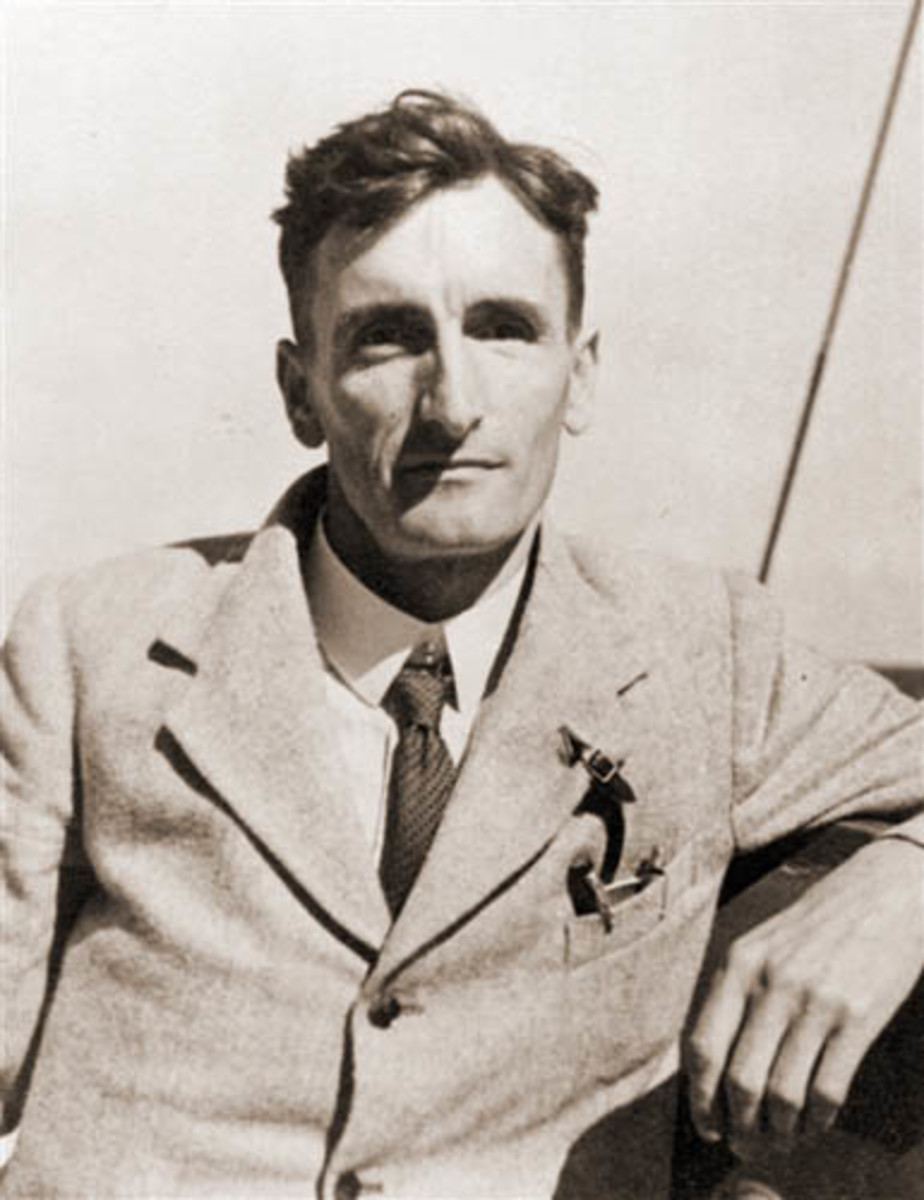

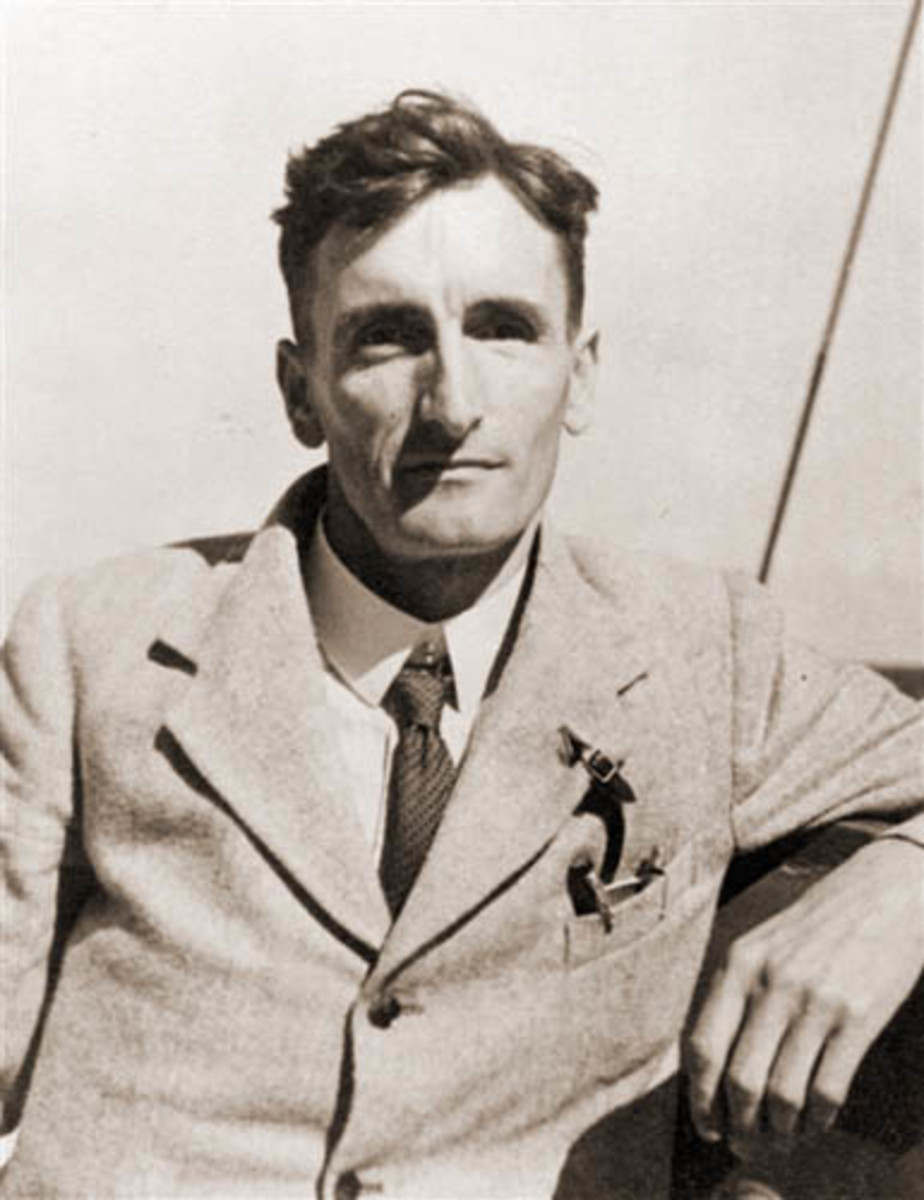

In 1938 British steam technologist Guy Callendar brought carbon dioxide theory back into focus. Using newer, better measurements, he demonstrated anew the carbon dioxide greenhouse effect. He showed that the planet actually was warming, and suggested that fossil fuel consumption was responsible.

During the 1950s several scientists took up Callendar’s results. Charles Keeling began accurately measuring atmospheric carbon dioxide—a program still continuing. Physicist Gilbert Plass, applying a computer to the latest heat radiation data, first calculated a complete description of the radiative process between ground and space. Swedish scientists Bolin and Erikson showed that the oceans couldn’t absorb carbon dioxide fast enough to compensate for human emissions.

Slowly, awareness of global warming’s potential “dark side” arose. Arrhenius and Callendar had welcomed the prospect of warming. But the International Geophysical Year (1957-58) underlined the linkage of all Earth’s systems, and widened scientific perspectives—the warming so attractive to the Swedish Arrhenius seemed quite a bit less so to Indian or African scientists.

The first alarms were sounded in the US. Congress had heard in 1957 that warming could bring an ice-free Arctic and create “real deserts” in America. But during the 70s concern deepened; a 1970 MIT study warned of “widespread droughts” and “changes of the ocean level,” a 1974 CIA report foresaw the world’s food supply at risk, and in 1977 the National Academy of Sciences envisioned a whole suite of consequences as “adverse, perhaps even catastrophic.” Concern spread globally, and international conferences assessed human health impacts (1979) and called on all governments to develop climate change policies (1985).

It is this long story of science and growing awareness, sketched so very briefly here, that produced the 1992 Framework Convention--not, as Colonel Cunningham thought, “decisions” by a “small group of scientists.” The saga spans two centuries and thousands of researchers--much more than this brief article can more than begin to suggest.

