Being Black in America: Confronting Truth, Injustice, and Healing Through Time

As a community—without a specific African cultural heritage beyond slavery and having to depend mostly on one another for generations—Black Americans must begin to purge the mindset of Black against White. It’s not easy. History is a harrowing, emotive storm of accusation, hurt, and blame over what some Whites have done for the sake of personal prosperity at the expense of many Americans of African descent.

Yes, Skin Color Matters: Not in the Way You Think Though

The Black communities of the United States must not disregard their shared heritage as descendants of slaves and second-class citizens by attempting to assimilate into the majority culture through a pretense that color does not matter. No. There must come acknowledgment and acceptance—deliberate and voluntary—that will lead to clarity of purpose and begin the long cultural and racial healing Americans must endure.

Should Black communities work diligently to assimilate into the broader American culture? Yes—but with open eyes and open hearts to both the truth of the past and the progress of the present. Assimilation must be a choice—one made in pursuit of unity with a culture that espouses freedom, opportunity, and representative government.

Like the Forefathers of this august nation, Black Americans can choose to unite under one name while still honoring the triumphs over historical oppression. That name is American.

Love is NOT Limited to a Race

White America—the cultural aspect of a White America—is a choice purposely forged with the benefit of continuous ties to homelands never interrupted by forced cultural purging.

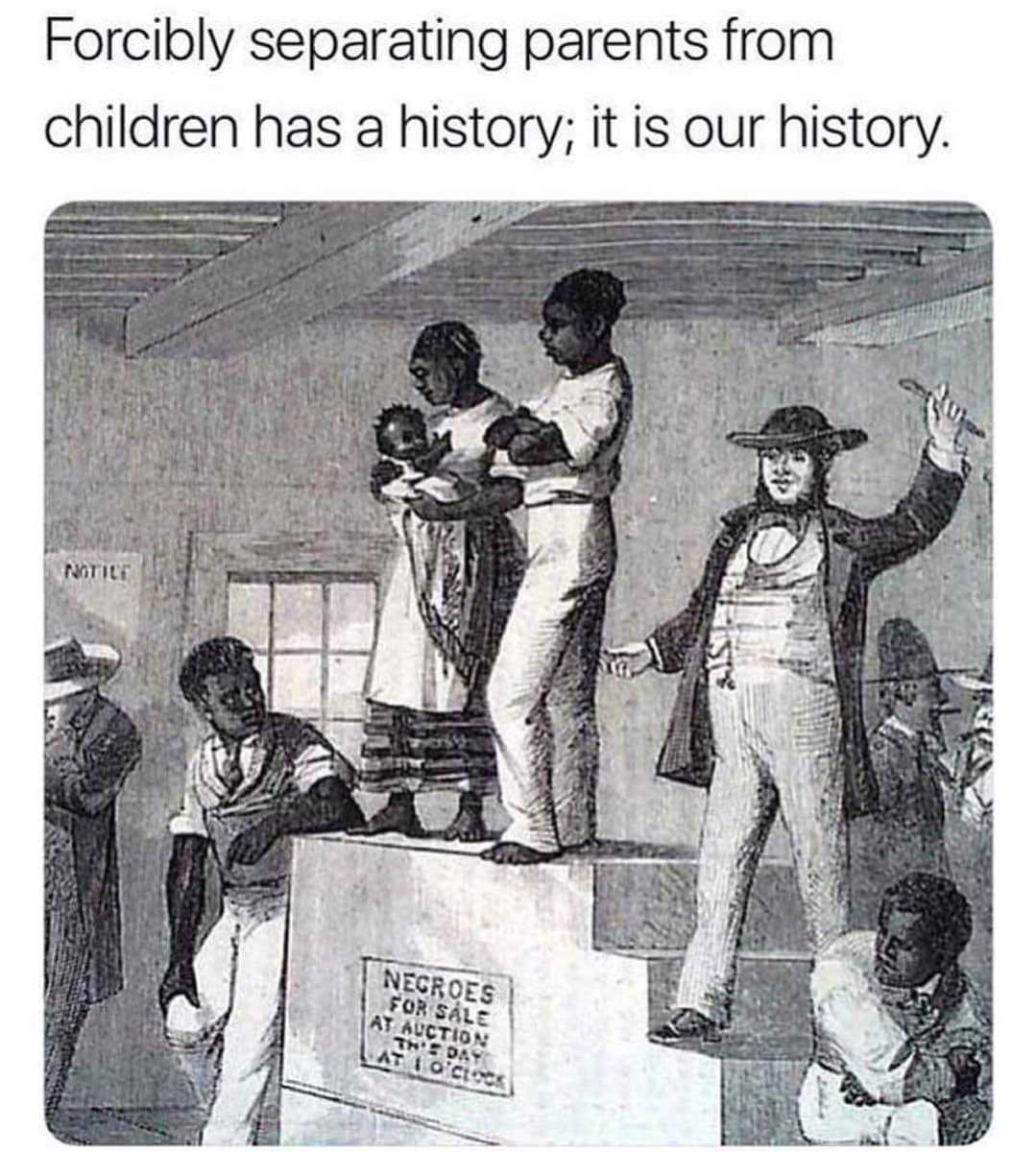

Most Black Americans have no choice but to accept the ambiguity of ancestral connection to Africa and the reality of livestock-like breeding in America. Many descendants of American slaves are still attributed stereotypical physical traits: tall, large, muscular men and thick, wide-hipped women. At one point in history, such descriptions could accurately depict the enslaved people that slavers selected and bred for labor. This may contribute to the lingering assumption that Black Americans excel in sports at disproportionate rates.

