Why Are All Ugly People Evil?

The Fall of the Rebel Angels

Behold the above painting!Pieter Bruegel the Elder represents the Biblical fall of the rebel angels with a binary physiognomy. The mythological tale is that some angels rebelled against God--either out of envy or drive for greater power--and were cast down to Hell by God's loyal forces. The theological analysis is that the fallen angels were given the ultimate freedom of choosing God or not-God, good or evil. In the painting we see the evil angels clearly marked out by their grotesque shapes, the deformity of their bodies. They are ugly, even hideous. One imagines the uglier, the more evil they be. The good angels, Michael in his golden armour and fellow angels in flowing light robes, are the epitome of Renaissance beauty. They are fair-skinned with long hair, their bodies thin and delicate, their faces handsome and androgynous. It is not that the fallen angels were ugly from the get-go, but that their falling twisted their 'bodies' into vile forms. A physiognomy follows from the relationship between beauty and moral state: the capacity to judge the moral state from the appearance.

Richard III

But I, that am not shaped for sportive tricks

Nor made to court an amorous looking-glass;

I, that am rudely stamped, and want love's majesty

To strut before a wanton ambling nymph;

I, that am curtailed of this fair proportion,

Cheated of feature by dissembling nature,

Deformed, unfinished, sent before my time

Into this breathing world scarce half made up,

And that so lamely and unfashionable

That dogs bark at me as I halt by them -

Why I, in this weak piping time of peace,

Have no delight to pass away the time,

Unless to spy my shadow in the sun

And descant on mine own deformity.

And therefore, since I cannot prove a lover

To entertain these fair well-spoken days,

I am determined to prove a villain...

