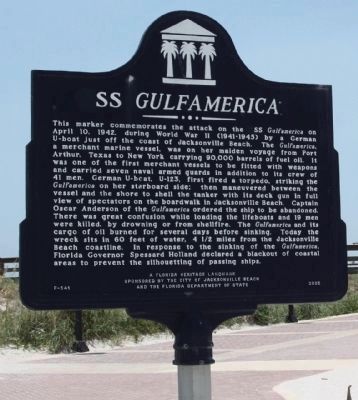

Gulfamerica: WWII, U-boat Victim

Marker at Jacksonville Beach

Gulfamerica Attacked

One of the most significant yet least publicized, military campaigns of early World War-II was ‘Operation Paukenschlag (Drumbeat)’. Designed to disrupt the shipment of war materials and supplies to Great Britain, a small fleet of German U-boats terrorized allied shipping along the east coast of North America and the sea lanes to the United Kingdom.

Their success and the bolder U-boat attacks in the Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico, resulted in the sinking of over 400 ships carrying more than three million tons of war materials sunk during the first six months of 1942. Losses which far exceeded those at Pearl Harbor.

No place served to better display the U-boat’s prowess, and the horrors of war, better than the evening seventy years ago when the Jacksonville Beach skyline exploded into a gigantic ball of fire as the tanker Gulfamerica, carrying 100,000 barrels of oil, took a direct torpedo hit from a German U-boat less than five miles off shore. The flames, visible from St. Marys, Georgia to south of St. Augustine beach, drew several hundred spectators from crowded weekend nightspots along the beach.

The events of the next 12 hours brought World War II much closer to Jacksonville than the evening newspaper but, the attack was not reported by the local media although several hundred people watched the explosion and the ensuing gunfire,.

According to Dr. Michael Sweeney, Author of “Secrets of Victory,” the Office of Censorship’s rationale was that the Germans knew they had torpedoed the ship, but might not have known whether it had been sunk. “Announcing that fact might have given valuable information to the Germans,” Sweeney said. “. . . the sinking might not have made news even though people standing on the shore of northern Florida could have watched the freighter burn.”

Korvettenkapitän Richard Hardegen

Maiden Voyage

The Gulfamerica was on her maiden voyage out of Port Arthur, Texas bound for New York. Traveling unescorted about 5 miles off Jacksonville Beach, she was silhouetted

by the lights of the beach, where no blackout was in effect. Just after 10 p.m. the tanker stopped steaming the standard evasive zigzag course and took a northerly course.

About 75 minutes earlier the German U-boat U-123, under the command of Kapitänleutnant Reinhard Hardegen on his second patrol hunting and destroying maritime traffic along the eastern seaboard, spotted the Gulfamerica. The target was well north of U-123 as Hardegen started pursuit.

According to author Michael Gannon’s best-selling book, Operation Drumbeat, Hardegen was elated. “It’s huge, heavily loaded. . .” he called to his first officer, “and fast -- maybe 12 knots. It’s hugging the coast. We’ll have to turn screws to catch it.” Hardegen ordered a 340-degree course at top speed hoping to position U-123 for a broadside shot.

Concerned that the glow of the marine phosphorescence in their wake might be visible to the tanker or any passing aircraft Hardegen decided to slow the boat and attempt a firing from behind the target. He realized this was a more difficult shot since the ships would be traveling at different speeds.

As the boat closed to within just over a mile of the Gulfamerica, Hardegen gave the command: “Permission to fire at 2000.” Seconds later Hardegen could feel the movement of the boat as he heard, ‘Rohr eins – los’ Tube one – fire.

The calm seas and phosphorescence made it easy for Hardegen to watch the torpedo as it started its one-hundred and seventy-five second journey to the Gulfamerica. It was 10:22 pm, and the music from the bars and nightclubs was soon to be drowned out.

Aerial Photo of Gulfamerica Mortally Wounded

The Sinking

The torpedo struck the tanker on the starboard side, triggering an explosion and ball of fire to rise into the dark sky as burning oil spilled into the sea. The Gulfamerica’s Captain knew immediately the damage was fatal and ordered the engine stopped and the ship abandoned while the radio operator issued distress calls.

Only Hardegen wasn't finished. He wanted to ensure that the Gulfamerica would sink. He ordered his crews to man their guns as he cautiously approached the burning hulk. The flames were so bright he could see the spectators lined up on the beach and the boardwalk which ran along the shore. Concerned that his weapons might well overshoot the ship and injure civilians, he maneuvered U-123 around the stern and positioned the boat between the shore and the tanker.