This false correlation also once served to justify the stereotype that descendants of American slaves were inherently intellectually inferior—a premise rejected by modern psychology. No scientific evidence supports this claim, though it has persisted culturally. Fortunately, such stereotypes are gradually diminishing alongside their physical caricatures.

Black culture is uniquely tied to America since that group is alone having been forced to the States and forced to give up culture.

Why Can't Blacks Just Get Over It?

This subject is far too complex to be answered fully in a single section of an article—but here is a beginning.

Because of the cultural effects of slavery and generations of persecution, Black individuals must navigate a cycle of introspection that is common among all marginalized groups whose composition doesn’t reflect the dominant cultural ideal.

To answer the question directly, before diving into examples:

-

Not enough time has passed.

-

Not enough healing has occurred.

-

Not enough societal shift has taken place.

For instance, a White man might have a bad day at work and speak curtly to a Black store clerk. The clerk may think, “Did that person behave that way because I’m Black?”

Because of the inherited cultural implication passed down from generations of oppression, these thoughts often flash through the minds of many Black Americans (and others from marginalized communities). Ideally, such questions are filed away by reason and rationalization—hopefully, with a positive interpretation. But the fact that the question arises at all shows the lingering tension.

The same mental gymnastics applies to women—especially minority women—who must add gender to the equation of internal reflection.

This kind of introspection applies to anyone who does not align with the dominant culture, including members of the LGBTQ+ community, obscure religious groups, and others. But it is especially true for Black Americans, whose cultural identity is uniquely tied to the United States by force. Members of this group alone were brought into the country through enslavement and stripped of their ancestral culture.

All of this translates, subjectively, to a collective perception: that the prisons are full of Black men and women because Black people—regardless of modern access—still feel they must fight through the American system. Even with a more level playing field today, the trauma and suspicion remain.

Barack Obama became president, some argue, because they—White people—wanted Black Americans to stop using racism, especially the hidden and conspiratorial kind, as an excuse for not getting ahead in society.

There exists a wide spectrum of opinions among Black Americans. Those who think differently—who break with the predominant cultural narrative—may receive negative attention as individuals who are either denying their heritage or unaware that they are doing so. In disassociating from the social aspects of African American culture, they risk being perceived as hurting themselves or betraying their own.

The stain of slavery lingers. It limits the modern descendants of slaves, or at least has the potential to restrict them. Freedom of movement, thought, and philosophy are still hard-fought in many communities. Even intellectuals often find themselves burdened with the worry that law enforcement will treat them disparagingly for the “crime” of having too much melanin and the wrong texture of hair.

White Americans, generally speaking, do not need a race with which to identify. Black Americans, by contrast, often do—collectively more than individually. Of course, a growing number have adjusted to mainstream American society due to their cultural experience, but the broader social need remains.

Again, not enough time has passed since the Civil Rights Movement. Perhaps in three to five more generations, Black Americans will begin to think about race the way most Caucasians do: as something that does not define their heritage.

Yet it remains remarkable that there exists an ethnic group in America whose identity was forged entirely on American soil—a uniquely American creation.

All Americans have struggled to some degree for the right to be in America. The United States of America is culturally diverse with groups that successfully etched a place in the American landscape.

Moving Beyond the Past

It is not the purpose of this article to persuade Americans of African heritage to forget the struggles of the American slave. On the contrary, Black Americans must remember—and embrace—the shared American heritage of struggle.

All Americans have, to some degree, struggled for the right to belong in America. The United States is a culturally diverse nation, shaped by groups who have each etched a place in its landscape.

Whether that struggle began with a fight for equality or a battle for independence, all Americans share one enduring trait: the will to persevere until the work is finished and the situation brought under control.

American descendants of African slaves are distinguished in the nation’s story as captives and slaves, yet they also share in the glory of overcoming—alongside other groups. Granted, the descendants of slaves may have more to overcome because of an especially oppressive past. But such a history does not constitute a handicap.

The determination of the change-makers of the past lives in the genetic core of all Americans. As diverse as America is, it is our common heritage that makes us great—not diversity alone.

Previous Article of The Truth About Being Black in America Series

- Being Black in America: A Raw Perspective

Slaves were treated as livestock, with their humanity stripped by slavers. This article explores how early American slavery shaped lasting cultural attitudes toward race, and the lingering myths that still cloud public understanding.

This content is accurate and true to the best of the author’s knowledge and is not meant to substitute for formal and individualized advice from a qualified professional.

© 2018 Rodric Anthony Johnson