The Variable Man: The Arab Spring and the Role of the Small Individual In Shaping History

Seen in hindsight, the events of history can seem orderly, even predictable. But the truth is that the great tides of history are often started by what at the time would have seemed an insignificant event, by people no one ever heard of. The firestorm of revolution that led to the so called Arab Spring and which are still playing out in the battlefields of Syria, started with a small spark in an obscure town in Tunisia, a place and a man no one ever heard of, until they changed the world.

Hosni Mubarak, the decrepit 82 year dictator of Egypt Hosni Mubarak had been in power since 1981, longer than any previous sultan or king under the Ottoman Empire. He was a king in all but name, cloaking his regime with a veneer of legitimacy through rigged elections, and if the Wikileaks cables are to believed, through intimidation and harassment of dissidents. In one incident an amateur poet was prosecuted and sentenced to three years in jail when a search of his house revealed that he had written an unpublished poem critical of Mubarak. All of a sudden, Mubarak's seemingly iron grip on his country was shaken and then broken as hundreds of thousands of his subjects gather in the streets chanting "Mubarak Must Go!" And very soon he will go. His son, once thought to be in line to succeed Mubarak, has already fled to London with his family.

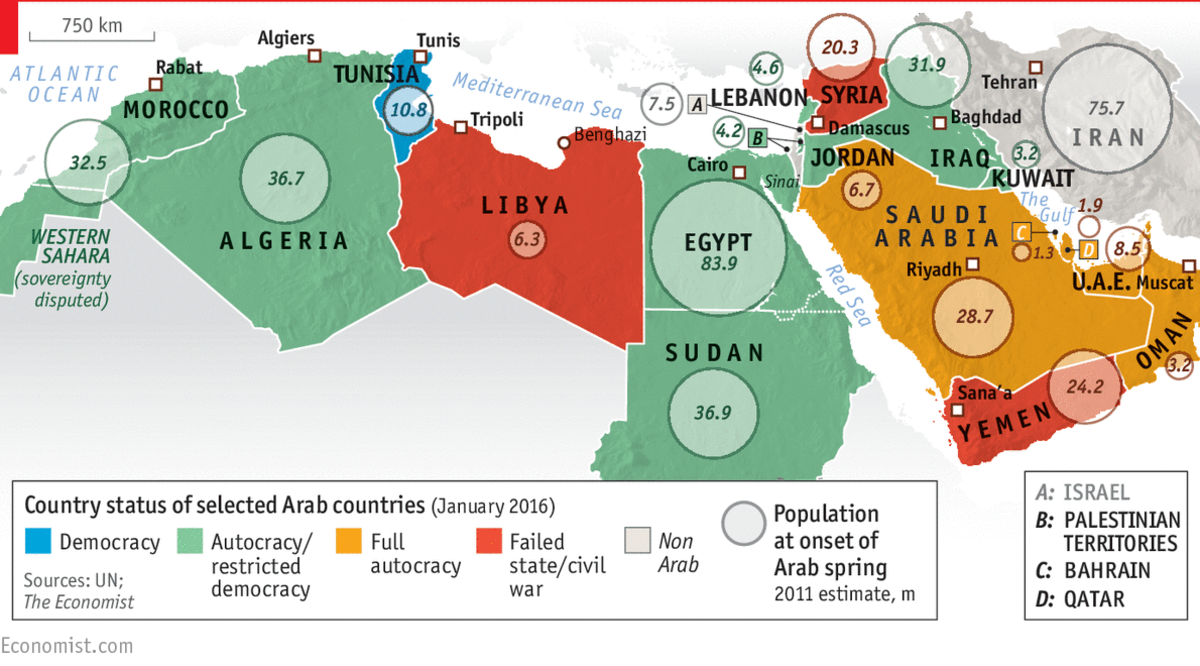

Just a few weeks before the Egyptian protests began, the corrupt kleptocracy that ran Tunisia was chased out of office by angry crowds. Tunisia was the first domino that has sparked a wave of protests and defiance in the Arab world. Egypt is tittering on the brink of revolution. And there have been protests in Sudan, and other Arab countries. After Egypt's regime fell, the spirit of revolution continued to spread throughout the middle east: in Syria, in the gulf states, in Lybia. In some cases, the tyrants ran away, or made concessions, or where overthrown, or in some cases stamped out the revolutions that threatened them. The revolution did not succeed everywhere, in places such as Libya there is mounting evidence that the replacements are just as bad as the monsters that they overthrew.

