Is Paraffin Young to Blame for Alberta's Oil Sands Pollution?

James 'Paraffin' Young

There are some who lay the blame at the feet of a long-dead Scots chemist, James ‘Paraffin’ Young. (Paraffin or Mineral Oil is known as Kerosene in North America).

Doctor Young 1811-1883 patented his method of distilling, or retorting oil from shale in the latter part of the 20th century in both Britain and North America. Those patents laid the foundation for the extraction of oil from shale or tar sands. But back in the 1860’s, pollution as we know it was unheard of.

Rather than being blamed, Paraffin Young should be lauded for bringing thousands of jobs to Fort McMurray and originating a vast industry that supplies oil to the world, duplicating the success of his original oil refinery which began distilling oil from cannel coal in Bathgate, West Lothian, Scotland. After his experiment with cannel coal, Dr. Young began retorting oil from shale, beginning an industry that lasted for 100 years.

Here I should admit that I will defend James Young to the death - even if he did inadvertently kill my Granddad. Paraffin Young is my hero, not just because I wouldn’t be if it wasn’t for him, but also because of his inventiveness and benevolence. At one point, Young’s Paraffin Light & Mineral Oil Company employed 10,000 people. Ten thousand people not counting spouses and children. His ideas transformed West Lothian into a power house of industry and altered the future of central Scotland

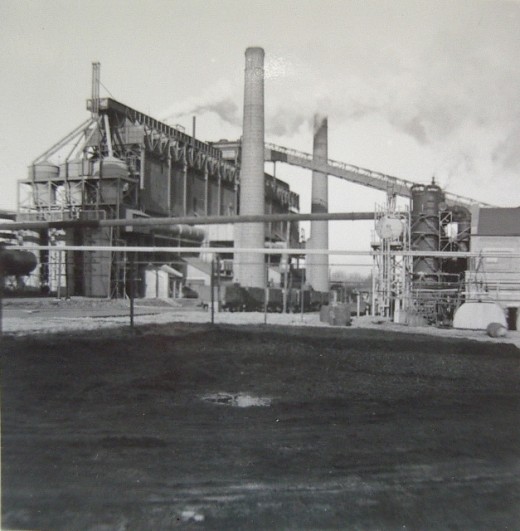

Reams have been written about how Dr Young patented his system of ‘cooking’ the shale in retorts and began an industry that lasted from 1862 until 1962. How, from the grey, flattish, sedimentary shale rocks, (they were great as skimmers) the company, eventually named Scottish Oils, mined over 3 million tons of shale per year at its peak, exporting lamp oil, paraffin, naphthalene, lubricating oil, grease and sulphate of ammonia – (a fertilising agent.) For a number of years, Scotland led the world in the production of oil and naphtha, and its ‘light oil’ was world renowned, as were Dr. Young’s patented oil lamps. (Actually they were Davy lamps, invented by Humphrey Davy from England)

The shale was so rich in oil to begin with, that it produced 40 gallons per ton, but over the decades, as the good stuff was used up, the poorer quality shale, which by then had to be mined from deeper and deeper pits, produced less oil per ton; eventually producing only 16 gallons of crude oil per ton. This didn’t matter during the Second World War, as the country was desperate for oil; in fact the government reduced the excise duty for every gallon the company produced.

In the late 1950’s, the company faced closure due to the importation of cheap oil (there’s an oxymoron for you!) from Iran. Over the next few years Scottish Oils was taken over by British Petroleum (BP) and made a valiant attempt to survive; not only did it produce the world’s first liquid detergent, ‘By-Prox,’ but it increased throughput by building a new experimental retort. The new retort, from an updated American design was successful, inasmuch as each ton of shale began producing 22 gallons of oil, but it was too late. The Westminster government revoked the subsidy, making the company unprofitable.

At one point there were over 100 shale pits operating in the 150 square kilometres that delineated the shale fields. Much like Alberta draws in immigrants now, so it was for the Scottish shale oil industry. It didn’t just siphon workers from other parts of the country, but brought in immigrants from Europe, mainly Poland and Ireland. I can vouch for the Irish part, as my maternal grandfather emigrated from Eire to Scotland during the 1870’s - the third Irish potato famine. First of all, he tried Canada (the first mention of Canada in the family) but didn’t stay long before settling in Scotland.

