Controlling Rivers & Managing Watersheds

Humans have inadvertently messed up nature in many ways due, in large part, to the lack of knowledgeable land and water management. In Southern California we depleted what used to be an abundant supply of groundwater. In Southern Louisiana nature had a system to create new land that we blocked. These are not isolated cases - we've inadvertently messed up many of our nation's watersheds.

Although the decisions for how to function within different watersheds have been different, the principles and considerations of management are similar. To really get a feel for what a watershed is and how to manage it, we can compare actual situations - the Lower Mississippi River in Louisiana and the Arroyo Seco in Southern California.

The Lower Mississippi River Basin and the Arroyo Seco Watershed have been shaped in very different ways by the terrain and the economic needs of its settlers. Both have been strongly affected by the building of dams built for different purposes. The dams have worked in some ways, but in other ways they have hurt.

The Lower Mississippi is located at the bottom half of the mature Mississippi River watershed, including the Atchafalaya River, to which the Mississippi has been attempting to relocate as it flows to the sea. The Arroyo Seco watershed is at the beginning of the Los Angeles River near the foothills. In their natural state, both rivers are alluvial, in that they build land by carrying and dropping silt, frequently changing course in the process. Each watershed includes the very beginnings of the river all the way to its end.

What is a Watershed?

A watershed is the section of land from the mountains to a major water body (ocean or lake) toward which all water flows. Looking down from the air, the flow generally appears in a fan shape, where you can see rivulets from the mountains converging into streams at the beginning edge of the fan, which join into small rivers, then narrow to a single large river that flows to a lake or ocean.

The watershed includes the side of the mountains down which water flows, the whole valley beneath and between where water is generally stored, and the other end of the valley where water flows out, usually depositing debris as it goes. In other parts of the world, this area is called a "drainage basin." The ridges that separate drainage basins are called "drainage divides" - like the Continental Divide in the Rocky Mountains. Where one river flows into another river - like the Missouri River flows into the Mississippi - that area is called a "river basin."

A Look At The Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is one of the biggest river systems in the world. It has seven rivers that drain from part or all of 31 US states, plus two Canadian provinces. The entire river is estimated to be 2,530 miles long (4,070 km) from its beginnings to the end, where it drains out at the Gulf of Mexico. Baton Rouge and New Orleans are located near its outlet, southeast of the Atchafalaya River, which runs parallel to the Mississippi and is connected by a tributary known as Old River. Neither city would exist, had man not drastically altered nature's systems.

Here are some unique features of this area:

-

The Mississippi is the fourth longest river in the world. It has been trying to change course for the last several years at its southern end to merge with the Atchafalaya, which would leave the port city of New Orleans dry, with its river channels reduced to sluggish trickles.

-

The southern Mississippi River has become one of the most concentrated corporate locations in the United States. Those corporations - mainly oil and pesticides (Monsanto) - use the river between Baton Rouge and New Orleans for transportation of goods to the Gulf of Mexico.

-

It is the site of a long-term struggle between nature, and the local and federal governments that cater to corporate needs, with the government trying to control the flow of the mighty river using dams, sluices, and levees.

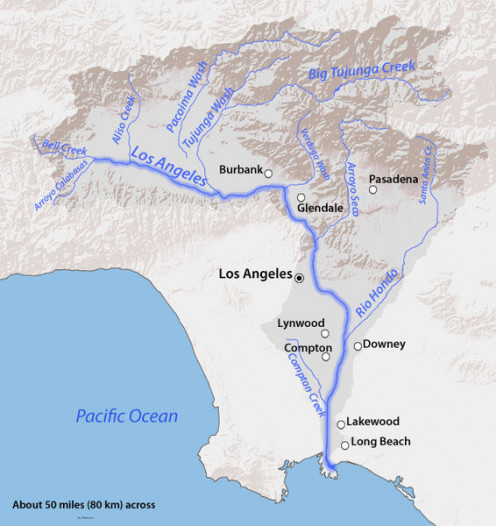

A Look At California's Arroyo Seco Watershed

Compared to the Mississippi, the Arroyo Seco Watershed is tiny. It starts at the foothills of the San Gabriel Mountains just north of the City of Pasadena in Southern California. It's one of several small watersheds that make up the Los Angeles River Basin, which covers a land area of 834 miles. The river is Los Angeles River is 48 miles long (77 km) in its entirety and drains west into the Pacific Ocean. Because of its strategic location at the edge of one of the biggest cities in the world (that once had major floods) the Arroyo Seco and it's neighboring watersheds are watched carefully.

