Scientists Can't Make Up Their Minds: Understanding the Scientific Method

The headlines in newspapers, magazines and on the Internet declared that listening to Mozart will make babies smarter. Many parents bought Mozart CDs and faithfully played them everyday. Pregnant women played classical music for their fetuses. Books like The Mozart Effect for Children: Awakening Your Child's Mind, Health, and Creativity with Music were published. The Baby Einstein DVDs were a result of the Mozart craze. Governor Zell Miller of Georgia proposed providing classical music CDs to every child born in the state. All of this was based on a scientific study, which found that listening to Mozart increased IQ. Later studies proved that the Mozart Effect wasn’t real.

It can be very frustrating. One day, a certain vitamin will reduce the risk of developing a certain type of cancer. The next, not only does it not decrease cancer risk, but too much may have negative side affects. It is easy to conclude that scientists can’t agree on anything and that science really can’t be trusted. Scientists just can’t make up their minds.

But what many laypeople see as a weakness in science is actually its greatest strength. Science is constantly filtering out bad or incorrect information. When new evidence comes along that proves old ideas to be wrong, those incorrect ideas are discarded. The problem is that most people don’t know about the scientific method and how it works. The mainstream media usually does a terrible job when it comes to science reporting.

The Problem with Science Reporting

The Mozart Effect craze came about as a result of one study that didn’t even involve babies. The study actually involved 36 college students. The researchers gave the students a pretest; then divided them into three groups. One group listened to Mozart, another group spent 10 minutes in silence and the last listened to a relaxation tape. Afterwards, the students were given a test to measure spatial IQ.1 The Mozart group had a 9 point increase in spatial IQ that lasted approximately 10 to 15 minutes. The results were published in the October 14, 1993 edition of the journal Nature. Most follow-up studies were unable to replicate the Mozart Effect.

Ben Goldacre on science in the media

The real problem here was not the scientists. They were simply doing what scientists do: forming and testing a hypothesis, and publishing the results. The problem was with the science reporting done by the mainstream news. A study that found a temporary increase in spatial IQ in college students was overblown. The media exaggerated the meaning of the study. Commercial interests pushed the idea that listening to Mozart would increase the overall IQ of even babies and the unborn.

Science is so broad, with so many disciplines and sub-disciplines, no science reporter can have an in-depth knowledge of all of them. News editors are drawn to sensational stories and headlines that catch people’s attention. Ben Goldacre, author of Bad Science: Quacks, Hacks, and Big Pharma Flacks said this about science reporting:

"Science stories usually fall into three families: wacky stories, scare stories and “breakthrough” stories."

Examples he gives of wacky stories are infidelity is genetic or chocolate is good for you. The later discredited study by Andrew Wakefield that found a connection between the MMR vaccine and autism is an example of a scare story.

"At the other end of the spectrum, scare stories are – of course – a stalwart of media science. Based on minimal evidence and expanded with poor understanding of its significance, they help perform the most crucial function for the media, which is selling you, the reader, to their advertisers…(Wakefield’s) paper always was and still remains a perfectly good small case series report, but it was systematically misrepresented as being more than that, by media that are incapable of interpreting and reporting scientific data." 2

The Problem with Scientists

Scientists are often criticized for having poor communications skills. It's said that they don’t know how to explain their work to the general public. There is so much jargon in science that many scientists may have a difficult time writing or explaining their work in everyday language. Or they may not want to.

Popular science writers are often scorned by fellow scientists. Popular science refers to scientific topics written for general audiences. Science writer Deborah Blum, author of The Poisoner’s Handbook: Murder and the Birth of Forensic Medicine in Jazz Age New York, said the following about her scientist father:

"…he learned the essential lesson that “real” scientists shared their work only with each other and did not attempt to become “popularizers” because that would lead to “dumbing down” the research."

She went on to say:

"Science writers, journalists, broadcasters and bloggers became the voice of science during a time during which too many scientists simply refused to engage. Scientists have ceded that position of power amazingly readily; ask yourselves how many research associations offer awards to journalists for communicating about science but none to their own members for doing the same. Ask yourself how the culture of science responds even today to researchers who become popular authors or bloggers, public figures. Whether young scientists are rewarding [sic] for spending time on public communication? And ask yourself how hypocritical this is, to complain that the general public doesn’t understand science while refusing to participate in changing that problem?" 3

The TV show The Big Bang Theory humorously addressed this topic. The characters Sheldon and Amy, who are both scientists in the show, attend a presentation by real-life popular science writer Brian Greene, author of The Hidden Reality: Parallel Universes and the Deep Laws of the Cosmos. They sit in the back and make fun of the author. When Greene explains that his book does not assume any math or physics knowledge, Sheldon turns to Amy and says “Hysterical! Wait ‘til you hear how he dumbs down Werner Heisenberg for the crowd. You may actually believe you’re in a comedy club” Sheldon then stands up to ask the author a question. “You’ve dedicated your life’s work to educating the general populace about complex scientific ideas. Have you ever considered trying to do something useful?”4

Problems with the General Public

The general public should take some of the blame too. Science has a huge impact on our everyday lives, literally from when we shower in the morning to when we turn off the light at night. We enjoy the benefits of science all through our day. Science and technology made America the economic and military power it is today. Yet most Americans are ignorant, sometimes proudly so, of many basic concepts in science.

According to Robert M. Hazen and James Trefil, authors of Science Matters: Achieving Scientific Literacy:

"Scholars who make it their business to study such things estimate that fewer than 7 percent of American adults can be classed as scientifically literate."

Our educational system is partly responsible for this high level of ignorance. Even our best schools don't teach math and science very well. According to the 2009 Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), American students ranked 24th in science and 30th in math, despite being 3rd in education spending.

