The Problem of Bigness

When Management is Separated from Ownership

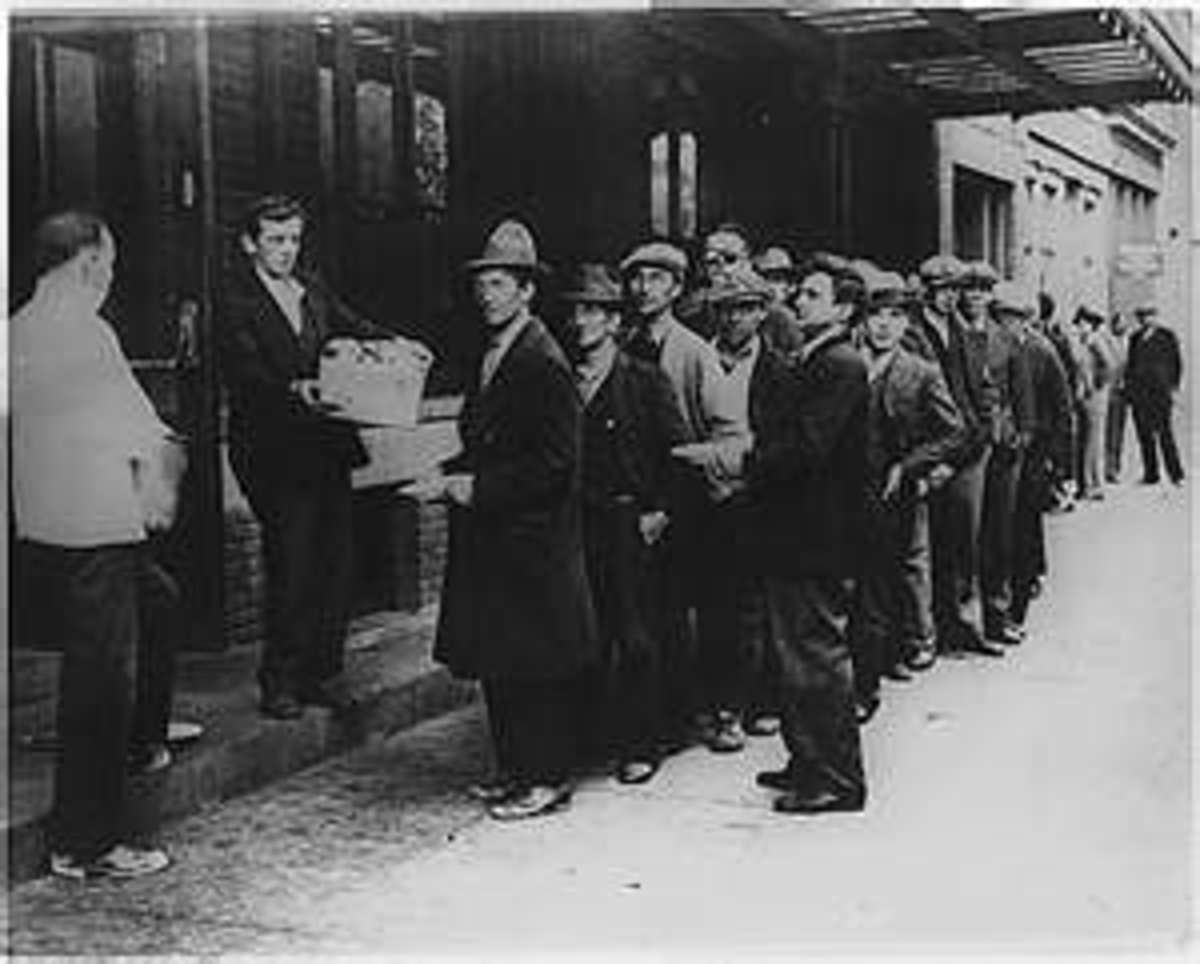

It is rational to think that private industry is inherently more efficient than the public sector It’s largely a matter of incentives. If a private company runs itself efficiently and has a viable business model, it will be able to turn a profit. But if it messes up badly enough or finds inadequate demand for its goods or services, it will go out of business, and the economy as a whole will be better off. If competition is allowed to play itself out, only the well-run, economically relevant companies survive. With government, however, there is often no incentive to spend money wisely. Revenue generally comes from tax dollars, not from income earned as a result of performance. If government agencies blow a lot of money, they will usually stay in existence in spite of their incompetence, low demand for their services, or any other financial weaknesses. And if the government steps in to bail out failed businesses, they weaken the economy over the long haul.

This belief in the superiority of the private sector, however, can sometimes be more accurate in theory than in practice. It is based on the seemingly obvious assumption that people running businesses are concerned with the long-term success of their operations. With small companies in which the owners and managers are the same people, the interests of the managers and the businesses are lined up very well. If a company is able to grow and thrive over the long haul, the people running the operation directly benefit. But if a business evolves into a large corporation, there will often come a time when the managers and the owners are no longer the same people. And in this situation, the managers of these complex operations will primarily be thinking about their personal, short-term interests instead of the long-term interests of the corporation. The quarterly profit reports and the current stock prices of the corporation become a higher priority than the company’s ability to stay competitive and financially viable over the long haul. Since the people in upper management may not be planning to stick around for too long, and they are judged on the basis of current performance, the plan is often to keep those high salaries for as long as possible, jack up the prices of those stock options, and bail out / cash out at some point in the future, moving on to the next opportunity that turns up. (And for fired CEOs who have long-term contracts, the severance package is often more than enough to retire very comfortably.)

The recent financial crisis may be the ultimate example of the consequences that can arise when managers are not truly invested into the long-term health of the companies in which they work. In a purely economic sense, packaging bundles of bad mortgages into mortgage-backed securities and selling these shaky instruments to investors was pretty foolish. But for people only thinking about their short-term self-interest, it made perfect sense. The sale of these derivative products was an easy way to generate quick cash, increase the profits of financial services companies, and earn big bonuses for those setting up the transactions. And if the people running these operations were smart, they were careful to put all of this money away before the bottom fell out. And if they were really smart, they cashed out whatever financial stocks that they had before the companies reached the brink of disaster. When the bottom fell out, after all, no one asked the brokers to return the bonus money or the profits from sales of stock. So if a person was driven purely by self-interest, this was a potentially brilliant operation. The fact that many financial services companies either went under or received massive amounts of bailout money was of secondary concern. The interests of the companies and some of the people working for them were clearly not in line.

So what can be done about this situation, particularly with a financial sector that can be manipulated in so many ways and on which all of us are so economically dependent? What can be done to stop bankers from thinking primarily of short-term self- interest, even if these interests threaten the long-term existence of the companies in which they work? Some cry out for regulation, but hiring flawed human beings to watch over the behavior of other flawed human beings is not a foolproof plan. And with limited government resources, an incredibly complex financial system, and a continually revolving door crossed by people changing jobs from banker to regulator to banker once again, government regulation may never be enough to stop risky behaviors that threaten the system. In the end, the fundamental problem may be bigness. If a bank it too big to fail, and by its nature is filled with employees who may not have its long-term interests at heart, then it is too big period. By nature, a capitalistic, corporate economy will inevitably have failed businesses. It is in none of our interests, however, to have the failure of a few mega-banks drag us all down with them. Big may sometimes be necessary, but it is not always better.