The maneuver was risky, U-123 was now silhouetted by shore lights and the boat was in much shallower water which would make avoiding detection more difficult if it was forced to dive. About a dozen shells from the deck gun were fired into the engine room. In minutes, the stern of the tanker was stern aground.

Hardegen decided this was sufficient and the boat left the area headed south remaining on the surface for speed. Later in his logs, the U-boat commander wrote “All of the vacationers have seen an impressive special performance at Roosevelt’s expense. A burning tanker, artillery fire, the silhouette of a U-boat – how often have all these been seen in America.”

As the U-boat pulled away, the chaotic evacuation of the tanker continued. The ship carried a crew of 48 including seven naval guards who were to man the 4-inch aft gun and the two forward 50-caliber guns. None of the tanker’s guns fired on the U-boat that night.

With the stern on the bottom and burning oil in the water, launching the lifeboats was difficult. One capsized dumping its occupants back into the fiery Atlantic. Another moved away from the tanker quickly with the Captain and ten crewmen aboard. Several others abandoned ship on a life raft and plucked other crew members from the water.

Several small civilian vessels and fishing boats came out to help the Coast Guard patrol boats rescue the survivors who were taken to Mayport. At final count, five men died from the torpedo blast and gunfire from the U-boat while another 14 drowned after jumping overboard.

The previous day, the USS Dalhgren, under the command of LCDR Robert William Cavenage, departed pier Baker at the Naval Operations Base in Key West. The ship, a 23-year-old destroyer, had been assigned to Key West for less than a month. It was to serve the Fleet Sonar School and carry out patrol missions. The destroyer took a northerly heading up the coastline, zig-zaging and alternating speed and heading according to standard avoidance plans.

In the late afternoon of the 10th, the ship received orders from the Navy’s Gulf Sea Frontier in Key West to proceed to St. Augustine and initiate sweeps for U-boats from St. Augustine to Fernandina. The Dalhgren arrived in the area around midnight and began sweeping the area.

At 2:15 a.m. a PBY-3, one of the highly successful Navy long range reconnaissance and air-sea rescue aircraft from NAS Jacksonville flew low over the Dalhgren and dropped flares. Within minutes another plane dropped more flares and the destroyer went to general quarters. With no instructions from Key West, the flares were assumed to indicate a U-boat in the area.

U-123 quickly ran into ran into problems leaving the tanker area. Three Navy PBY-3s were flying patterns over the area dropping magnesium illumination flares. From their base at Jacksonville Municipal Airport, the Army’s 106th Observation Squadron dispatched several B25 Mitchell bombers to aid in the search for U-123.

Another ship in the area, the Asterion, had spotted a U-boat and had reported by radio the time and location of the sighting. Both the Dalhgren and U-123 intercepted the report. Hardegen was sure it was U-123.

In minutes an aircraft dropped parachute flares behind the boat and Hardegen saw a second plane sending Morse code signals. The Dahlgren came into view on the starboard side and began to answer with a long coded response. With the flares still burning, Hardegen saw yet another plane, without lights, diving at the boat when he ordered a crash dive.

Hardegen wrote in his diary account for that night, “We never had such a crash dive. When I fell through the hatch the plane was almost on top of us.” At 20 meters, the boat hit bottom and began a slow track towards deeper water for protection from the feared Wabo’s (short for wasserbomben, German for depth charge).

U-123 German U-Boat

The Escape

The fact that U-123 had been sighted made it easier for the Dalhgren as it passed directly overhead. Six depth charges were dropped and Hardegen’s boat took a beating. According to Hardegen’s diary, ‘. . . crew members fly about, and practically everything breaks down. Machinery hisses and roars everywhere. We break out the escape apparatus.’

The Dalhgren had U-123 on the ropes. The port engine was down. Critical valves were damaged and bubbles were rising to the surface identifying the boat’s position better than any radar system. Hardegen could hear the sounds of the destroyer returning.

As the Dahlgren passed overhead the crew braced for the attack. Hardegen had already decided if they survived this Wabo attack, he would give the command to abandon ship. But the sounds of the destroyer propellers increased and then died away with no sounds of the deadly Wabo’s.

The crew continued assessing the damage from the destroyer’s single attack. The engine room reported that most of the batteries were damaged and there was a ‘hellish’ noise from bent propeller shafts. The destroyer made two more passes over the crippled U-boat without releasing Wabos. Then the sounds of the destroyer began to fade.

The escape gear was stowed and the crew set to work on repairs to the battery system and the hydroplanes that would be required to surface. Hardegen realized that if they could surface they would still be the prey, but there were no options. Less than two hours following the destroyer’s attack, U-123 broke the surface to the light of a crescent moon and no sight of their hunters.

