Tulsa Race Riot of 1921

The Rise and Fall of Black Wall Street

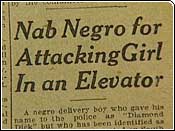

Shadowed by the enlightened intentions of the Progressive era, America welcomed the onset of the 20th century as a nation reveling in the unparalleled growth and development attributed to the sweeping trend of industrialization. The industrial and technological benefits of such an innovative age correlated with a steady increase in the standard of living. Yet, the positive spirit that permeated the land of opportunity was not all encompassing; immigrants, the poor, as well as racial and ethnic minorities faced resistance fueled by those intent of protecting the promising prospects of America’s future.[1]

Structured atop the Progressive mindset was Tulsa, Oklahoma, a new frontier that grew rapidly with the oil wells that served as its foundation. The Euro-Americans that supported the early rise of this city as a primary settlement had, by 1900, eagerly ousted the Native American population, which included tribes of the Creek and Cherokee nations. Rather unexpectedly, the African Americans that had served as slaves in the earlier Indian Territory were left to comprise five percent of Tulsa’s population, a number that would double by 1910, and would reach its zenith in 1921, at 11,000 individuals. [2]

Abandoning any newly pronounced free-thinking, as had been preached for the duration of the previous two decades, the joint European-American populace forced Tulsa’s history to become one better recounted as “a tale of two cities”, as Oklahoma’s boom town fell victim to the promoters of racial bigotry. In the absence of any ethnic cooperation, Whites and Blacks approached the prospects of Tulsa independent of one another, resulting in two fiercely segregated, yet economically successful quarters of town.

It was within this racially hostile situation that the Greenwood District – referred to often by Tulsa’s White public as “Little Africa” - was born.[3] Here, within 35-square blocks -beginning at the intersection of Greenwood Avenue and Archer Street- thrived the highly prosperous Black residential and business community that gained reputation for its self-sustained status throughout the Southwest. Supported by the re-circulation of black money, ample capital and credit provided the necessary stepping-stones towards the construction of “America’s Black Wall Street”.[4]

Many of the neighborhood’s residents held a dual role as Greenwood’s founders and entrepreneurs. They created businesses based upon the needs of its socially circumscribed residents, the first of which was a grocery store at the intersection of Archer Street and Greenwood Avenue.[5] John Williams, a former ice cream factory worker, utilized his mechanic skills to open the premier auto garage in the district. His well-earned wealth was consequently concentrated back into the community through the construction of a confectionary and a theatre.[6]

Meanwhile, O.W. Gurley, a real-estate mogul, owned and operated one of the more prestigious hotels, and assisted the creation of a safe haven for the ostracized African-American populace.[7] Simon Berry, yet another of Greenwood’s earliest proprietors, seized a firm grasp on the neighborhood’s transportation system, which developed from a “nickel-a- ride” jitney service into a bus line that he later sold to the city of Tulsa.

Some individuals, such as Dr. A. C. Jackson, chose to look beyond the heavily rooted allegiance towards the black Tulsan community, and succeeded in not only influencing and benefiting his constituents by his successes, but also bridging the color gap in the racially rifted Oklahoma town. Anointed as “the most able Negro surgeon in America” by the Mayo brothers, founders of the Mayo Clinic, proved that the hatred shared between the Whites and African-Americans were superficial at best.[8]

Yet, it was not solely Black men who could enjoy the advantageous conditions facilitated by Greenwood; a number of women made their fortunes there as well. The most renowned of these is perhaps Mabel B. Little, who opened her first African-American oriented beauty parlor in 1917, continuing the business successfully for the next fifty years. She, as well as her husband, Presley Little, contributed many more services to the district, and gave themselves as instrumental vessels in the construction of Mount Zion Baptist Church, one of the most notable houses of worship in the area.[9]

By the year 1920, the district boasted an impressive array of shops, hotels, restaurants, and gaming halls. Its vibrant streets also held a hospital, public library, two schools, two newspapers, two theatres, and thirteen churches, amongst 150 further commercial buildings that housed grocery stores, doctors, lawyers, dentists, cafés, nightclubs, and other varied enterprises.[10]

On Thursday nights and Sunday afternoons, both days on which black domestic employees of White Tulsans were permitted off, the vibrant streets of Greenwood served the cultural needs of its patrons, as well as their material wants. Within the city’s various dance halls, a rhythmic and soulful sound, later identified as Jazz, had rooted itself into the Black community.[11] Its tone influenced the hearts and minds of its eager audience while inspiring others, such as famous jazz pianist Count Basie, to submit themselves to an entirely new feeling.

