The Poorest of the Poor

A Call to Haiti

It was probably not the safest time to be traveling anywhere, but I was determined to go ahead with my mission trip despite the post-September 11th warnings for Americans abroad. I had been to Haiti the year before with the same group, and the plans for a return trip were made at least six months in advance. Tickets were booked; I was scheduled to be on vacation, and there was no way I was going to change things at the eleventh hour.

“You should check out CNN,” my husband told me in a very serious tone one evening in late December, 2001. “There was something on the news today about an attempted coup in Haiti, and I didn’t get the full story,” he added.

I found a short article online and wasn’t comforted by what I read about the event. Apparently, an anti-Aristide group had launched an attack on the presidential palace. They were unsuccessful in their coup attempt, but the episode left me shaken. My medical mission trip was only a month away, and we would be traveling into the heart of political unrest. Americans were already targets of terror all over the world, and I just wasn’t sure that I should be tempting fate.

My family shared that fear, but when it appeared that the US State Department was not going to bar travel to that country, we all agreed that I should go ahead and make the trip. On my first visit to Haiti in 2000, I met and worked with a Mexico-trained Haitian OB/GYN clinic doctor. Manita taught me about the language, the culture, and the catch-as-catch-can medical care that was the norm there in a small town outside of Port au Prince. We had exchanged emails throughout the year following that initial trip, and she was counting on my return. “I’ve lined up some patients for you to see,” she said in one of her messages. “There’s a lot of cervical cancer, and other cases for you.”

I couldn’t wait to get started, but first, I had to get there. The group that I traveled with consisted of seasoned veterans of medical mission trips to Haiti. The leader, an ophthalmologist, was completely undaunted by the volatile political atmosphere in that country and around the globe. His experience gave the rest of us comfort as we traversed the obstacle course of international travel. The trip from North Carolina to the hospital in Haiti ended after about 20 hot, dirty hours. It didn’t look that far on the map, but it might as well have been a trip to another planet.

