When Violent Civil Disobedience is Justified

Introduction

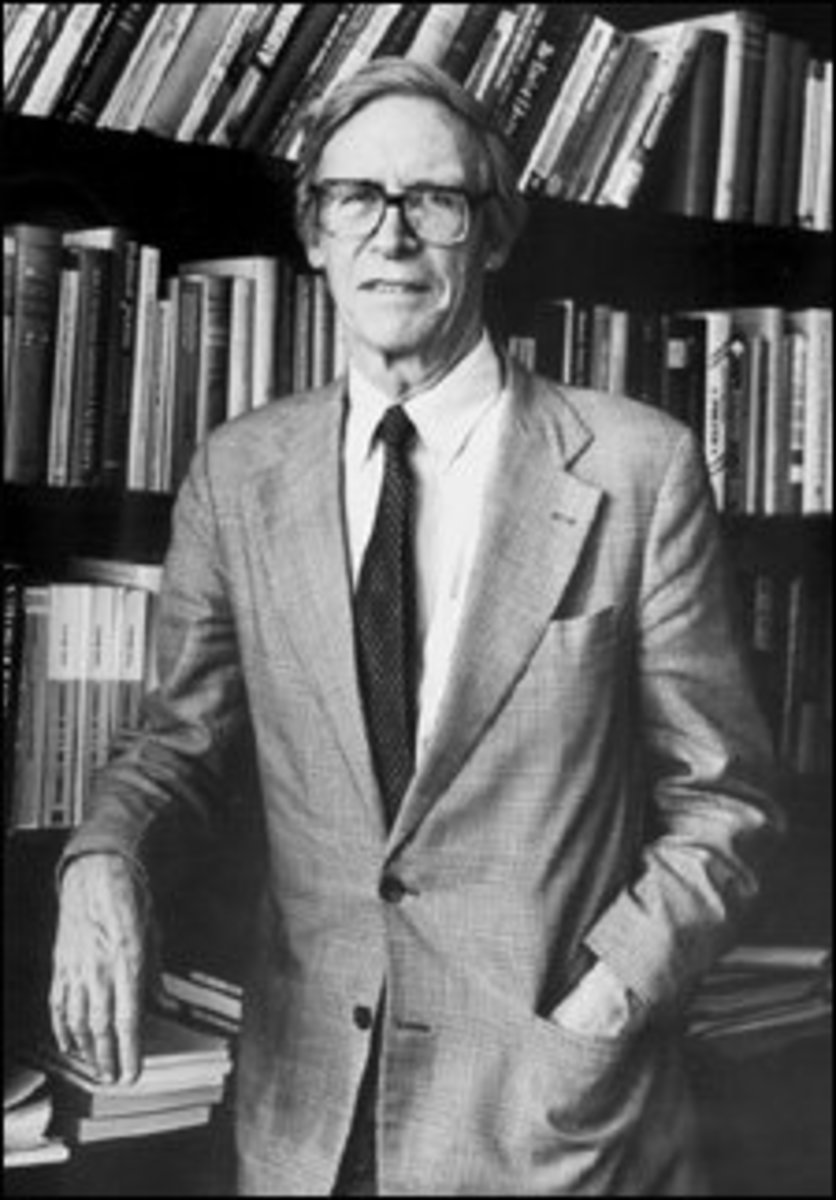

John Rawls, a philosopher, believes that civil disobedience cannot justly include violence; however, civil disobedience that resorts to violence can be justified under certain conditions. A combination of conditions is needed to justly use violence in civil disobedience. Firstly, the violence used would necessarily break the social contract; nonetheless, violence can justly be used if it is utilized to change a law that breaks the social contract itself. Secondly, violence must produce less harm than the law that civil disobedience is opposed to in order to be just. Thirdly, civil disobedience cannot justly produce violence unless such violence is used as a last resort. And, finally, violence is justified in civil disobedience because it allows the minority to have a voice when its rights are infringed upon. Rawls was too quick to dismiss violence because of its apparent contradictory nature to justice; still, one must acknowledge that, when the law of the land has a gaping wound of injustice, a little alcohol on the wound may sting temporarily but is helpful in preventing debilitating infections.

Condition 1: Fix the Social Contract

To prevent the perpetuation of injustice in a law that breaks the social contract, violence may be taken in civil disobedience. Still, Rawls argues violence cannot be allowed because civil disobedience “is intended to address the sense of justice in the majority” (Rawls, 1969). Rawls therefore believes that violence always skews one’s message of justice because of its inherently unjust nature. On the other hand, violence can awaken people to the extremity of injustice in society. If citizens protest particular laws vehemently through violence, then it follows that they either sense a great injustice from the laws or that they are violent for self-satisfaction and use the laws as an excuse. The latter reason is, of course, unjust because it is harming the basic rights of others for personal gain; however, the former reason is just.

Rawls would argue that it is unjust to use violence though because it breaks the social contract, which states that “we consent to certain principles to allow social arrangements to function” (Rawls, 1969). Nonetheless, this contract is broken by the government when it does not extend an equal liberty to the people, as Rawls puts it. If such is the case, and the social contract is broken by a law of the government that impedes equal liberty, it stands to reason that the citizens can justly protest the law through violence. This is because a contract requires obligations from two parties; if one party breaks the contract, the other party is not held responsible for the terms and conditions laid out in that contract. In fact, the other parties’ response of not fulfilling the contract is a measure taken to cause change in the one parties’ wrongful actions. As an illustration, imagine a boy who agrees to do his homework before he is allowed to watch television; if the boy breaches this agreement by watching television without doing his homework, then the parents would not be wrong in taking the television away. This action of taking the television away is a corrective measure to teach the boy not to shirk on responsibilities; surely anyone would not agree this action is unjust on the parents’ part. In response, Rawls would probably argue that civil disobedience with violence is similar to the parents reacting by hitting the boy for breaking the agreement, which brings me to my next condition.

