Popular Response to Communism in Post-War Eastern Europe

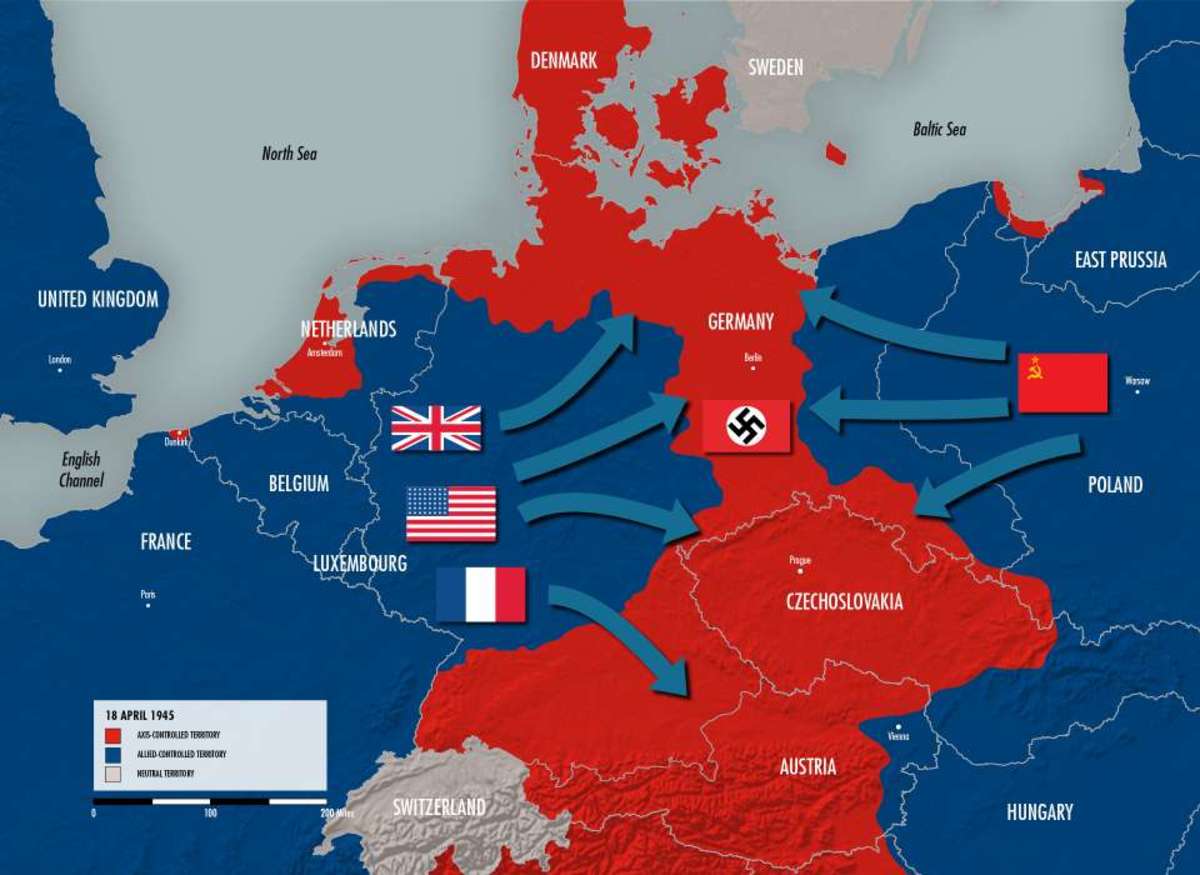

The communist takeover in post-war Eastern Europe was a slow and gradual process. During the late 1940s and early1950s, the communist Soviet Union and the socialist satellite nations merged together to create totalitarian police states all over Eastern Europe to prevent the extremists and the rightist political identities, such as Nazism and Fascism to take control. However, the communists and their radical political ideas divided the Eastern Europeans sharply. Communism attracted some people because they had no confidence in democracy and free market capitalism which led to poverty and economic depression early on. Plus, to some, communism seemed as a viable alternative to the oppression of the World War II and the devastation it caused until 1945. Overall, it was a perfect breeding ground for communism in Eastern Europe in the post-war years. On the other hand, another group of people resented communism and its repressive economic and social policies, and they resisted against it firmly. This is because they strongly believed in the nationalistic ideals of achieving national independence, and living in a democratic nation with complete economic and social freedom. Besides, Stalinism’s gradual failure in Eastern Europe, depicted by the popular uprisings of the 1950s, led people to resist against communism altogether.