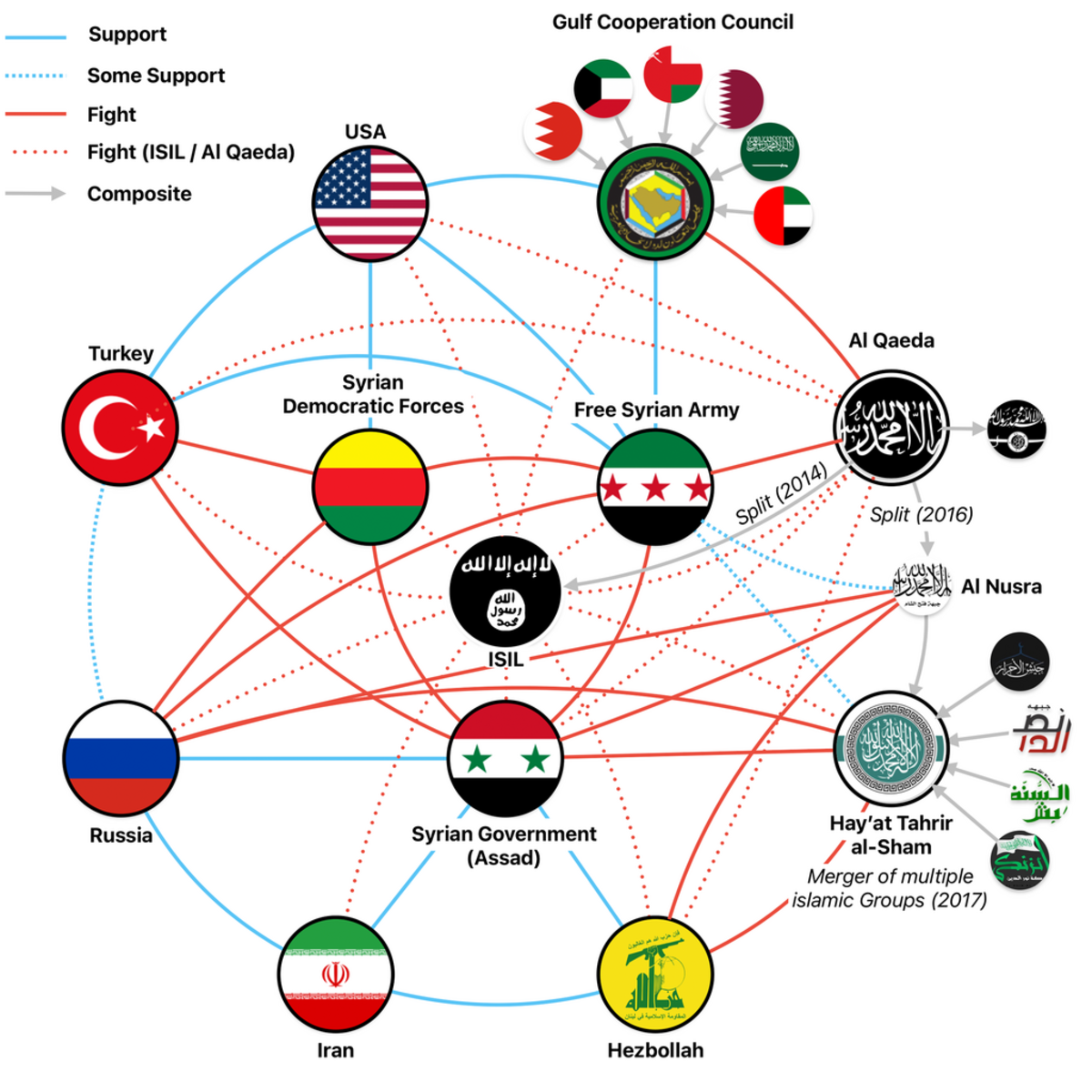

Hopefully the Arab Spring will usher in a new era of freedom and democracy. But more than likely, the revolutions that started out with such hope will be betrayed and the brief freedoms gained by the people will be replaced by strict Islamic law, virtual slavery for women, and a repression similar to what happened following the Islamic Revolution in Iran. In Syria, both sides of the conflict are bad: the murderous Assad dictatorship versus the murderous terrorists intent on imposing Sharia law. When the rebels win, secular Syria will be dead and the Christians and other minorities that live there will have to flee for their lives.

What Caused the Arab Spring and the Revolutions?

