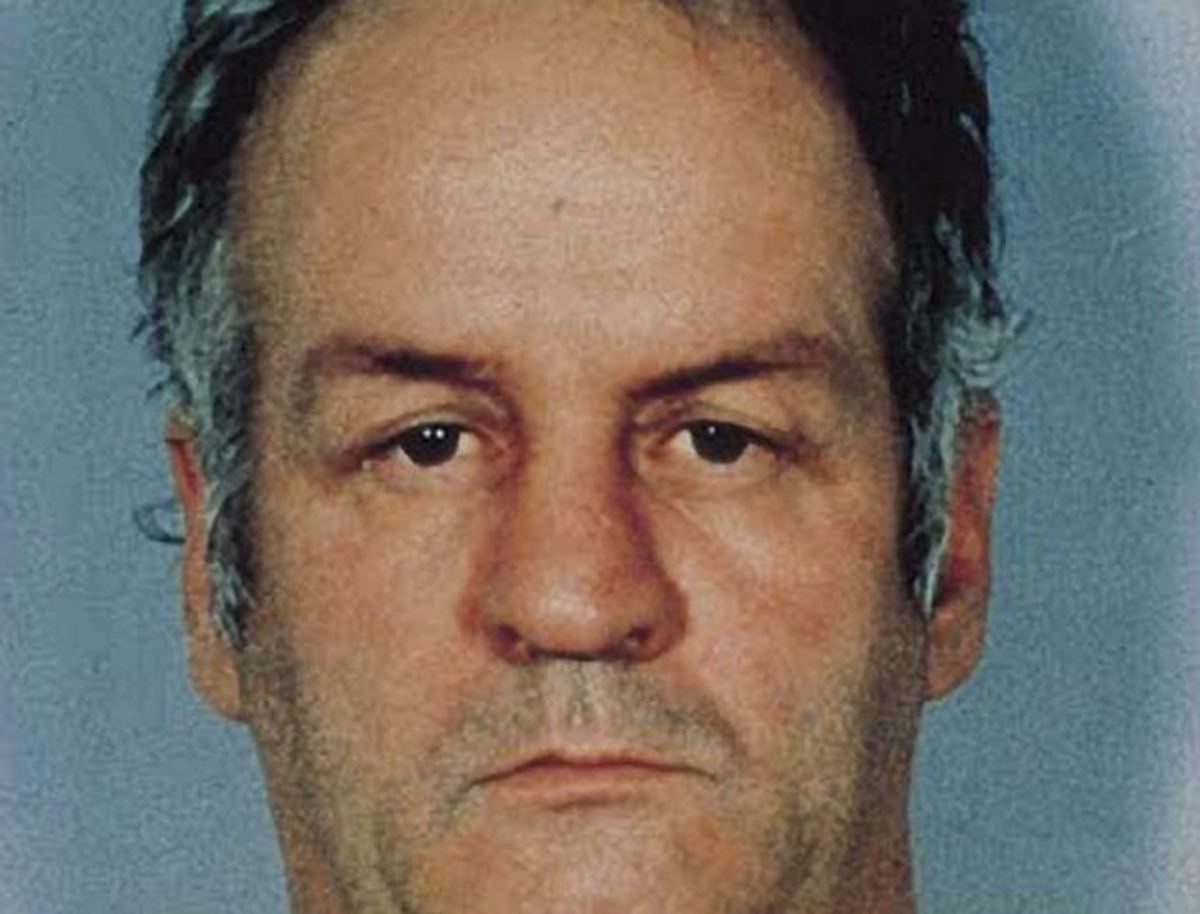

Robert Pickton: How Canada's Most Prolific Serial Killer Got Away With It for Over a Decade

I was gonna do one more, make it an even 50. That's why I was sloppy, I wanted one more. Make... make the big five-O.

— Robert Pickton

The Pickton farm, “Piggy’s Palace,” was a renowned destination for parties and raves featuring Vancouver prostitutes. Robert Pickton claims to have murdered forty-nine women on it over the course of at least eleven years.

The Pickton case sparked public outcry over the apparent failures of the Vancouver Police Department (VPD) and Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) to pursue the myriad tips, missing persons reports, and red flags presented to them by concerned friends and relatives for over a decade.

Pickton Brags About His Crimes

The Case of the Disappearing Sex Workers

The first annual women’s day memorial march organized to press for police investigation into the mass disappearances of women from Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside took place on February 14th, 1991. Even following various increases in numbers of missing women throughout the 1990s, police stated in 1998 that they did not believe a serial killer to be responsible. Until DNA from two missing sex workers was found on the Pickton farm in 2002, the sentiment widely held by police to whom friends and relatives of the victims issued missing persons reports was that the women were drug addicts and therefore were likely on vacation, or having a good time off the grid.

This assumption cost countless women their lives.

Police inquiries years after Pickton’s prosecution state that he began killing in 1991, and that by 1995 — seven years before Pickton was under any serious scrutiny by authorities with regard to the missing women — he was a “fully functioning serial killer”.

