The Importance of Institutional Memory

How Institutional Memory Helped Me Survive

When the pandemic of 2020 arrived, I was prepared. Not because I had advance warning, or because I was a prepper, but because of my family history. I was born in the 1950s. My grandparents and great-aunts had all survived the pandemic of 1918; my grandparents, great-aunts, mother, and father had all survived the Great Depression and the rationing of World War II.

It was their stories of survival that gave me the knowledge that I would not only survive the pandemic of 2020 and its aftermath, but the specific skills that they had developed that had me ideally placed to weather this crisis with flying colors.

The "Spanish Flu"

My grandparents and great-aunts were all teenagers when the waves of the so-called "Spanish Flu" swept the country and the world. They told stories at practically every family get-together, eventually, of how they survived: how they prepared and stored food, how they entertained themselves, how they cared for the sick in their family, how they earned money when everyone around them was dying.

So when news of the COVID-19 pandemic broke, I immediately took stock: food, medicine, staples, access to telephone, bank accounts, mail, and the like. I looked at my skill set: cooking, sewing, being able to write, and having enough projects to keep me occupied during long periods of isolation and boredom.

I planned out my days and projects, planned my meals weeks in advance, and took inventory of what was likely to be used up soon and need replacement. I own my own business and took a hard look at my finances and what help would be available to me, and planned for expenses for the next year: exactly how much I would need for rent, food, utilities, insurance, and other essentials.