The P.L. & M.O. solved the problem of where to put all these workers by building villages for them – complete villages dedicated to one particular mine or work.

My Grandfather, who was a shale miner with Young’s Paraffin Light and Mineral Oil Co, was killed by a roof fall in Dean’s shale pit in 1927. He lived in the village of Deans, where my Father was born in 1897. My Mother, who also worked in the blacksmith’s shop at the pit, was born in 1900 in the P.L. & M. Oil Company village of Happyland. My wife was born in the company village of Roman Camp, – which was situated near a real Roman Camp to the North East of Pumpherston. I was born in Livingston Station, before the family moved to Mossend, another company village of around 200 homes. I guess sticking up for Paraffin Young must be in my genes.

Even in the 1940’s, which is the earliest I can remember, the rows of houses were basic, but they provided shelter, a place to start a family – in our case that would be my two older sisters and I. We had a single electric light in each room, but no plug points. There was a toilet (shunky) but no bath – the ‘bath’ was zinc and hung up outside in the garden until it was bath time. That meant every day for our father, who came home after a hard days graft, exhausted and sometimes unrecognizable under the dirt. The bath would be brought in, placed in the middle of the floor, and filled up with water heated in pots and pans on the range. The scullery had a single cold water tap.

There was no such thing as central heating or double glazing. There was a single fireplace in the living room. In winter we went to bed with our day clothes on top of the bedclothes in an attempt to keep warm (in the 1940’s the winters were pretty cold in central Scotland, a lot colder than they are now). We also used to place the bed’s legs in small basins full of water and pour naphtha onto the water until it formed a skin across the surface. This prevented the silverfish that carpeted the floor every night, from taking over completely, and we made sure to take our boots to bed with us.

Most of the villages were razed after the pits closed down, such as Gavieside; Livingston Station; Mossend ; Happyland ; and Limefield . There are still villages with the original names, but with no, or few, Young’s homes, such as Addiewell, Breich, Blackburn, Burngrange, Harburn, Brandy Braes, Hermand, Cobbinshaw, Seafield, Uphall and Broxburn.

* * *

Because of the nature of the shale seams, shale mining was inherently safer than coal mining as there was less chance of firedamp (methane), but it was more unstable than coal, leading to more cave-ins. And, because there wasn’t the same amount of dust in a shale mine as in a coal mine, the coal miners had a vastly greater chance of contracting pneumoconiosis. Because of this, coal miners looked down on shale miners, not that it bothered the shale miners, who were allowed the luxury of smoking at the bottom of the pit shaft.

What isn’t written about is Young’s P.L & M. Oil Co, most precious world wide export – people - skilled people, geologists, miners, blacksmiths, electricians, engineers, and chemists who emigrated around the world. The shale companies had a lot to do with boosting the respect in which Scots are held around the planet. Come to think of it, perhaps the shale oil industry also had a lot to do with how we got our reputation for parsimony – after all, we were squeezing money out of rocks.

* * *

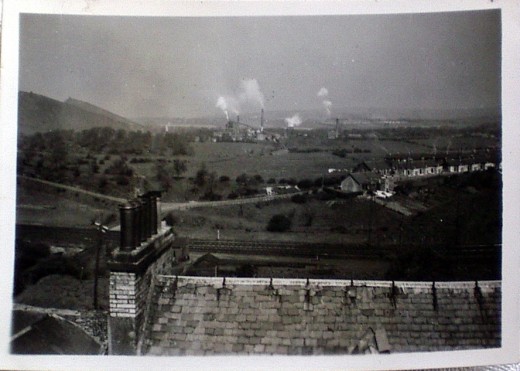

When I started working for the company in the 1950’s there were only three pits in the immediate neighbourhood – Westwood, Breich and Hermand. Addiewell was still working as a pit, but the shale was being sent to Westwood Works for processing. The pollution caused by these pits was outside any modern frame of reference.

