The American Warrior Caste

On Memorial Day I was reading an LA Times article, US Military and Civilians are Increasingly Divided. One quote in particular jumped out at me. The article quoted a WW2 veteran, George Baroff, referring to the now common phrase, “Thank you for your service”.

“You never, ever heard that in World War Two. And the reason is everybody served”

Many people today often refer to American military as 'warriors'. And that these warriors were experiencing a since of social alienation from their fellow Americans who were not servicemen, is becoming more and more of an issue.

The Traditional View of Warriors

However, I thought it was ironic that traditionally, warriors had always been a distinct class; separated either by blood, privilege, or region. Whether they were samurai, knights, jaguar warriors, or moors, this unique groups’ role was always distinct from the average person and even their rulers. They were the walls that separated the people from their enemies. They were wave that cleansed the land for their citizens to inhabit.

They were the elite and were treated as such. Not quite royalty but not civilians either. To say that American servicemen are in a class of their own is a recent development. What was it that made American Warriors different?

America, as a nation, was formed out of common people, not an elite class. Soldiers from the wars prior to the end of the American Civil War in 1865, came from the common people and went back to the common people. Whereas in Europe and Asia, you were born into the warrior tradition and shaped by it, even in peacetime. World War Two exemplified this American distinction.

Americans largely laid aside divisions of gender roles, race, and wealth, to win to a global war, one that was a long-term commitment. Whether they fought on the frontlines, worked long hours in factories, or supported the soldiers behind the lines, ‘everybody served’. When the war was over and soldiers came home, there was still the social divide, but no one could really play the trump card of being a veteran.

Do you think saying "thank you for your service" is becoming redundant?

The Birth of a Caste

The American soldier started to become a separate class during the 1960’s and 70’s, and not in a good way. The Vietnam War had polarized the American public, with the younger generation rising up in protest against traditional institutions and being drafted; fighting a war they did not feel was their own. Unlike their WW2 predecessors, these soldiers did not return victorious. And when they did they were called "baby-killers".

For many years, Vietnam veterans and American servicemen after the war endured the shadow of that loss. Many felt isolated from their fellow Americans, and to say you served was to be scorned or be stereotyped as a damaged individual, hence the trope,

“You weren’t there man!”

Between 1975 and 1990, Americans civilians were constantly convicted for this treatment. Almost to the point where it became a stereotype with movies like Rambo and shows like Tour of Duty.

That all changed by the first Gulf War of 1990. Americans now rallied to the new cry of “support our troops”. The cries of ‘baby-killers’ disappeared. This became even more pronounced after 9/11, watching men and women take up position along the wall, to guard against the monsters, the terrorists. Enemies who had over the course of fifteen years, become even more distant from the American consciousness as it become more remote. Conflicts in distant lands only made relatable by those who lost someone there, but nothing like the national galvanization of an entire society as a whole, like in the Second World War.

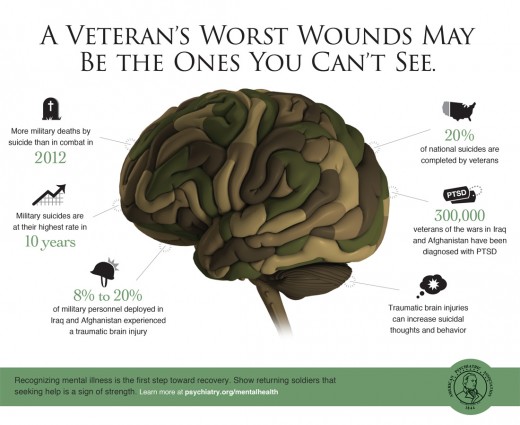

Since then many who have returned, returned not completely whole: losses of body, losses of mind, and so on. And there are few civilians who can relate to that experience or understand its meaning.

An American Trope

Changes in our society and the nature of war have contributed to the creation of the American Warrior caste. The prosperity and technological advances in the 1980’s created an American devoted to consumerism, focused on increasing personal gain and wealth. Military service was still connected to the average American in that most treated it like a job that you temporarily did when you left high school.

The Second Gulf War and Afghanistan however re-introduced Americans to the concept of long-term war. More to the point, the 2003 Iraq invasion was surrounded by controversy over its legitimacy, its handling, and the long term after affects: nothing like its 1990 predecessor. For two generations of Americans raised on increasing personal gain and cynicism, war became more and more something to distance yourself from rather than contribute to.

Those who did choose service crossed an invisible line into a world whose reality the rest of us wanted little to do with. While there wasn’t the public shaming of soldiers as had happened during Vietnam, there was still the huge gap of the two different realities that servicemen existed in. This gap was where the traditional warrior class lived in and what made them distinct.

Distinct and American

I started out with the question, what made the American warrior different from the warrior classes of the past?

It was that it was never a distinct or privileged class to begin with. It was a shared experience on some personal level that even occasionally crossed social divides. Now the burden and risk is no longer shared. Even the social upheaval during the Vietnam War indirectly created a social experience where some aspect of the war or its effects was experienced by all.

“Thank you for your service” I don’t think is meant to be condescending or insulting. However, it would not be surprising if some people reinterpreted that as, “better you than me”. And I have heard some veterans say that they wish people would stop saying it. The modern American warrior may have become distinct from American civilians, but it is still distinctly American. It’s class defined not by the traditional tropes of past warrior cults, but rather by personal experience and the social contrast of self-interest vs. contributing to the greater whole.

© 2015 Jamal Smith