In a film called A Private Universe, Harvard graduates at their commencement ceremony were asked why it is hotter in summer than in winter. Only two out of 23 students answered the question correctly. Many students incorrectly thought it is hotter in summer because the Earth is closer to the sun. You would think at the very least that Harvard graduates would know that it is winter in the Southern Hemisphere when it is summer in the Northern Hemisphere and therefore recognize that this explanation could not possibly be right.

The Scientific Method

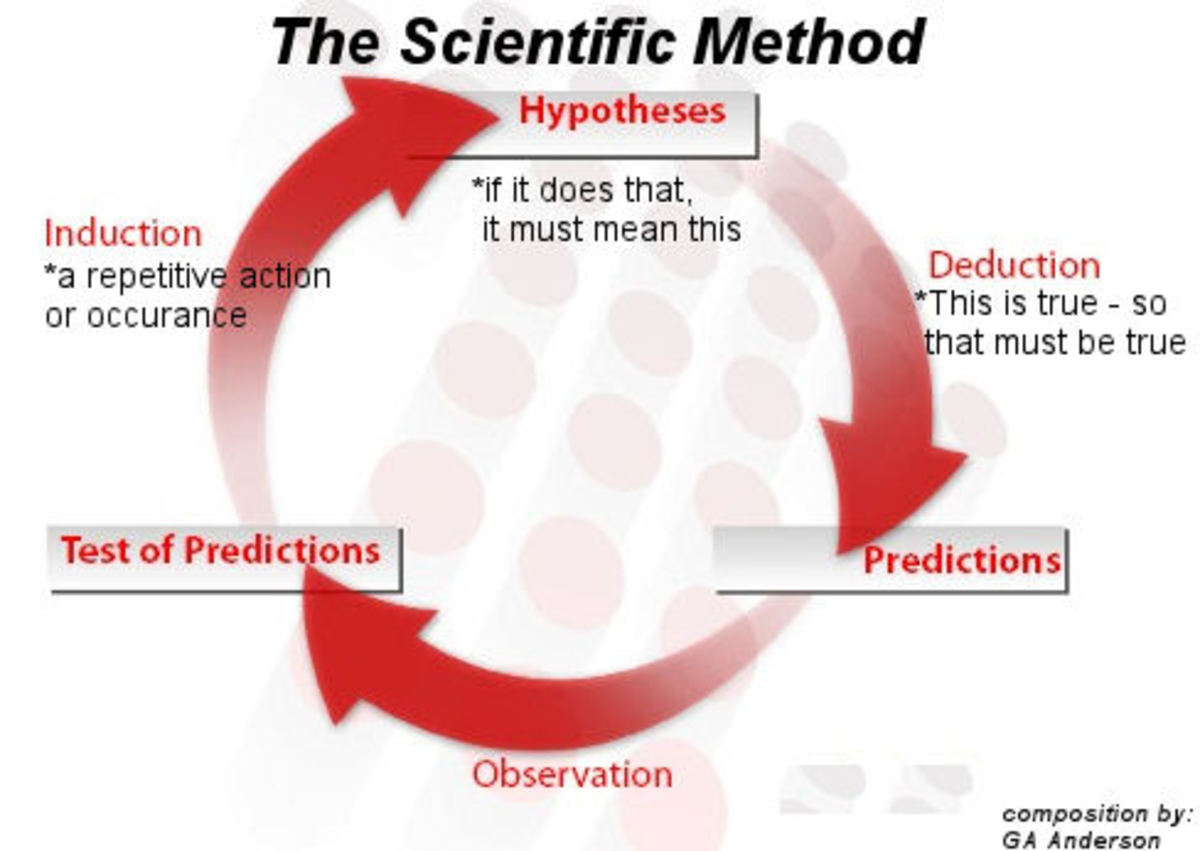

Most Americans don’t know about the Scientific Method. The Scientific Method involves asking a question, developing a hypothesis, testing the hypothesis using experiments, and analyzing the results to find out if the hypothesis is correct or not. Essentially scientists try to falsify their hypothesis. If the hypothesis isn’t falsified, other scientists will try to replicate the results. Further studies may find that the original study was wrong. This is what happened with the Mozart study. Scientists publish their results in journals where they can be peer-reviewed by fellow scientists. If a hypothesis can stand up to repeated testing, it is considered to be a theory.

In science, theory has a different meaning than it does in day-to-day speech. In regular speech, a theory is a conjecture or an unproved assumption. In science, if a hypothesis can stand up to repeated testing, it is elevated to a theory. A theory is an observation that has not been falsified.

Conclusion

Everyone has a responsibility when it comes to scientific literacy. The news media needs to be responsible in how they report on science, and not resort to exaggeration and sensationalism.

Scientists need to communicate well to the general public. Popular science writing needs to be encouraged. Scientists like Neil deGrasse Tyson, Brian Cox and Bill Nye do a great job communicating science to the public.

The general public should become more informed about the basics of science and the scientific method. This should start with schools and universities, which must do a much better job educating students in math and science. It is very easy to learn more about science. There are plenty of science books available in bookstores and the library. Science podcasts, such as NPR Science Friday, are available for free on the Internet and the Science Channel has some very good science programming. There is no lack of scientific information. Unfortunately, there is often a lack of desire to learn it.

1. Spatial IQ refers to the ability to mentally manipulate 3d objects.

2. http://www.badscience.net/2005/09/dont-dumb-me-down/

3. http://blogs.plos.org/speakeasyscience/2010/10/17/the-trouble-with-scientists-2/

4. The Big Bang Theory, The Herb Garden Germination, Season 4, Episode 20

This content reflects the personal opinions of the author. It is accurate and true to the best of the author’s knowledge and should not be substituted for impartial fact or advice in legal, political, or personal matters.

© 2011 LT Wright