Personal Responsibility: A Moderate Perspective

Bruce Springsteen singing an old Woody Guthrie song

The Basic Issue

Many of the controversial questions of our time come down to the issue of individual responsibility. Do people fail or succeed primarily as a result of their own personal efforts, or are we mostly victims (or benefactors) of circumstance? In other words, does success in life come from hard work and skill or from the blessing of good fortune? To demonstrate the significance of these simple questions, I will show how the issue of personal responsibility is central to our views on the general topics that I seem to write about the most: politics, religion, and education.

Politics

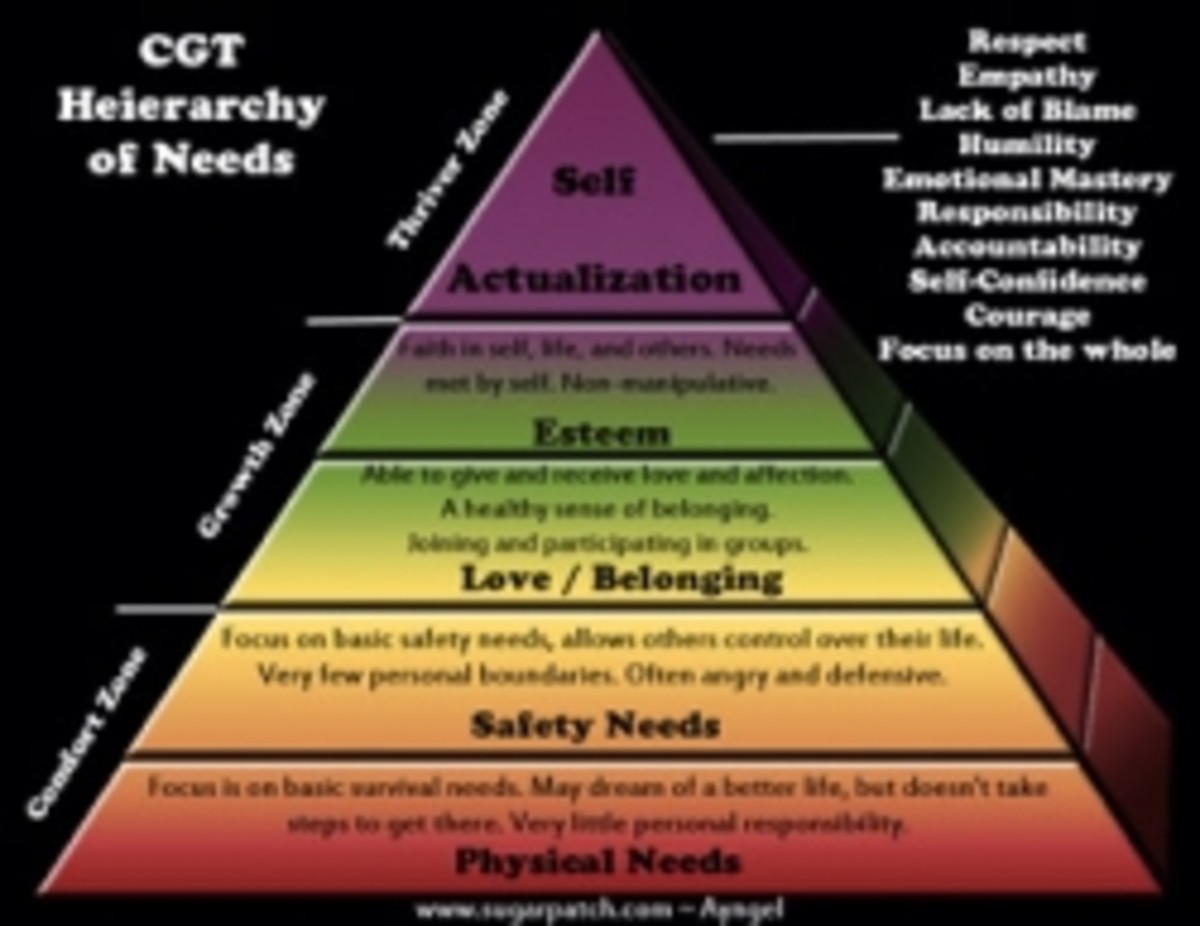

If you see or hear about people who are suffering from poverty or homelessness, what is your initial reaction? Some might wonder what a homeless man did to put himself into that situation. Others might feel sympathy for this person who is clearly the victim of an unjust world. You could learn a lot about a person’s political ideology from his or her answer to this simple question. Conservatives would tend to see the person as a screw up. Few, however, would argue that all homeless people, regardless of circumstances, should be left to rot on the streets. They generally support the idea of charity, but they tend to think that private charitable organizations do a better job of helping the poor than government. Still, only the hard-core Libertarians argue that all government social services should be eradicated. Liberals, on the other hand, would be more likely to see the person as a victim. In their minds, government is obligated to help the homeless fulfill their basic human rights, and steps must be taken to deal with the systemic problems that create homelessness in the first place. Few, however, would argue that government should give lavish benefits to all poor people, even those who are perennially lazy. Individuals, after all, must have some incentive to be productive citizens.