The triumph of Tulsa’s African-American population, embodied in their prosperous economy and strong social fabric, may not to have easily translated across the borders of the Greenwood district. Racial tensions that had been exacerbated throughout America’s recent history may have provided ample grounds upon which the White community constructed its resentment towards the rise of a minority group. The antipathy would although remain subtle until the spring morning of May 31, 1921, when the spark of a singular probable incident would be stoked by the flames of ignorance and hatred to become the fire that would rage through Greenwood hours later, leaving in its wake the scorched remains of a community’s spirit, success, and potential.

The initial source of the burning that would later engulf the affluent African-American business sector was embodied in a historically vague incident that occurred at the Drexel Building at 319 South Main Street, located within “white sector” of Tulsa’s strictly divided community. The building accommodated a “colored” restroom on its highest floor, and that required 19-year-old Black shoe shiner, Dick Rowland, to seek out the elevator operated by a young white woman, Sarah Page.

What truly transpired after the doors of the elevator were firmly shut cannot be teased out of the biased accounts that claim to reveal the accurate portrayal of the event. The only consistencies between these testimonies consist of Page’s scream, followed by Rowland’s hurried exit from the building. The remainder of the incident rests in obscurity.

One of the most common versions of what occurred concerns Rowland accidentally stepping on the foot of the young elevator operator, who inadvertently let out a scream. Some of the more extreme versions, which soon thereafter were propagated by the white community, accused the shoe shiner of attempting to rape Sarah Page, who herself vehemently denied such accusations. The voice of the local Tribune newspaper, published soon after the incident, although muted the young girl’s defenses and neglected to take into account the reality of the event.