Here are a number of interesting features about this tiny watershed:

-

Rainstorms feed the river in winter, but it dries up in summer.

-

The mountains that feed it are covered with chaparral, which burns hot in periodic wildfires that waterproof the soil, but which needs the fire in order to reproduce. However, waterproofed soil causes heavy flooding when it rains.

-

These mountains are the edge of the Pacific tectonic plate moving northward. Because of constant grinding pressure, the mountains are crumbly, hence rainstorms regularly wash down gravel, rocks, and boulders up to several tons in weight.

-

Pasadena and its neighboring cities have filled the valley and expanded into the foothills, where rock and mudslides are common and destructive.

Managing The Watersheds

Have these watersheds been managed well, or are humans causing more problems than they're solving? Most government activities are a combination of good and bad practices.

Bad management results when government officials or departments make decisions and approve permits without consulting those affected or considering the natural functions of the watershed. Very often they are just "doing their job." Sometimes they are accepting money or favors. Some officials don't know what they're doing, and some hide what they're doing. Seldom do they consider the long term effects of their decisions or the potential impact on neighboring communities.

"More than $450 billion in food and fiber, manufactured goods, and tourism depends on clean water and healthy watersheds." - U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

Good management is when all affected parties gather to develop an overall plan with guidelines for making decisions. The plan is reviewed and refined on a regular basis. Those responsible for carrying it out do so with integrity. The public and media keep watch and alert officials if anything goes wrong. There are no "sides," just groups of people with different interests and perspectives working together. Nature is put first, since Nature must necessarily thrive in order for humans to thrive. Let's look at how the Mississippi and Arroyo Seco watersheds have been managed.

- Water Topics | US EPA

Learn about EPA's work to protect and study national waters and supply systems. Subtopics include drinking water, water quality and monitoring, infrastructure and resilience.

Past Management of the Mississippi

Nature's way is for a river to flow the shortest way possible to reach its destination. As the river flows and slows, it drops sediment, which creates land. Eventually this new land may begin to block the river, which then changes course. In its new course it drops more sediment, creating more land, then changes course again.

For the last several decades the Mississippi River has been trying to change course to flow west through the Old River into the Atchafalaya River flowing south to the Gulf. But the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, at the behest of corporations located along the Mississippi, built $7,000,000,000 worth of dams, locks, sluices, and levees to stop it from changing.

Both cities and the corporations that feed them have become dependent on the Mississippi's current course and are reluctant to consider alternatives. As a result, while the government builds the levees higher, the Atchafalaya swamps are dying for lack of fresh water, the delta is washing out, and the land around New Orleans and Baton Rouge has sunk well below sea level. Floods and hurricanes are becoming more destructive as time goes on.

Not only is the land suffering, but the "protection" is causing devastating economic effects as well. The livelihoods of all people in the area not connected to the corporations are falling apart, along with the ecosystem. The dams, sluices, and dykes are costly to build and expensive to maintain. The river is losing its exit, the land is losing its soil, the people are losing their livelihoods, and the government is losing money. The only ones really winning are the corporations shipping out goods and businesses catering to the tourist trade.

Past Management of the Arroyo Seco

Management of this watershed focused on keeping residents safe. As fires raged in the hills, followed by heavy rain and rockslides, county officials built debris basins (a different kind of dam) all along the foothills and up into the canyons to prevent houses from being crushed and property washed away. The cuts into the hills, necessary to build the basins and roads to access them, loosened more rocks that washed down over time.

Although the basins did work for several years, they needed to be cleaned out as debris accumulated behind them, which cost taxpayers billions of dollars. If not cleaned out in time, the basins themselves overflowed or were crushed, while their accumulation of boulders and silt magnified the slides, making the destruction worse.