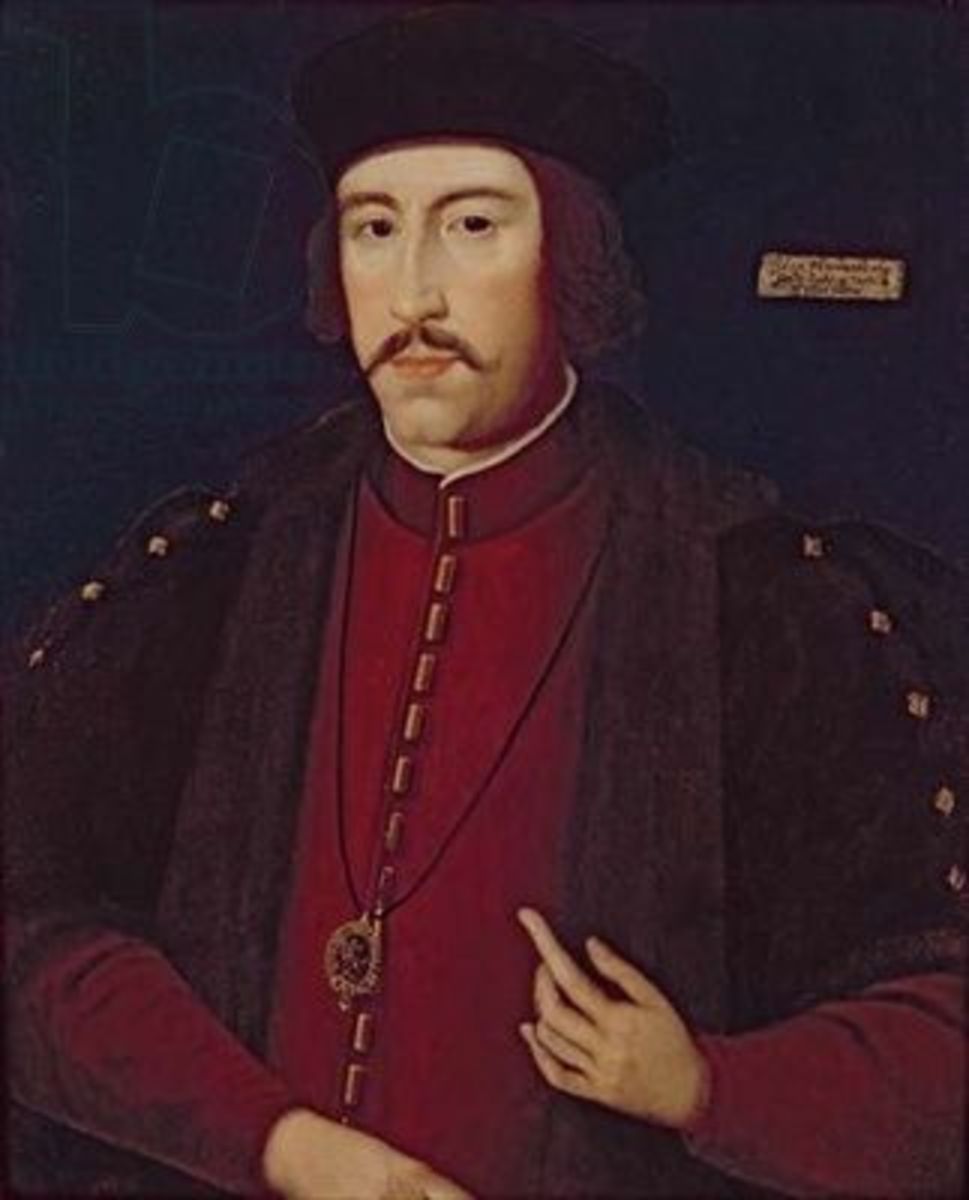

In Richard III, Shakespeare conforms to the false view of Richard III concocted by Holinshed and other historians that Richard was deformed, a hunchback. Shakespeare has Richard go through his ugliness like a litany. Performances of Richard III have emphasized this trait, with Antony Sher adopting long, black, two-pronged sticks with which to scuttle about the stage like an insect--reminding one of the famous opening lines of Kafka's Metamorphosis, "Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from uneasy dreams to find he had been turned into a gigantic insect." As Kafka's insect is despised by characters within the story, the mere appearance of Richard III in Sher's performance is intended to repulse the audience. His appearance is enough to decide he is somehow unwholesome, dangerous.

In fact Richard III's deformity was an invention of political opposition to his reign. Shakespeare used the notion for dramatic reasons. One of which is apparently a causal link between being ugly and being evil, "And therefore, since I cannot prove a lover...I am determined to prove a villain..." Although Richard's soliloquy is hardly reliable, Shakespeare has him draw a link between his own inability to find love as an ugly man and his decision to be a villain. Richard III's villainy, of course, involves his taking the throne by scheming and murdering; one wonders if sexual frustration is sufficient, if the relationship between his ugliness and his evil is more metaphysical. On the other hand, Richard twice attempts a seduction in the course of the play, succeeding once, suggesting that perhaps Richard's frustrations are sexual and that there is a relationship between the drive to power, the drive to sex and beauty.

Medusa

The relationship between good and evil in Richard III is not unlike the relationship between salvation and action in Protestant theology. To Catholics, and as imagined by non-Christians, the Christian prepares him/her self for salvation through good works based in faith. In Protestant theology, however, one is already either saved or not saved; good actions are merely the result of being determined as saved, a symbol by which one can tell who is saved. Similarly, Richard III's doesn't cause him to be evil, it is rather a symbolic representation of his evil nature. This notion develops from Plato onward. Plato introduced the concept of an internal disorder: the appetites, anger and reason can lose their delicate balance. The Judeo-Christian philosophers adopted Plato's thought and applied to it their characteristic analogical mode of thought, whereby the four seasons correspond to the four elements, the four personality types, the four substances of the body, and so forth. Analogically, a disordered soul and a disordered body become linked in the poetic imagination.

This, however, is once the full Christianization of Europe has been more or less achieved. The Greek myths, predating Plato, show a different vision, but no less potent one. Medusa, the beautiful Gorgon who, albeit vain, is hardly evil, is raped in the Temple of Athena. Athena is offended and issues a punishment to the Gorgon: she is to be so incredibly ugly that she turns to stone all who look upon her. In Medusa, the ugliness itself is the evil: they are truly one, and not symbolic one of the other. The evil is thus entirely on the surface and by no means morally implicates Medusa. Quite the opposite, Medusa appears to be a true victim. It is only with Italian peplum films that Medusa become a vicious monster desirous of turning warriors to stone.