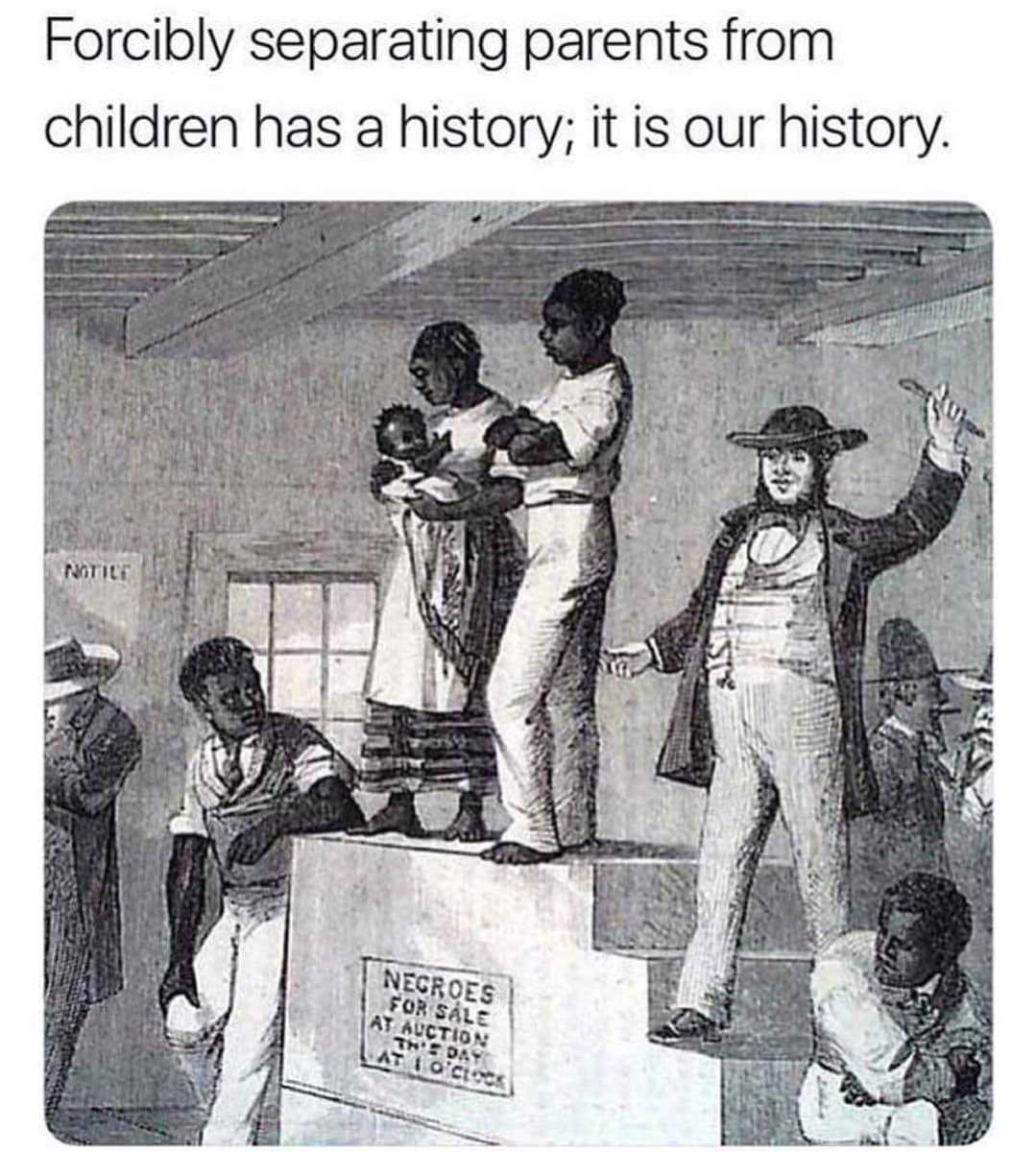

Crowned by a headline reading “Nab-Negro for Attacking Girl in an Elevator”, the front-page article charged Rowland, identified as “Diamond Dick”, with assault, while another “To Lynch Negro Tonight,” claimed the future of the young man.[12] Infused by the fictional renderings of the journal, a crowd of armed white men, many active participants in Tulsa’s local chapter of the Ku Klux Klan, met before the jail in which the incarcerated Rowland resided, driven by the imagined promises given earlier that day by a prejudiced report. [13]

The wave of hatred rushing to drown the incriminated youth was although momentarily quelled by Sheriff William McCullough, on whose conscience weighed the recent lynching of Roy Belton. Belton, another black teenager, had been both convicted and executed by a bloodthirsty crowd for the murder of a deputy of a nearby town. The almost complete absence of police mediation during these proceedings therefore served as encouragement for the protestors who now stood before Rowland’s cell, raving of justice.[14]

The same accounts that had incited the mob had –long before the rabble had organized itself- circulated outside of White Tulsa as well, and in defense of the teenage shoe shiner came somewhere between fifty to seventy-five black men, a majority of which had served in World War I and had donned their faded fatigues proudly in the hopes of deterring Rowland’s damning fate. The struggle that followed between the pitted races before the city’s courthouse proved decisive. With one misfired shot, the life of a White man was ended, and the future of Greenwood guaranteed. It would burn; and so, it did.

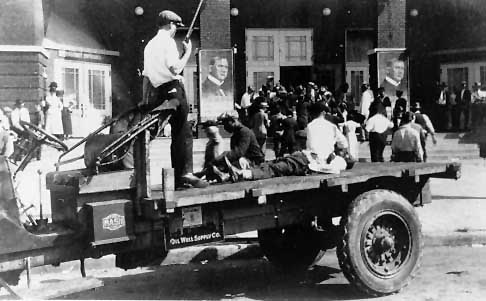

Driven by the belief of superiority and the indignation of having said status challenged, hundreds of Whites, claiming to have been commissioned and armed by the Tulsa police department, ravaged the African-American district, intent on destroying a community that had so impressively overcome the status quo dictated by history.[15] In an almost unnerving shift, a populace of bankers, grocers, and doctors, transformed into murderers, looters, and arsonists, who un-mercifully eradicated in hours, that which had taken decades to create.

Daybreak did not afford any relief to the persecuted Greenwood residents. Instead, the prior night’s atrocities, which had left anywhere between thirty to three hundred African-Americans dead, were only exacerbated by the involvement of the Oklahoma National Guard. Arriving in the early hours of June 1, 1921 flanked by aerial presence, the force took upon themselves the systematic scouring of the destruction for survivors. Those found were immediately placed under arrest and shepherded to makeshift “concentration camps” located sporadically throughout the district.[16] When the riot finally abated, these same individuals, numbering in the thousands, would remain homeless and disparaged, steadfast in their refusal to leave behind the haunted landscape that held the ruins of Greenwood’s buildings and the souls of its murdered residents.

The need for re-construction was immediately realized. But, the support that was offered by the remaining Tulsa populace did not reflect the hopes of revival as imagined by the displaced African-Americans. Instead, assistance was readily available under the condition that the remaining community of Greenwood would willingly relocate, a premise that was blatantly refused by those afflicted. With disregard towards the proposed resolution given by the city, the once prosperous Blacks of Tulsa struggled through a series of ordinances that restricted and sabotaged any attempts made at keeping and building upon the land that had been shaped by their culture and ambitions.[17]

A series of failed lawsuits, appeals, and reparation committees characterize the riots legacy throughout the next decades, until its atrocities became legally recognized by the Tulsa Race Riot Commission of 1997, seventy-five years after the assault on Greenwood’s residents. The goals of said commission included the preparation of a more detailed and truthful history of events that occurred on March 31, 1921, as well as proposing a means of reparation for the survivors of the brutal attack.