Religion

Most major religions teach that people will be rewarded or punished in some way in a life that continues after death. This may be the ultimate example of personal responsibility. The problem, however, with religions such as Islam and Christianity, belief systems that put people into clear-cut categories of either saved or damned, is that they do not account for individual circumstances. Some people are born into loving Christian or Muslim homes in which they are conditioned to believe in “the truth” from birth. Meanwhile, others are born into “non-believing” environments in which they may be programmed to believe in other faiths. Others may also face circumstances in childhood that make it difficult for them to grow up as individuals capable of making wise or healthy decisions: parental abuse, mental illness, or traumatic experiences caused by political or economic strife. And still others might die without ever hearing about Muhammad or Jesus. Since it is not an equal playing field, are all people judged by the same simplistic criteria? Extreme fundamentalists might say yes. I suspect that most Muslims and Christians, however, are open to the possibility that God may take circumstances into account when an individual’s judgment day arrives. Personally, I find it hard to believe that an afterlife, if it even exists, consists of only two extreme possibilities: an eternity of absolute bliss or complete misery. The limited alternatives of either heaven or hell do not take into account the complexities of our crazy world and the variety of people who live in it.

Education

When a student fails a class, whose fault is it? Some, including many teachers, tend to assume that it is the student’s fault. If the individual had just worked harder, he or she would have done better. Every semester, I see large numbers of students who clearly put little time or effort into my classes. In many cases, I can’t figure out why they ever took the class in the first place. I do recognize, however, that there may be a myriad of factors that cause students to fail: learning disabilities, problems in their personal lives, physical or mental health problems, growing up in a tough neighborhood with poor schools, and many other factors that led them to attend my class ill prepared to succeed. So what is a community college teacher to do? Do I find out what is going on with every student in my class and adjust the grading standards to suit each situation? Clearly, this is impractical, and some would say it is unfair. A passing grade in a college course, after all, must mean something. In my view, the emphasis must be put on individual responsibility at the college level. If a student faces an issue that is making a class difficult, then that person must go to the teacher and let him or her know what is happening. Then, if that teacher has any sense of compassion or professional responsibility, some degree of accommodation can be made. This does not mean, however, that any one gets a free ride. The tricky part for the teacher is figuring out how to adjust to a student’s specific situation while maintaining high academic standards. As a teacher who has been “out in the trenches” for many years, I can assure you that this is very difficult, particularly when you have classes that sometimes have more than 100 students. Fair or unfair, students must adapt to the teaching style and standards of the professor. It is impossible, after all, for a professor to meet each student’s individual needs. And at some point, young people must come to terms with a world that is not going to bend over backwards to help them.

So Let's Be Practical

People who still allow themselves to think deeply about these complicated issues realize that it is neither practical nor desirable to drift too far toward extremes. We all know that our circumstances result partly from our own efforts and partly from luck. Too often, however, discussions about controversial issues get bogged down with rhetoric and abstractions. Conservatives might dream of an ideal world in which all people are rewarded (or punished) for their individual efforts. Liberals might dream of a world in which no one is a victim of injustice and all people have their basic needs met. Since we do not live in an ideal world, there is little point in spending too much time arguing about which side has the superior ideals. When you get down to the tough work of developing teaching techniques, formulating political policies, and putting your faith in theological concepts that address the world as it is, you realize that extreme positions are not satisfying. You can’t simply blame individuals for every mistake and misfortune, and you cannot turn everyone into a victim. Instead, you must recognize that we live in a messy, complex world filled with individuals who, at different times in their lives, have been screw-ups, winners, victims, and lucky bastards. So if every thinking person is some form of a moderate, then why do discussions about politics, religion, and education often degenerate into shouting matches in which people mock and even demonize those that drift toward the other end of the spectrum? I suspect that this is because it is easier to stick with rhetoric and abstractions. Dealing with practical details, after all, takes so much time and effort, and there are never any simple answers.