Unfortunately, this costly government protection gives residents the illusion that living in the canyons and foothills is safe. Real estate agents and developers whitewash the danger by telling home buyers that they, "Haven't seen any activity in awhile" or "Used to be problems, but the government took care of it." So the city continues to expand into unsafe areas, while the mountains continue their rising and crumbling, and universities continue the fascinating study of what happens where tectonic plates converge.

What do you think?

Must we control Nature in order to thrive?

Watershed Management Plan

We cannot thrive on an unhealthy earth. Historically, human expansion has involved leaving areas we have undermined and moving to areas that are still healthy.

Over time, however, humans are becoming aware that we've played a major role in ruining previously healthy ecosystems. Since we're running out of room now, it behooves us to start taking care of the land where we currently live. The best way to do that is to gather interested and knowledgeable parties together to create a master plan for development.

Because water is the one resource without which we cannot live in an area, putting hydrology at the center of such a plan is key. This is called a Watershed Management Plan. Let's see how these two watersheds are currently doing in this regard:

Lower Mississippi - Until recently, the primary planning body for the Mississippi River and Delta was the US Army Corps of Engineers. For a long time they were committed to keeping their structures in place to protect New Orleans. But since 1932 Louisiana has lost more than 2,000 square miles of land along it's southern coastline and much of what is left has drastically degraded. Nonprofit groups like Lower Mississippi Riverkeeper have been monitoring and reporting on these decreasing coastal conditions for the last several years.

Still Controlling Nature

Starting in 1978, the State of Louisiana took over watershed management. They passed several pieces of legislation limiting harmful development, and set up a Master Plan for coastal restoration. Instead of letting the Mississippi River just change course, which would restore the delta quickly but annihilate Baton Rouge and New Orleans, they decided to redirect water manually through channels that oil companies would dredge, aiming to restore the wetlands without causing devastating floods. If that doesn't work, they will consider closing the delta outlet and paying remuneration to whichever corporations have to relocate.

Arroyo Seco - For the Arroyo Seco Watershed as a whole, the overall planning body is the Los Angeles County Flood Control District, established in 1913 and now governed by the Public Works Department of Los Angeles County. The U.S. Forest Service manages the mountain side of the watershed, and each individual city manages their portion of the alluvial side of it.

The area's citizens have long been interested in preserving the beauty and functionality of the Arroyo Seco Canyon - the watershed's main drainage outlet - and in 2002 initiated several ongoing studies, which required collaboration between citizen groups and government. The agencies taking part in the studies included the US Army Corps of Engineers, City of Pasadena, US Forest Service, County of Los Angeles, and at least six nonprofits, led by the Arroyo Seco Foundation.

In 2003 Pasadena developed an Arroyo Seco Master Plan and Environmental Impact Report (EIR). Working in conjunction with the county and the public, the city also developed a master plan for a strategic portion of the watershed - the 1400-acre (6 km2) Hahamongna Watershed Park, located right up against the mountains at the beginning of the arroyo. Since citizens have insisted on being part of the planning process, plans for the watershed have become more of a collaborative effort than before.

Citizen Involvement is Key

Key to good management of any watershed is citizen involvement. Government officials have a particular outlook and vision, but don't experience the results as strongly as does the average citizen. In both of these cases - the Lower Mississippi and Upper Arroyo Seco - once citizens started pressing for action, they got changes.

When citizens become involved in concentrated numbers (e.g. nonprofits), speaking out in strong, but constructive ways, the government listens. Where citizens have been willing to help with research, the government has paid attention to it. In both locations above, citizens were the key to showing governing bodies the results of past actions and helping to develop new, more effective watershed management approaches.

- Economic Profile of the Lower Mississippi Region

PDF report prepared for the Economics Division of the US Department of Fish & Wildlife (158 pp). Covers economic benefits of natural resources harvesting, recreation, tourism, water supply, agriculture and more. - Welcome to the Arroyo Seco | Pasadena Dept. of Public Works

Affectionately known to locals as simply “the Arroyo”, the Arroyo Seco in Pasadena is protected parkland and open space with 22 miles of trails and myriad recreational opportunities. - Los Angeles County Watershed | LAC Flood Control District

A watershed is the land area where water collects and drains onto a lower level property or drains into a river, ocean or other body of water.