The Beginning of a Decade of Apathy

Arguably the most glaring of the red flags overlooked by authorities was Pickton’s attempted murder of a sex worker in 1997; her stab wounds were so extensive as to have her die twice in hospital, and her claim — that Pickton handcuffed her and stabbed her, intending to kill her — was corroborated by the keys to her cuffs present in the clothing Pickton was wearing. Police now believe that by this time Pickton had already killed at least five women, but as his 1997 victim was a heavy drug user, she was declared an unreliable witness and the case against him was stayed in 1998. There were no additional follow-up interviews with the victim.

Witness Det. Const. Lori Shenher of the Missing Women Inquiry into the Pickton investigation testified much later that there was “nothing in [her] interactions with [the victim] that would make [her] question her credibility at all.”

The VPD refused to accept the possibility of a serial killer in the city, dismissing even evidence from their own officers. This denial of severity and connection meant the entire investigation was handed to a single officer, who had no homicide experience or support from her bosses; the RCMP in Port Coquitlam allowed their investigation to lay dormant for months at a time.

When Mounties finally attempted to speak with Pickton in late 1999, they granted his brother Dave Pickton’s request to wait until the “rainy season” when he would be less busy, in the face of dropped murder charges not two years prior. His eventual interview was poorly handled, by officers with no prior interrogation training.

They received a tip that Pickton had a freezer full of human flesh on his farm; even after obtaining his consent to a search, none was conducted.

Even in 2001 the Mounties and VPD’s RCMP-led missing women task force operated under the belief that women were no longer disappearing. That the authorities handling the case were not on high alert, especially in the context of the 1997 attack, is a bewilderment for which they have profusely apologized today.

An Accidental Discovery

It was not until the Port Coquitlam RCMP searched Pickton’s property for firearms, in 2002, and stumbled upon personal items belonging to some of the missing women, that his property was sealed off and investigated for clues.

On February 22nd, 2002, Robert Pickton was first charged with two counts of first-degree murder; four months later, police brought in archaeologists and heavy equipment with which to conduct a 21-month excavation at the farm. This sparked a series of horrifying and gruesome discoveries. British Columbia’s health officer stated that he could not rule out the possibility of human remains having been present in Pickton’s commercial meat. By 2005, Pickton was charged with the first-degree murder of 27 women, and in 2007 he was sentenced to life inprisonment with no chance of parole for 25 years.

The media ban was lifted, and the gory details of the evidence found on “Piggy’s Palace” was made public: skulls stuffed with hands and feet, human remains, jawbones, human teeth, and a .22 calibre revolver with an attached dildo containing both his and a victim’s DNA.