What is of significance about Medusa, however, is that her ugliness is taken the be sufficient justification for her death. The hero Perseus is sent to take her head, which he dutifully does with some help from none other than Athena. Perseus is represented in traditional fashion as a hero slaying the monster. Never is Perseus represented as a villain or at least misguided character sent to perform an immoral task. Although it is true Medusa has turned some into stone, the problem can be ended simply by avoiding Medusa. The evil is an accidental and not an essential condition; it rests on the surface, like color. However, there is a refusal to separate Medusa from the harm caused by her ugliness. There is no remorse for Medusa because she is ugly. She is represented as a monster deserving of slaying; and she is so represented because she is so very ugly.

The Devil Effect

So we find throughout history that the attitude toward ugliness as evil has not vanished but only mutated and taken on subtler forms. Ugliness was once taken to be evil itself, a form of evil afflicting the one who has it like a disease. The ugly one was a victim or host of the evil. Come the Renaissance, the ugliness itself was no longer evil, but a symbolic manifestation of internal, hidden evil. The attitude has still not vanished today, but has mutated still to fit the times.

In 1972 a study was conducted by Dion, Berscheid & Walster on the relationship between perception of beauty and judgments on character. Photos were given to participants who were asked to rate the attractiveness of those in the photo and to rate the personality traits of the person based on the photo. It was found that those consistently rated attractive were also taken to have the most desirable personality traits. In 1975 a study by Zanna & Peck found that women are inclined to alter their opinions to fit those of an attractive man, but do not alter their opinions for unattractive men. The study concluded that the women unconsciously associated attractiveness with intelligence and wisdom, even superior to their own. What is at play in both of these studies is a conjunction of a beautiful-is-good stereotype and a cognitive bias called the "halo effect," in which the good of one trait is conceptually extended to other traits. The trait of beauty, being stereotyped as representing good, spreads out over the other traits of the beautiful person. The opposite of the halo effect is, naturally, the devil effect, in which the one negative trait, ugliness in this case, is extended over other traits.

Returning to the actual devils, in The Fall of the Rebel Angels one sees the ugly forms representing the evil interior of the fallen angels. With the devil effect, however, this attitude mutates into a yet subtler form. Now the relationship between ugliness and evil is situated within the realm of social interaction as a heuristic cognitive bias. It is not that the ugly person contains a disordered soul or that the evil ugliness has been thrust upon him or her, but rather the ugliness of the person, a very immediate trait, becomes the dominant trait from which the whole person is judged as 'evil'. The evil is a product of imputing rather than an actual property or at least a property acquired via the expectation of the imputing. Nevertheless, the effect is the same and just as real; this is the same attitude in a new guise.

Beauty, Sex and Power

The beauty one sees in another person is not the same as the beauty of a sunset or the beauty of an artwork. One appreciates the sunset and the artwork in a peaceful mode, free of anxiety. The appreciation of human beauty is anxiety-ridden and coupled with primal desire, an organic impulse towards possession: one wants to cuddle the beautiful child, to captivate the beautiful potential mate, to resist desiring the non-potential mate. The beautiful thus have an erotic power, like the beautiful good angels dominating the ugly fallen angels in The Fall of the Rebel Angels.

Richard III's response to the domination of the beautiful is to strive for absolute power with a modus operandi he terms 'villainy'. Coming increasingly closer to power, he attempts seduction. His response to a lack of power to possess the beautiful is to substitute for beauty political power and to use political power the obtain the objects of erotic desire. The ugly are moved to strive for power as substitute for erotic power and striving for power is often a movement against others, whereas beauty is always effortless and for others. Yet, though beauty is for others, it is held over others and masters; similarly, though striving is against others, it can be opened before others and serve. There is nothing inherently evil in power, but only in the methods by which a Richard III pursues it. This method is a perversity and not a necessity.

The beautiful angels in their androgynous glory Narcissus-like gaze upon their own good selves and desire nothing else, while the rebel angels are cast into the abyss in twisted forms against their will. But the evil was their will. Cast into this world in forms not nearly as plastic as we wish, our wills have nearly infinite plasticity and it is the will that is the locus of evil. And Medusa against her will is made both ugly and evil in one fell punishment, god-deprived of the will to anything else. If perhaps the eye of Pieter Bruegel were shared by the masses, the twisted forms might be revealed in the disharmony of the will and not the will surmised from the flesh.

And yet, we look forward not to salvation, but the next mutation of the bias.