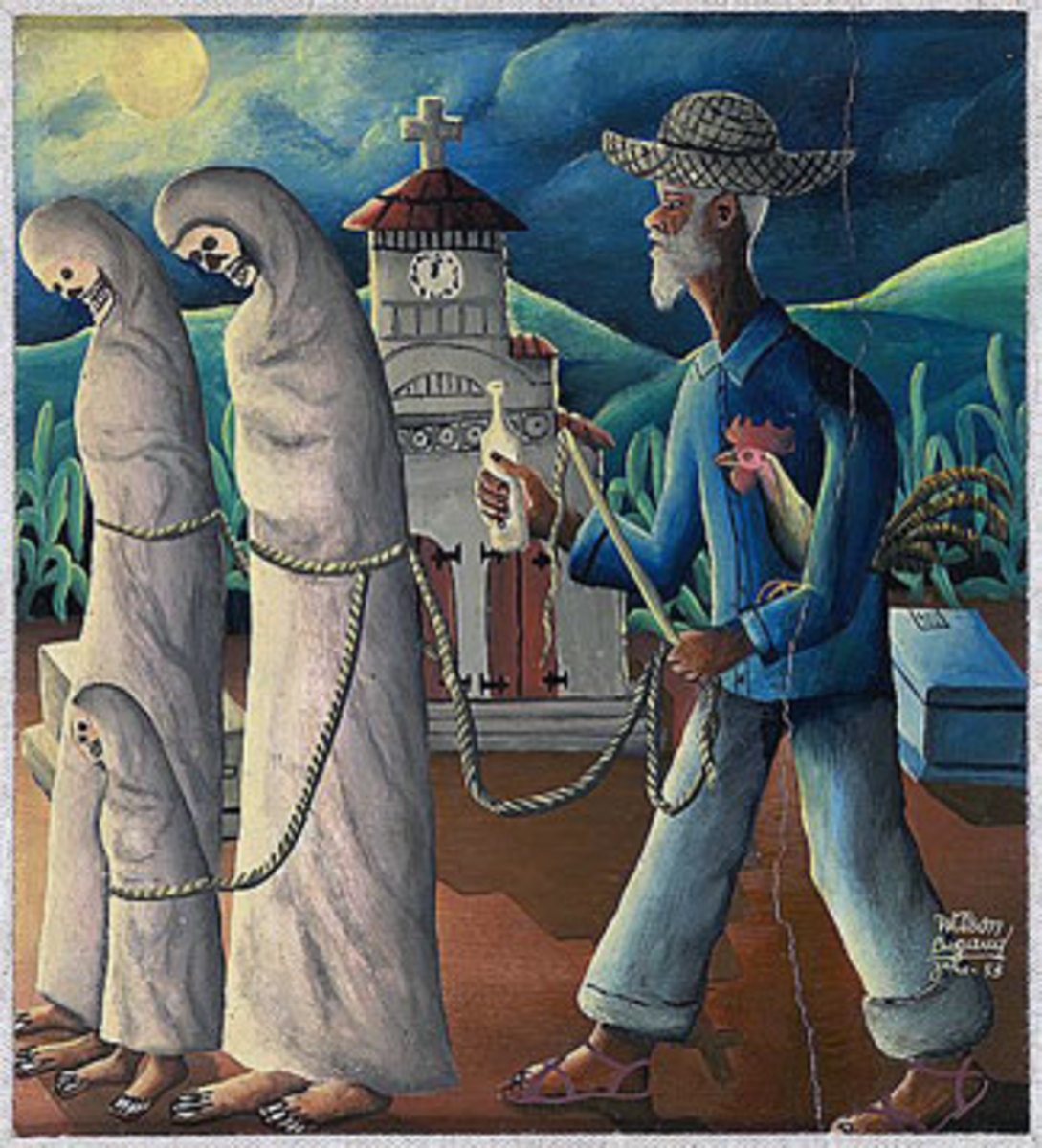

I certainly felt like an alien once I got there. The language barrier is wide, and although the official language is French, very few Haitians use it. Most of them speak Haitian Creole, and I hadn’t a prayer of learning much of that in the short time that I was to be in the country. Nevertheless, Manita insisted that I learn at least a few phrases and be able to address the women in their native tongue. After my first fifty patients or so, I managed to be able to understand their chief complaint and tell them to undress and sit on the exam table. I thought that was pretty good, but I could sense that Manita was under- whelmed by my linguistic skills. She tolerated my pathetic attempts to converse in Creole, and we managed to share a few laughs together amidst the misery of extreme poverty.

The hospital’s gynecology “clinic” consisted on a tiny, closet-like room with no windows and no ventilation. The heat was stifling, and there was simply no way to afford any privacy to the patient. Sometimes there were two women in the room at the same time talking over each other as the nurse triaged one and the doctor took care of the other. I still can’t believe that any good was accomplished in the face of such chaos, but we managed to see about fifty women each day in that one little room.

Manita was not exaggerating when she spoke of the huge problem with cervical disease, but I soon discovered how right she was. Invasive cervical cancer was rampant in this population of underserved women. There is no such thing as routine cervical screening in Haiti with Pap tests or human papilloma virus testing (HPV), something that we take for granted in this country. Many of my patients there had traveled for one or two days from the mountains only to be told that their problem was well beyond my capability to heal. I had brought electrosurgical technology with me from the States, and I did use it on some of the women with moderate and severe precancerous disease. Those were the lucky ones whose disease was detected in the early stages. As for the others, the language barrier didn’t shield me from the hopelessness in their eyes as Manita translated their diagnosis.

“What did you tell her?” I asked my Haitian friend after an advanced cervical cancer patient left the room. “I didn’t tell her that she’s going to die soon. I only told her that maybe she can get some help in Port au Prince.” I confronted Manita with the fact that there is no radiation therapy available even in that large city, and she admitted that this was true. “Still,” she said, “maybe there’s something they can do there.” We both knew that even if something could be done, the lady had no money to get any treatment.

