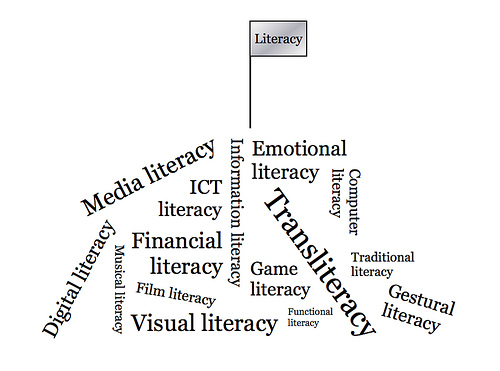

Types of Literacy Skills

There are various types of literacy and literacy skills. For instance, people have needed to increase their computer literacy over the last 25 years as computers have become common in daily life and work. Then, a person may require specialized literacy skills based on their occupation or interests, like an engineer or bird enthusiast. But these do not represent the essentials of literacy skills.

We must first know a basic definition of literacy: the ability to read, write, and understand words. Although this is a barebones explanation, there is more.

Literacy also entails important sub-skills that lend to deeper comprehension, like needs assessment, appropriateness, point of view, deciphering fact from opinion, knowledge organization and integration, and so on. Such critical thinking skills help to produce fluidity of knowledge and intellectual astuteness.

Yet the foundation of literacy skills rests solidly in reading development and acumen with the wide range of a language substructure.

Literacy has never achieved the rates witnessed around the world today. Scholars believe that rates in the Roman Empire were only about 10-15 percent and definitely not higher than 20 percent. Today most people know how to read and interpret facts decently well. Rates are very high in Westernized nations—highest in the Scandinavian countries—and significantly lower in parts of Africa and Asia.

Unfortunately, illiteracy persists for different reasons, from folks’ ability to hide their problem to—as we have seen in recent times—terrorist suppression.

How to Measure Literacy Skills

The National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL) delineates three types of literacy skills that demonstrate all reading is not the same. These types serve as a foundation to every other kind of literacy.

- Prose literacy. These are the skills needed to use continuous text, like news stories, editorials, brochures, and instruction guides. A reader should be able to search text for information and distinguish and comprehend concepts found therein.

- Document literacy. These are skills needed to use non-continuous text in various formats, like job applications, maps, payroll forms, and tables. The same applies here as with prose literacy, but today “various formats” may appear on a car GPS and on online job applications.

- Quantitative literacy. The skills needed to perform computations using numbers found in printed text. These tasks may include balancing a checkbook, completing an order form, or figuring a tip.

As you can see, these skills are foundational to working within other fields that may come with their own kind of literacy and nomenclature. Here lies a poignant reason why learning to read is crucially important: Learning begets learning. The more one knows, the more he can accomplish, meaning convert into work and a better socioeconomic condition for himself.

NAAL is the most comprehensive measure of adult literacy in America.

Interesting Literacy Stats:

- America's most literate cities are Washington D.C., Seattle, Minneapolis, Atlanta, and Boston

- Cuba has the highest overall literacy rates

- Most nations define literacy as being age 15 or more and can read and write

- Between 1994 and 2003, 47 percent of persons 16-65 years in Italy had functionally illiterate skills

- 85% of US juvenile inmates are functionally illiterate

- Ethiopia had a literacy rate of 28 percent in 2011

What is Functional Illiteracy?

This brings up an important aspect of the topic: functional illiteracy—inadequate literacy skills that prevent a person from managing personal or employment needs that require reading skills above a basic level.

Functional illiteracy is not illiteracy, describing a person that cannot understand basic words. A functionally illiterate person may read well and also comprehend, but their literacy level does not permit them to complete certain literacy requirements.

This becomes crucially important in daily life. A functionally illiterate person often cannot comprehend job advertisements, bank statements, and instructions for their own medications. In the U.S. 1 in 7 adults is functionally illiterate.

Further, functional illiteracy becomes an indicator—of poverty and possible crime. Forty-three percent of adults at the lowest literacy levels live below the poverty line. Sixty percent of inmates read at the 4th-grade level. Low literacy levels among poor, late-teen girls make them six times more likely to have out-of-wedlock children. So not only is literacy important for education purposes, it makes all the difference in one’s quality of life.

More programs for adult literacy are necessary, especially as society advances and daily life becomes more computer-based. More importantly, many of these adults—that you and I know—are being left behind in a game of advancing-society-catch up. Thinking outside the box might be for literacy programs to extend their approach by adding other computer and technology-based literacy emphases to their courses so that just-learned adults are better able to compete in society.