The investigations of the almost century old crime, embarked upon by the commission’s appointed members, revealed strikingly varied interpretations of that nights occurrences. Some blacks believed the burning to have been a pre-meditated strike against the affluent neighborhood of Greenwood, while Whites claimed the riot to have been a to the abrasive resistance of the veterans who had stood their ground before the Tulsa jail house.

With some consideration of the competing narratives and unresolved perplexities of that night, including how many people actually perished, the Commission nonetheless opted for some form of reparations to those who had suffered at the hands of young Tulsa’s racist manifestations. But, once more, the deliverance of justice was resisted, this time by the Oklahoma state legislature, who deemed the riot to have been a result of historic circumstances, and therefore morally excusable.

The survivor’s testimonies, which had finally received its deserved audience after almost a century of denial and dismissal, eventually succeeded in swaying the mind of the legislative body in 2000, resulting in the passing of the “1921 Tulsa Race Riot Reconciliation Act.” Therein lay the admittance to the failed action of Oklahoma’s government, the considerable opposition to the re-constructing of Greenwood, and the ethically flawed mindset of White Tulsans. Absent in the content of the apology are the long-overdue reparations, still to be evidenced. Yet, more importantly, the true sorrow, consideration, and respect that the existing ghost of the Tulsa Race Riot deserves, remain seemingly forever un-met.[18]

[1] Burt, Elizabeth V. The Progressive Era: Primary Documents on Events from 1890 to

1914. (Greenwood Publishing Group, 2004) 1.

[2] Butler, John. Entrepreneurship and Self-Help Among African-Americans: A

Reconsideration of Race and Economics. (SUNY Press, 2005) 216.

[3] Rucker, Walter, & Upton, James. Encyclopedia of American Race Riots. (Greenwood

Publishing Group, 2007) 252-253.

[4] Term coined by Booker T. Washington on his initial visit to Greenwod in 1918.

Perkins, Darren,J. Business is War: The Unfinished Business of Black America.

[5] Hirsch, James. Riot and Remembrance: America’s Worst Race Riot and Its Legacy.

(Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2003) 30.

[6] Wang, John, & Olson, Nadine. A Journey to Unlearn and Learn in Multicultural

Education. (Peter Lang, 2009) 59.

[7] Hirsch, James. Riot and Remembrance: America’s Worst Race Riot and Its Legacy.

(Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2003) 83.

[8] Information provided by Hannibal B. Johnson and taken from the source

http://www.hannibalbjohnson.com/Articles/tabid/64/articleType/ArticleVi

ew/articleId/9/The-Ghosts-of-Greenwood-Past-A-Walk-Down-Black-Wall-

Street.aspx on January 11, 2011.

[9] Information provided by World’s Own Service by The Tulsa World from the source

http://www.tulsaworld.com/news/article.aspx?subjectid=13&articleid=010

118_Ne_a12mabel&archive=yes on January 12, 2011.

[10] Vaughn, Leroy. Black People and Their Place in History. (Lulu.com, 2007)166-168.

[11] Hirsch, James. Riot and Remembrance: America’s Worst Race Riot and Its Legacy.

(Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2003) 46.

[12] Ellsworth, Scott. Death in a Promised Land: The Tulsa Race Riot of 1921. (LSU Press, 1992) 47-48.

[13] http://www.houseofnubian.com/IBS/SimpleCat/product/ASP/product-id/870465.html

[14] Information, written by Scott Ellsworth and taken from

http://www.tulsareparations.org/TulsaRiot1Of3.htm on January 12, 2011.

[15] Barkan, Elazar, & Alexander Karn. Taking Wrongs Seriously: Apologies and

Reconciliation. (Stanford University Press, 2006) 245.

[16] Brown, Nikki, &Stentiford, Barry. The Jim Crow Encyclopedia: Greenwood

Milestones in African American History. (Greenwood Publishing Group,

2008) 791-793.

[17] Brophy, Alfred & Kennedy, Randall. Reconstructing the Dreamland: The Tulsa Riot

of 1921: Race, Reparations, and Reconciliation. (Oxford University Press,

2003) 93-96.

[18] Barkan, Elazar, & Alexander Karn. Taking Wrongs Seriously: Apologies and

Reconciliation. (Stanford University Press, 2006) 241-243.