But that saga should be essential common knowledge, as humanity tries to assess the reality of global warming and its probable consequences. It's an urgent task: should the worst case materialize, climate change could pose an existential test of our collective realism, imagination and intelligence--and most crucially of all, our wisdom.

Related links

- The Discovery of Global Warming - A History

Physicist Spencer Weart tells the history of research on climate change from the 19th century to the present, in a set of hyperlinked essays. The best single resource, bar none, to understanding the history of the science of global warming. - Climate Wars: A Review

The worst consequences of global warming may not be the most obvious. A historian and journalist takes a look. "Gwynne Dyer was not like other war correspondents, back in the day: with other reporters, if there was shooting in the provinces..." - Global Warming Science And The Dawn Of Flight

The "life, work and times" of Svante Arrhenius, who in 1896 hand-calculated the first mathematical model of CO2-induced global warming. "In the middle years of the 1890s, the world was trembling on the brink of breakthroughs and breakdowns..." - Global Warming Science In The Age Of Queen Victoria

The "life, work and times" of John Tyndall, who first identified CO2 and water vapor as primary greenhouse gases. "Perhaps its the dramatic weather changes, or perhaps it is mere coincidence, but mountains recur in the scientists' lives. . ." - The Science Of Global Warming In The Age Of Napoleon

The "life, work and times of Joseph Fourier, who first deduced the existence of the greenhouse effect. "If we think of Revolutionary and Napoleonic France, many things might come to mind: "Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity"..." - Through A Glass Darkly: Equinox Reflections, 2010

A more personal take on climate change--and what it's like to watch it happen. "Its just past the fall equinox, that day when the year turns from light to dark, summer to winter. Days have been growing shorter since the summer solstice..."