Even well before the massive earthquake in 2010, the Haitians were the poorest of the poor, those that came to my clinic with nothing but rags for clothes. I was told that it is culturally important to dress in one’s finest apparel when visiting the doctor, so I could tell when a patient would or would not be able to afford any medication that I prescribed. The hospital charged them a fee to be seen even though my care was free. I hated that, but that was the way of it. The pharmacy was limited, and I was glad that many of the meds I needed came with me from home. Pharmaceutical companies had donated much needed birth control pills, antibiotics and other useful items, so I could give them away. Unfortunately, the word of free medications spread like a forest fire, and by mid-week, I was swamped with patients seeking freebies. Even the clinic nurses were hitting me up. I didn’t mind, and I tried my best to make time to take care of them as well.

One afternoon, I was wrapping up my clinic and heading back to the austere hospital guest house. As I passed the operating room, a Haitian OB/GYN surgeon hailed me to step in and help with a patient that had just come in from the mountains. “She’s been walking for the last two days and look at this,” he said, pointing between her legs as they flopped apart on the rickety stretcher. I was horrified. I could feel the tears welling up as I realized that I was looking at the blue arm of her lifeless baby protruding from her body. “We have to do a C-section right away,” he said, hoping that I would volunteer to do it with him.

Without hesitation, I scrubbed and contemplated the hellish nature of my mission. What was I doing here? I couldn’t really help these people, could I? The Haitian surgeon didn’t give me time to rethink it. He beckoned me into the operating room (that term is loosely applied here), and we went to work. The operating rooms are full of old, broken medical equipment, and improvisation is the name of the game. You never know what suture will be available or what instruments will be useable, and there is seldom a meaningful way to communicate with the scrub nurses. I used hand signals for the most part. The Haitian surgeon spoke very broken English, and we got by.

After opening the abdomen, I could immediately tell that the baby had died a long while before. The patient had been laboring with the baby in a sideways position, and there was no way she could have expelled the baby vaginally on her own. Once she realized her problem, she brought herself down the mountain in search of help. I found out later that she had four or five children at home who were depending on her to survive. I never dreamed she would.

“She’s got a ruptured uterus,” I told the Haitian doctor. “We’ll have to do a hysterectomy.” I showed him the large hole on the back side of her uterus that was bleeding briskly, and he didn’t need to know much English to understand the grave consequences for the patient. Her belly was full of infection already, and I was dubious about the availability of appropriate antibiotics. The odds were stacked against her. As I prayed silently, we took out her uterus and flushed away the infection with as much sterile water as we could get. I had participated in multiple other operations in Haiti prior to this one, and there never seemed to be irrigation fluid until now. Perhaps it was the prayer. “Do you have any antibiotics that we can give her,” I asked my surgical partner. He indicated that he could get something that sounded like it was fairly powerful, and I was relieved.

When I made rounds on this unfortunate patient the next day, I was astounded at her appearance. She looked wonderful! I simply couldn’t believe that this woman could be alive and doing well after such a catastrophe. She was severely dehydrated, anemic and full of infection by the time she reached help, and I believe that her survival was nothing short of a miracle.

After that incident, I continued to be very busy managing the daily misery of the clinic patients, and so I hardly had time to think of any potential danger to myself or my group. The political nightmare was ever-present in Port au Prince, but that was far away and of little concern to me or my patients. They were engaged in the day to day struggle to survive, and I will forever be in awe of their courage. Before I departed for my comfortable life back in the States, I gave a small present to my Haitian doctor friend, Manita. It wasn’t much, but the silver angel pin seemed to resonate with her. I wanted her to know that I considered her to be an angel on Earth because she worked so diligently under such adverse conditions, and then I made sure that I said good-bye to her in Creole.