The rivers didn’t quite run red; they were black and yellow instead. Falling into the black burn meant burning your clothes as attempting to clean them was a waste of energy. Falling into the yellow burn solved the cleaning problem; it dissolved your clothing as you wore it. The problem with the yellow burn was trying to get out of your clothing before your flesh was eaten away. The confluence of both burns was a no-go area. Nothing lived there, not even weeds.

The bings (from the Old Norse ‘bingr,’ meaning pile or heap of waste) were everywhere. Not just the reddish bings of spent shale that people nowadays associate with West Lothian, but small, black bings from a century of pits and works. Waste heaps so old that heather and whin bushes were growing on them, and residents accepted them as a part of the natural topography, not realising what they were. If the bing consisted of greyish/black shale instead of reddish shale, it meant that the shale hadn’t been retorted properly. There was still a large amount of oil locked up in that bing.

This created the ideal environment for spontaneous combustion. In one particular bing from the old Gavieside works, near Polbeth, the bing flared up suddenly. The local story was that a cow had wandered on to the top of the bing which had been quietly smouldering under the surface. The poor bovine’s weight caused it to break through the crust, and it became instant roast beef; at the same time allowing oxygen to flow in, hence the burst of flames. I can’t vouch for the story but I do know the bing had flames, smoke and fumes pouring out of it for years. Altogether it burned for 20 years, and other waste heaps burned for years

One bing, the Five Sisters, still dominates the landscape near West Calder, and it has now been incorporated into West Lothian's coat of arms. Why the Five Sisters? No reason at all; they were the beginnings of a monster bing like Addiewell’s. If the company hadn’t failed, after those five arms were finished, the spaces in between would be filled up and it would look like a normal bing after the hoppers tipped their loads along the top. The Five Sisters was only two sisters when I started working for Scottish Oils.

The ironic thing about the pollution was that many villagers who had emphysema or asthma or other breathing difficulties seemed to be cured if they were downwind of the smoke and fumes from Westwood Works. Now if Paraffin Young could have bottled that, he would be everybody’s personal hero.

After WWII, we moved from Mossend, to Polbeth, a council village – the houses we moved to in Polbeth were colloquially known as the Swedish Timber houses; Ikea’s first tentative export perhaps? This was next door to James Young’s original home, Limefield House and where his niece, Miss Thom lived in my day. My pals and I used to play along Limefield Burn. The burn was clean and just out of sight of Limefield House it had a waterfall, where we used to dare each other to walk along the top, or climb up the beech tree trunk that had been washed over in a spate and was wedged between the burn bed and the top of the waterfall.

It wasn’t until later that I discovered that Dr. Young had commissioned Limefield Falls as a tribute to his great friend Doctor Livingstone who had discovered Victoria Falls. There was slight discrepancy in sizes. Limefield wasn’t exactly the Zambezi River, and the waterfall wasn’t one mile across like Victoria Falls but apparently Dr. Livingstone loved it when he came to visit.

Before immigrating to Canada, we were privileged to stay for a few days in Limefield House, which had been turned into a guest house. We found it very fitting that we should both have come into this Scottish world in a Scottish Oils house and before leaving, stay in James ‘Paraffin’ Young’s own residence.

* * *

West Lothian has recovered from 100 years of rape, thank you for asking. The rivers and burns run crystal clear and the monster bings have been levelled. Any bings that do remain have been allowed to do so and are being used as wildlife sanctuaries.

And today, whether Paraffin Young or any of his ex Scottish Oils tradesmen or their descendants are to blame for the Alberta's Oil. You can be sure that Mother Earth will clean up after her thoughtless, short-term, looting tenants. Canada will recover from our pillaging.

Copyright 2015

N.B. Doctor Abraham Gesner

According to the book, ‘Canada Firsts’ written by Ralph Nader, Nadia Milleron and Duff Conacher, Doctor Abraham Gesner was the ‘father of night-life.’

‘Gesner may be called the forefather of today’s multi-billion petrochemical industry. However he did not benefit financially……A Scottish chemist, James Young, had developed a similar fuel in England and obtained a British patent for… “parafinne-oil” in 1850. Young’s patent preceded Gesner’s work…and Gesner had to pay royalties to James Young.’

Sounds like the work of a canny Scot.