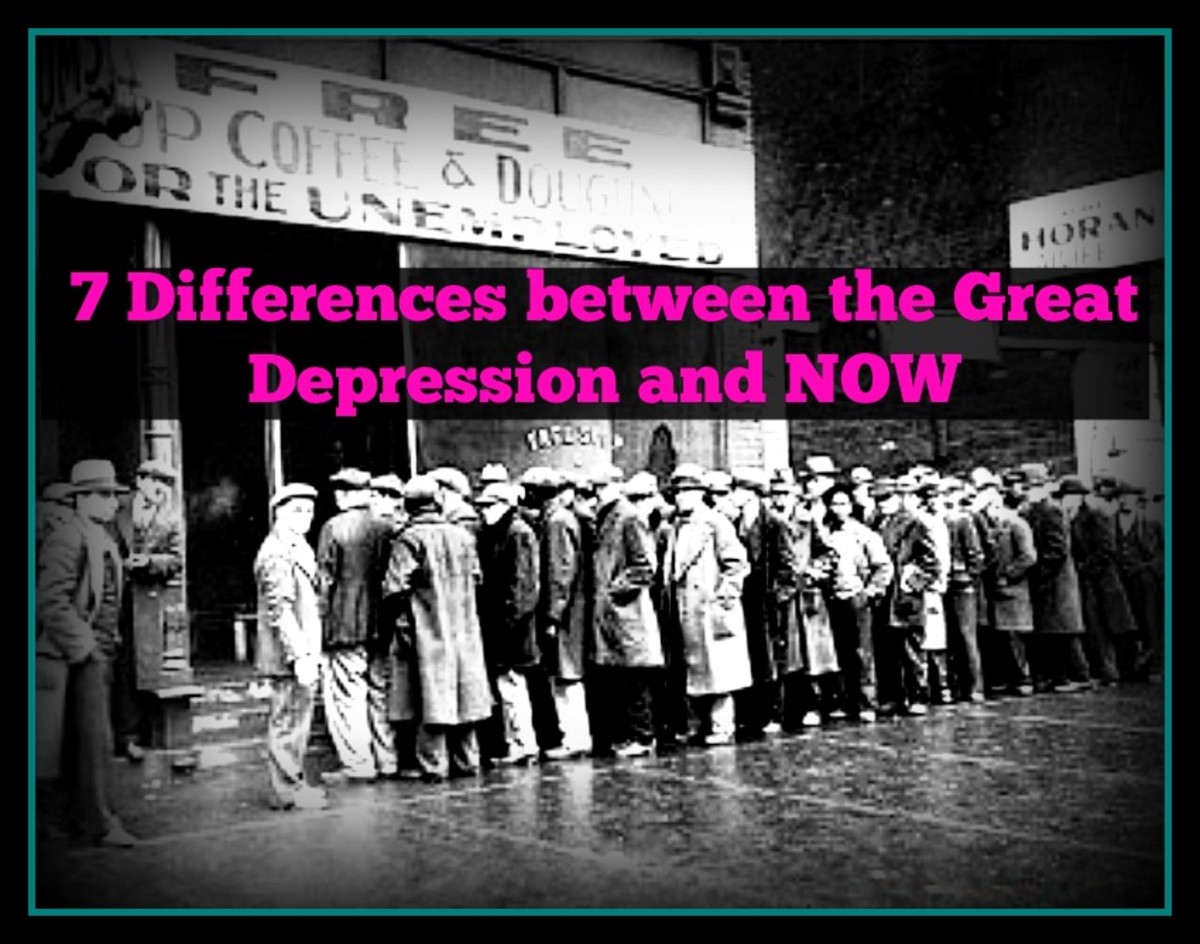

The Great Depression

All those family members, plus my mother and father, had also survived the Great Depression. Their stories of how they economized and made every mouthful of food and every cent count, and how they dealt with rationing and scarcity, fully prepared me for anything I might encounter, as long as I didn't get sick.

Their stories of the bank runs helped me have the perseverance to get through the paperwork necessary for the EIDL grant, the Paycheck Protection Program, and Unemployment Insurance. The process was long and confusing for all of these, but I remembered that my grandparents and great-aunts had waited in line for hours, so it didn't bother me that I had to try hundreds of times to complete the tasks I needed to do in order to get help. I was not only not bothered; I accepted it as part of the process, because my relatives had had trouble, too.

No food in the stores? That was okay; I could make meals out of what I had on hand and be creative with staples. I knew I was in much better shape than my older family members had ever been, and I was even able to supply some family members with things they needed.

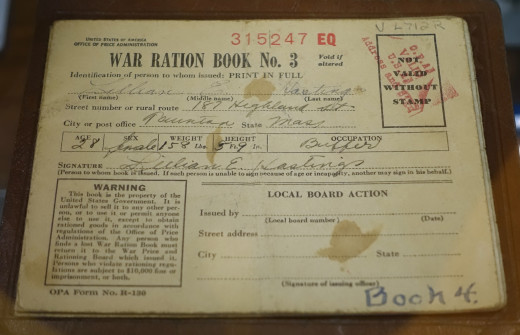

World War II and Rationing

Because I had heard all the stories of rationing, I knew in advance that some items would be in short supply. (I didn't expect toilet paper, but I had enough on hand to last the immediate shortage, and even gave some to friends who were running short.) I stocked up on things that would last a long time: canned and frozen foods, dried staples like rice, beans, and pasta; olive oil. I had spices on hand and plenty of experience cooking foods that would last a long time if frozen, make plenty of good leftovers, and be cheap to prepare. I expected that I would have to find workarounds for various recipes or find new way to use various foods. I even dehydrated a few fresh items (thinking back to my grandmother's stories of canning and dehydrating).

My Friends Weren't Prepared

My friends are of a similar age, but their parents and other relatives did not tell them their stories because they wanted to "let kids be kids." When our county went on lockdown, my friends didn't know what supplies to buy; what avenues they could take to earn money, how to cook with what food they could find (or even how to cook at all), how to make scarce items stretch farther. They called me and talked for hours because they were bored, even with access to the internet and Netflix. They had trouble navigating the red tape for receiving help and couldn't manage to live on the financial help they did get.

The Difference was the Institutional Memory

The stories made all the difference between us. I was never bored; I never ran out of anything I couldn't do without; I always had plenty to eat, even when the store shelves were almost bare. I survived without Netflix, even.

I was able to weather the pandemic in good shape, because I had stories: stories of stores being bare; of killing guinea hens and lambs in the back yard; of trading ration stamps; of saving money by cooking large meals and freezing them; of eating beans for weeks on end; of doing without in dozens of small ways. I knew that if all my family members had survived such hardships, I could too, and I could draw not only on my own resourcefulness, but on their examples of ingenuity.

And that is the importance of institutional memory. Yes, the internet can tell you how to do something, but it cannot give you that personal connection of survival in tough times, or an emotional connection to survival skills you may need.

Resources

While there is no real substitute for institutional memory, some of the lack can be made up by reading biographies and autobiographies of people who have survived similar situations. Newspapers from the 1918 pandemic and the Great Depression ran personal stories, too.

But the important lesson we must all learn from this crisis is that we must preserve our own memories of dealing with this pandemic to hand down to others. By passing on our stories to others, we help to prepare them for whatever crisis may come next.