Most of the Eastern Europeans resisted the communist takeover of their countries because they strongly believed in nationalism, and wanted to live in a democratic and independent state with social and economic freedom. To achieve their goal, the people in East Germany and Hungary, especially, demonstrated fierce protests against the communist-led governments. They rejected the radical and unfair economic policies, such as an increase of workers’ production with pay-cut and decreased consumer goods production. In East Germany, the Uprising of 1953 was the first major popular resistance against the communists since Joseph Stalin’s death some months earlier. The East Germans fiercely protested against the increased workers’ production levels, which meant they had to work more hours with a severe pay-cut. In addition, the East German government sharply increased food prices while it severely repressed the consumer goods production. As a result, the economy tumbled into a backward spiral, and the protestors went on strike in the towns and cities all over East Germany (“East Germany, 17 June 1953” 2012, 202). Day by day, the uprising grew in huge proportions as the workers and the civilians began to demand for political social reforms, such as holding free and fair elections in a unified Germany, releasing political prisoners, and ending communism completely (“East Germany, 17 June 1953” 2012, 202).

Most importantly, the uprising in East Germany really shook up the faiths of the Stalinist governments all over Eastern Europe. It exposed the limits and the failures of Stalinism, and raised a red flag for the communist leaders who feared a complete loss of authority over the people, if another of those protests occurred in future (“East Germany, 17 June 1953” 2012, 203). In broader terms, the East Germans joined together in a nationalistic effort of bringing about serious political and economic reforms and national independence, from the oppressions of communism (“East Germany, 17 June 1953” 2012, 203). This is well-supported by historical accounts, as Hans Lutzendorf, a journalist in Halle who took part in the protests, says: “A euphoric mood had taken hold of everybody….Most thought of unity, justice and freedom as they were singing, even if they did not have the text in their memory. It was an intoxication that had gripped the crowd, in which complete strangers embraced, women cried and Party comrades furtively disposed of their badges. The demands that were transmitted to the crowd over a commandeered car with a loud speaker mounted on the roof to roaring applause: “Dissolve the government,” “free elections,” “reduction of production quotas,” “lower prices in the state-H0 stores,” and most importantly—“Free all political prisoners” (“East Germany, 17 June 1953” 2012, 205).”

In Hungary, college students and civilians rose up against communism and fiercely pressed for political reforms within the Hungarian government. During the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, the students at the Budapest Technical University resisted against Soviet interference in Hungary and pressured the Stalinist government for several political reforms such as withdrawing the Soviet troops from the country, in order to topple communism altogether. In response, the Soviets launched Stalinist violence to suppress the revolution and the people (“Hungary, 1956” 2012, 167). They murdered several thousands of Hungarians while wounding several thousands more, and imprisoned and executed the Hungarian reformist leaders. The Hungarians fiercely criticized the Stalinist violence and resisted against it, in order to end communism and to bring about fundamental political change in Hungary (“Hungary, 1956” 2012, 167-168). In their nationalistic view, as Laszlo Beke described, “It was murder. Murder, that is, not just of human beings, but of the Hungarian nation (Beke 2012, 168).” In this way, the Soviet-led communist governments’ repressive economic and political policies, and Stalinism’s failure over time, eventually led the Eastern Europeans to resist against communism out of their fundamental nationalistic beliefs.