The Dahlgren made no request for naval or airborne assistance and at 4 a.m. she stepped down from general quarters and moved off to the Northeast, away from U-123.

Two days later, in its battle-weary condition, U-123 used its last torpedo to sink the 2,609-ton freighter Leslie off Cape Canaveral. Two hours later Hardegen used his deck guns to sink the 2,647 ton Swedish freighter Korsholm in the same area.

Hardegen gave the orders to head for the Gulf Stream and home. With limited ammunition remaining for his deck guns, Hardegen could not pass up one last easy target. On the 17th, he sank the American 4,834 ton Alcoa Guide 300 miles east of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, his final target. U-123, Hardegen and crew reached their home port at Lorient, France on May 2, 1942. It was his last combat patrol

On April 16th, the Gulfamerica whose stern rested on the bottom with a 40-degree starboard list finally rolled over and slowly disappeared to its watery grave.

Harry F. Sinclair - Tanker

A Deadly Week

The week following the attack on the Gulfamerica was costly to the U.S.merchant fleet. Eight freighters/tankers were attacked and destroyed in the seven day period

April 11th

Gulfamerica - The tanker was torpedoed and damaged in the Atlantic Ocean 5 nautical miles (9.3 km) off Jacksonville, Florida by U-123 with the loss of nineteen of her 48 crew. Survivors were rescued by United States Coast Guard patrol boats. The hulk sank on 16 April.

Harry F. Sinclair, Jr. - The tanker was torpedoed and damaged in the Atlantic Ocean 7 nautical miles (13 km) off Cape Lookout, North Carolina by U-203 with the loss of ten of her 36 crew. Survivors abandoned ship and were rescued by the Royal Navy's HMT Hertfordshire. The burnt-out ship was later towed to Morehead City, North Carolina. She was subsequently repaired and returned to service as Annibal in 1943.

12 April

Delvalle - The cargo ship was torpedoed and sunk in the Atlantic Ocean by U-154 with the loss of two of ther 63 people on board. Survivors were rescued by the Royal Canadian Navy's HMCS Prince Henry or reached land in their lifeboats.

Esso Boston - The tanker was torpedoed and sunk in the Atlantic Ocean 300 nautical miles north east of Saint Martin by U-130. All 37 crew were rescued by USS Biddle and the USS PT-35

13 April

Leslie - The cargo ship was torpedoed and sunk in the Atlantic Ocean off Cape Canaveral by U-123 with the loss of four of her 32 crew. One survivor was rescued by Esso Bayonne, the rest reached land in their lifeboats. Leslie was raised and scrapped in August 1954.

14 April

Margaret - The cargo ship was torpedoed and sunk in the Atlantic Ocean off Cape Cod, Massachusetts by U-571 with the loss of all 29 crew.

16 April

Robin Hood - The cargo ship was torpedoed and sunk in the Atlantic Ocean 200 nautical miles southeast of Nantucket Island, Massachusetts by U-575 with the loss of fourteen of her 38 crew. Survivors were rescued by the USS Greer.

17 April

Alcoa Guide - The cargo ship was shelled and sunk in the Atlantic Ocean 300 nautical miles (560 km) south east of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina by U-123 with the loss of six of her 34 crew. Survivors were rescued by USS Broome and the UK's Hororata.

Epilogue

Scuba divers who visit the wreck site today report that there is only a ghost-like mass of plates, pipes and debris, to remind us of Jacksonville’s introduction to the realities of the war and the first and final voyage of the Gulfamerica.

Dan Hughes, a Scuba diver and member of the Jacksonville Reef Research Team who has been down to the wreckage several times remembers, "... a sense of reverence that I felt when we began our descent." Hughes said, "It seemed like a memorial for the merchant mariners who lost their lives on this ship." Commenting on the fact that very little of the wreckage was identifiable to those exploring the wreckage, he noted, "I was quickly overwhelmed by how mother nature has healed the scars of war by softening the jagged edges of steel with corals and sponges. I found myself surrounded by life, vivid and colorful. I ascended to the surface with a sense of peace and solace."

Hardegen, was, one of the top German submarine aces, He sank over 25 ships while a U-boat commander. In 1990 Jacksonville welcomed him back as a respected guest, for his humanitarian actions in risking his life to avoid killing spectators on the beaches that April night.

Reinhard Hardegen brought U-boat warfare to the doorstep of New York Harbor and Jacksonville Beach in the winter of 1942. He died died 76 years laler on June 9, 2018 He was 105.

Operation Drumbeat

Submarines at War: A History of Undersea Warfare Hardcover

U-Boat War

Knights of the Wehrmacht: Knight's Cross Holders of the U-Boat Service