How did we get to this point, this critical turning point in world history when the fate of the entire region and possibly the world hangs in the balance? Decades of corrupt and inept rule by dictators, rising food prices, high unemployment, all certainly contributed to the people's sense of discontent and hatred for their governments -- but these conditions have existed for years. What then gave spark to these popular uprisings?

There are some that would say that the Wikileaks cables exposed the corruption and evil of the regimes and opened the people's eyes. But in truth anyone who lived in Tunisia or Egypt knew what how corrupt, lawless and oppressive their regimes were. It is paternalistic for us to think that it took some cables generated by American consular representatives to make people see what they had been experiencing their whole lives. No, it was not media starlet Julian Assange that fanned the flames of revolution.

The spark for the revolution, quite literally and metaphorically, came from a man whose name you have never heard of. A nobody, trying to eek out a living in Tunisia selling vegetables on the street from a small wheelbarrow. He had no permit to do so. He could not afford to bribe the police to look the other way. One day, the police tool Mohamed Bouazizi's only means of support away from him. When he went to reclaim his goods, a female clerk in the municipal office spat on him, and threw his scales away. Then her colleagues joined in beating the young man. This is the kind of government and society that Tunisia was and most Arab countries still are.

Bouzazi asked to speak to the governor in order to complain. Of course the governor had no time for him.

So in desperation and protest Bouzazi went to the pubic square in front of the municipal office drenched himself in gasoline and then set himself on fire. His suicide reminded the people of Tunisia of their own humiliation. They came out by the thousands, and overran the riot police sent to stop them. Soon the Tunisian government was fleeing on their private jets like rats abandoning a sinking ship.

The new media of Twitter, Facebook as well as Al Jazeera brought the news of their success to the rest of the oppressed Arab world and the fire began to spread - what it will consume and what will remain after the conflagration remains to be seen.

The Fighting in Syria

Which Will be Next Arab Dictatorship to Fall?

The Variable Man

The fact that this world changing event might have been triggered by an unknown street vendor living and drying in a small town in Tunisia that most of us may never have heard of may seem incredible. But this has been the way of the world for all of recorded history - true change comes not from predictable patterns or developments but from the unpredictable and unknown Variable Man, the man or woman who does not fit within the system and thus can effect true change.

The great science fiction writer Phillip K. Dick wrote about this in his short novel The Variable Man, published in 1953. In the story, an upstart earth seeks to expand beyond its solar system but it is surrounded on all sides by the decaying empire of the Proxima Centauri which blocks humanity's access to the stars. A sort of cold war exists between the two antagonists, but open war has not broken out because massive computers on both sides calculate that neither is strong enough to defeat the other. The humans have a plan, however, they plan to create a faster than light missile that will materialize inside Proxima Centauri, causing the home star or the enemy to blow up and destroy the core of the Centuarian empire. At a precise moment the earth fleet will attack all Centaurian outposts and destroy the enemy fleet in a Pearl Harbor style attack. This act of genocidal treachery is justified by the humans as being necessary to ensure the survival of the human race and to ensure its manifest destiny to rule the stars.

The plan is about to go into effect, when the Variable Man enters the equation. In the story, he is a human from the past living in America before World War 1. He has been brought to the future as part of one of the military's experiments aimed at finding ways to defeat the Centaurians (the idea being that if armed forces could be sent back in time they could defeat the Cenrtaurians before their military capabilities were sufficiently developed to resist the humans). The Variable Man is a sort of mechanical genius; in a society where everything is disposable, he can intuitively understand how to fix things. In the end, in a somewhat unbelievable plot device, he is given the chance to fix the Terran doomsday weapon. The weapon is unleashed but the Centaurian star does not explode. The predetermined attack by the Terran ships goes ahead but they are defeated and the humans have to beg for peace.

Only later do they discover that the Variable Man had indeed fixed the weapon - instead of a FTL drive that would explode when near any star (making it unusable for manned space travel) he had solved the problem that had prevented humans and Centaurians from achieving faster than light travel. The result was that manned faster than light travel was possible. Humans could now skip over the Centaurian empire's borders and reach for the stars. None of the Terran supercomputers tasked with predicting the likely outcome of all possible options had anticipated this, because the Variable Man had not been part of their equations. He was an outsider, an unknown.

The Variable Man is science fiction, of course, but the point it makes reminds me of what is happening now. The Arab dictatorships are crumbling, the fate of the world is wobbling on the precipice of a new Age of Revolution, all because of an unknown impoverished street vendor in an obscure town in Tunisia, a true Variable Man. It should give us pause to consider that the world we know could be built on such shakey foundations.

Fighting in Syria

© 2011 Robert P