In another step, communism gained significant amount of traction among people who believed that capitalism was a failure as it only benefited the rich and repressed the poor. According to the author, Glennys Young, during the capitalistic era, the capitalists or the “bourgeoisie” unfairly exploited the workers’ (or the “proletariat”) labor to reap the rewards of capitalism. They seemed to have all the production resources such as machinery, capital, and factories to make profits in expense of the proletariat’s misery (Young 2012, 1). Simply, the rich dominated the poor both economically and politically through the failed capitalistic ideals. Consequently, the proletariat group turned to communism in order to improve their economic conditions. For others like Jacek Kuroń, communism had the potential to destroy the “old order” of the oppressive Holocaust experience, and the exploitation of the Jewish people of Poland during World War II (Kuroń 2012, 35). In doing so, communism could create a “new order” which would promise social justice for every country in Eastern Europe, especially for Poland (“Jacek Kuroń (1934-2004) on the Appeal of Communism after World War II” 2012, 32-33).

Also, the political leaders of Eastern Europe such as Poland’s Jakub Berman consistently justified the effectiveness of Soviet-led communism and its policies. In turn, the popular attraction to communism was also justified. According to Berman, while speaking in an interview in 1980, the Polish communists liberated the country from German occupation and established a more “sovereign” and “independent” Polish state, even under visible Soviet occupation of Poland after World War II (Berman 1996, 44). He really believed that communism helped to save Poland from future military threats from other European countries, especially Germany. Without the communist protection, Poland would have been reduced to a “Duchy of Warsaw” because Germany would have become militarily potent, and would have used force to regain all the territories Poland acquired as reparation for World War II (Berman 1996, 46-47). So, Poland had no other alternatives, other than to adopt communism eventually. Seemingly, nationalism motivated the Eastern Europeans to accept communism earlier, as well.

Finally, we can say that, the argument of resistance to communism overwhelmingly outweighs the argument of attraction to communism. Although communism attracted a group of Eastern Europeans as a promising alternative to capitalism, or a way of establishing a “new order” with social justice in Eastern Europe, it was never a positive solution for economic and political progress. Rather, its repressive Stalinist economic policies of crippling workers’ production level with pay-cuts, along with suppressed living conditions and decreased consumer goods production, devastated the Eastern European economy. Also, communist aggression and Stalinist purges of political leaders and civilians all over Eastern Europe greatly threatened the existence of democracies with political and economic freedom. Consequently, we see that fierce resistance and revolutionary uprisings begin to take place all over Eastern Europe in the early 1950s. The Eastern Europeans, fed up with the repressive economic and political policies, protested against communism out of their nationalistic ideals of living in a democracy with economic and political freedom. These nationalistic uprisings really exposed the Stalinist policies and their failures, and helped to bring about significant political and economic reforms in Eastern Europe, especially in Poland. In truth, nationalism laid out the foundation for ousting communism completely, and building democratic nation-states in a unified Europe later.

Works Cited

Beke, Laszlo. “Hungary, 1956: A University Student Reacts to the USSR’s Violent Suppression of the Hungarian Revolution,” in The Communist Experience in the Twentieth Century: A Global History through Sources, Glennys Young. (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2012), 167-172.

Berman, Jakub. “The Case for Stalinism,” in From Stalinism to Pluralism: A Documentary

History of Eastern Europe Since 1945, Gale Stokes. (Oxford: Oxford University Press 1996), 44-50.

“Chapter 1: Becoming a Communist,” in The Communist Experience in the Twentieth Century: A Global History through Sources, Glennys Young. (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2012), 1-3.

“East Germany, 17 June 1953: Workers (and Others!) Against the “Workers’ State,’” in The Communist Experience in the Twentieth Century: A Global History through Sources, Glennys Young. (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2012), 202-207.

“Jacek Kuroń (1934-2004) on the Appeal of Communism after World War II,” in The Communist Experience in the Twentieth Century: A Global History through Sources, Glennys Young. (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2012), 32-35.

This content is accurate and true to the best of the author’s knowledge and is not meant to substitute for formal and individualized advice from a qualified professional.

© 2020 Zunaid Kabir