Condition 2: To Reduce Overall Harm

Violence in civil disobedience is justifiable if it leads to overall less harm than the unjust law it protests. Civil disobedience functions to reduce the harm caused by the government and restore the citizen’s rights. If the social cost of harm caused by violent civil disobedience is less than social cost of harm caused by an unjust law, then – in a utilitarian sense – the overall level of harm is reduced and thus the violence used is just.

John Stuart Mill would disagree based on his harm principle that argues liberty should only be limited to prevent harm to others (Mill, 1869). Mill believes that harm to others is unjust because it infringes upon the rights of others in a society and therefore can be justly limited by the government. But, an overall smaller amount of harm caused from violent civil disobedience would be just because it would help create equal liberty.

Rawls believes that a principle of justice is that we all deserve an “equal right to the most extensive liberty compatible” with liberty for all (Rawls, 1969). More specifically, if citizens do not have equal liberty within reasonable limits, then the society in which they live is not just. Violent civil disobedience would help to attain this condition for justice by exerting pressure on unjust laws that harm equal liberty. If the liberty harmed through violence in civil disobedience is less than the liberty harmed through unjust laws, it follows that the civil disobedience is just because it promotes justice more than no civil disobedience would.

A counterargument Rawls may offer is that civil disobedience cannot promote justice through violence or at least would always promote justice more through nonviolence. Indeed, it would be ideal to not have to resort to violence in civil disobedience; yet, when nonviolent civil disobedience fails, violent actions may be the answer to achieve reform in unjust laws.

Condition 3: Last Resort

Violent civil disobedience can only be justified as a last resort, when nonviolent civil disobedience has failed to change unjust laws. Violence is not the best means of reforming unjust laws. As Rawls says, interfering with the basic rights of others “tends to obscure the civilly disobedient quality of one’s act” (Rawls, 1969). Violence certainly does interfere with the victims’ rights and thus may hurt the message of justice trying to be achieved through civil disobedience. On the other hand, violence may be the only means available to change a law. For example, if a kid is being beaten upon by five boys then it would be just for a child to step in and argue that the five boys should not beat up the kid. But, if the five boys do not cede to this request and beat them both up, then it would be just for the two boys to react by fighting back until they can run away to safety. The child who stepped in worked to maximize equal liberty by refraining from the breaking of others’ rights (not to be beaten upon); with no other more just means available, the child resorted to violence in order to achieve justice. Rawls may disagree by saying that the two kids would have only been just if they did not fight back. Nonetheless, fighting back helped the two kids to attain an overall less harm to equal liberty for all the kids involved by allowing them to escape; hence, it was the most just action available to them. Rawls may still reason that it would be better for civil disobedience to refrain from using violence even if violence offered a more immediate result. Still, Rawls fails to recognize that the minority may be powerless in changing laws, which hurt their liberty unjustly, without the use of violence.

Condition 4: Voice of the Minority

When a less powerful minority is opposed to an unjust law but cannot appeal to the majority to address its grievances, the minority may use violent civil disobedience justifiably instead of wait for the majority to act on the minority’s behalf. The minority should not wait until it gains a voice in political issues or until the majority surrenders to its demands because all the while the minority suffers from an unjust law. When the minority uses violence in civil disobedience, it likewise gains a voice in political issues. But, without violence, when the minority has no strong access to political institutions or those who run them refuse it to the minority, unjust laws can easily run rampantly against the rights and liberty of the minority.

Unlike Rawls may so believe, waiting through docile civil disobedience will not solve the problem of these unjust laws. Action is required in order for the ignored minority to make its demands reached. Violence is the solution in order to receive an immediate response to unjust laws; violence adds a threat that may seem unjust, but in actuality, it liberates the minority from unfair social conditions. It would not be just for the citizens to wait until the day comes, when the minority is trampled and beaten so severely by unjust laws, that the majority finally decides to cede equal liberty to the minority. Justice is equal liberty; thus, the lack of action for obtaining equal liberty is unjust.

Conclusion

Civil disobedience can justifiably contain violence if nonviolent civil disobedience has already failed in bringing into fruition the changes in an unjust law, which breaks the social contract; such changes in law must also be desired by a disgruntled minority and would only be just if the violence used leads to overall less harm than nonviolence would. An unjust law always certainly breaks the social contract because it denies the citizens equal liberty. This allows for citizens to engage in the breaking of the social contract in order to reform that unjust law. However, the citizens must limit the harm they bring to others in order not to exceed the harm done by the unjust laws. Also, this harm can only be brought about as a last resort, when nonviolent civil disobedience has failed because nonviolence would be the most just method available. Nonetheless, nonviolence may not work because the minority, that unjust laws destroy the liberty of, may be largely ignored by political institutions. The minority may thus use violence to gain a strong voice in political matters. As a result of all these conditions, in order to attain justice and minimize injustices, violence may be justly used in civil disobedience.

Sources

Mill, J. S. (1869). On liberty. London: Longman, Roberts, & Green

Rawls, J. (1996). The justification of civil disobedience. In F. Schauer & W. Sinnott-Armstrong (Ed.), The philosophy of law: Classic and contemporary readings with commentary (pp. 259-266). New York, New York: Oxford University Press.