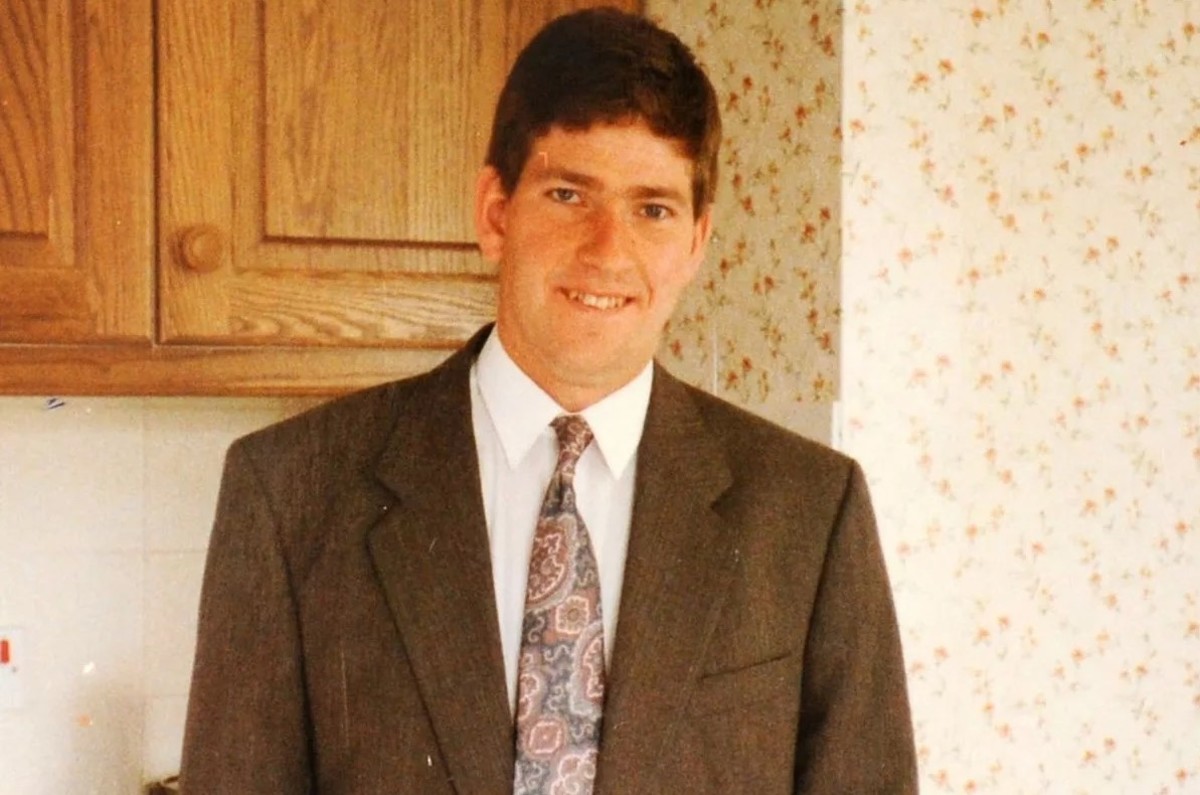

The unpursued 1999 tip turned out quite accurate: his freezer was found to contain the partial human remains of Andrea Joesbury, pictured to the right.

Backlash

Outcry over the handling of the case followed as "Robert Pickton" quickly became a household name, but it was not until Commissioner Wally Oppal’s inquiry and 1,448-page report in 2012 that the police were officially slammed for their failures. “The pattern of predatory violence was clear and should have been met with a swift and severe response by accountable and professional institutions, but it was not,” Oppal said, citing institutional, systemic bias. "The investigations of missing and murdered women were characterized by blatant police failures, and by public indifference.”

The indifference was palpable in all that had to do with the Pickton case, making it all too clear why he chose his victims as he did. Drug addicted and impoverished, and not taken seriously by virtue of their sex work, over a decade’s worth of missing women were effectively ignored. “I have found that the missing and murdered women were forsaken twice: once by society at large and again by the police.” said Oppal, who pleaded for the public to empathize with the victims.

When I talk about systemic bias, I had to ask myself one question: Would the reaction of the police and the public [have] been any different if the missing women had come from Vancouver’s west side? The answer is obvious.

— Commissioner Wally OppalKey Recommendations From the 2012 Public Inquiry

- Enhanced transit: province should implement an enhanced public transit system to allow for safer travel between Northern communities, particularly along Highway 16, the "Highway of Tears"

- Crown Vulnerable Woman Assault policy: province should develop policy to provide guidance on prosecution of crimes involving violence against vulnerable women such as sex trade workers

- Regional policing: provincial government should create Greater Vancouver police force

- Support services: province should provide extra money to allow centres providing emergency services for women in the sex trade to remain open 24 hours a day

- Missing persons website: province should create a site which would educate the public about the missing persons process

- Compensation fund: provincial government should establish fund for children of the victims and for their families' healing

- Equality audits: police forces should be audited with the aim of protecting marginalized women from violence

- Appoint advisors: including one aboriginal elder, to advise with regard to public acknowledgement and apology for mistakes made by the VPD and RCMP

- Law reform funding: provincial government should fund research projects to aid vulnerable witnesses in the court process

City Implementations

Following the release of the 2012 public inquiry report, officials warned that reforms "weren't going to happen overnight." Years later, the families of the victims are growing frustrated with the delays.

“My grandson was eight months old when his mother was murdered,” said Michelle Pineault, the mother of one of the missing women whose DNA was found on the Pickton farm. “He is now a senior in high school. This is not overnight for us; this is a generation. This is a fight that we’ve been fighting for 17 years.”

B.C. Minister of Justice and Attorney General Suzanne Anton spoke in 2014 of the positive changes made to missing persons procedures and policing, but many remain unsatisfied; no progress has been shown towards compensation funds, nor have there been talks of transport reform along Highway 16, nicknamed the "Highway of Tears" after at least 18 female hitchhikers went missing or were murdered along it. Many living along this highway are poor Aboriginals who are often forced to hitchhike in lieu of affordable transit along the 724-kilometre stretch. Members of communities near or along the Highway of Tears estimate that the actual number of missing women is far higher than that reported.

What Can We Do?

It is important that we learn from the tragedy of the Pickton case and the plethora of failures involved, for the Pickton trial was not unique; it was a rehashing of a very prevalent sentiment which to this day inhibits the ability of sex workers and drug addicts to fully utilize legal resources.

The victims were failed by an apathetic police force, but also by an apathetic public.

Addressing public apathy means taking on the personal responsibility of asking ourselves uncomfortable questions about the human tendency to feel disconnected from those whose experiences differ drastically from our own. If the victims had been taken seriously from the early beginnings of the missing persons reports, by either the police or by a more passionate public, Pickton may well have been caught a decade prior; why do we tend to regard sex workers and drug users with less empathy? Why did it take accidentally stumbling upon evidence to finally prosecute Canada's most prolific serial killer?

If any one of the victims had been an educated woman from a wealthy family, would the numerous missing persons reports and tips from concerned relatives and friends have taken a decade to receive any sort of follow up?

How do you think we can cultivate widespread empathy for the weak and vulnerable?