Immigration: Why Don't They Just Learn English?: Why Language Learning is Harder Than You Think

"Everything That's Posted Here, I Should Understand"

"Why don't they just learn English?"

Many English-speaking Americans feel frustrated with immigrants who seem to require signs in their own language and/or interpreters in government offices, schools, doctors' offices and so on. A particularly extreme example of this attitude is the song Press One for English, by Rivoli Revue, found here. The singer expects not only that she should have services available to her in English, but that she not be expected even to look at other languages: "Everything that's posted here, I should understand." The music video includes old-fashioned photographs of various immigrant groups in English classes. The implication being, "Immigrants used to learn English, why can't they today?"

The Experience of Being A Foreigner

I am sometimes amused, sometimes bothered by this attitude because of my own experience of living as a foreigner. Several years ago, my husband and I moved to another country with the goal of living and working there for several years. Unlike many overseas workers, we were privileged to be able to spend our entire first year in the country doing nothing but learning language at a special school for foreigners. This is already an easier lot than that faced by many immigrants to the United States. For an entire year we did not have to get a job. Our only job was to be language students. We were enthusiastic and excited to begin learning the language and culture.

Nevertheless, there was still much that had to be done in our early weeks in the country. We had to find a house to stay in and negotiate the rental contract. We had to figure out where to shop for food. We also had to buy furniture, linens, etc. for our unfinished house. Each of these trips to an unfamiliar store, on a budget, in a climate that we were not yet used to, lasted hours and left us exhausted at the end of it.

But there were more important, and more linguistically demanding, tasks that we also had to accomplish. We had to report to immigration, to our local mayor, and to the police. We had to show up, in person, at any number of government offices, bearing the right paperwork (which was not always clear in advance what it would be), and then came the endurance test of standing in lines, sitting in reception rooms, and trying to explain in our broken language what we were doing there. Are we being soaked or is this a normal processing fee? We had no idea. But, we wanted to do everything legally. For some things we did, we were told that we should have done X or Y several days ago.

Left to our own devices, we could not have gotten even a fraction of our settling-in tasks accomplished. But we were lucky. We had lots and lots of help. Other foreigners who had been there before us walked us through the process of house hunting, and interpreted with our landlord. They showed us how to ride on local transportation. They took us to grocery stores. There were also English-speaking natives of that country who had been hired by our company to accompany us to the various government offices, advise us, interpret, and keep us from accidentally offending someone or breaking a law. These people were saviors, saints.

Nor were we in a country where Americans faced hostility. The average person's reaction to an American was basically positive.

Despite all these advantages; despite, in fact, having almost the easiest possible landing that a person can have in a foreign country, we still found those early weeks and months exhausting, frustrating, and difficult. We felt we were always screwing up. Our energy was never at 100%. We complained a lot. We were not our best selves, believe you me.

We did eventually learn the language. Made pretty good progress on it, actually. But there was no way we would have been able to learn it fast enough to navigate those early months on our own.

Have you ever lived in a country other than your own?

It Just Takes Time

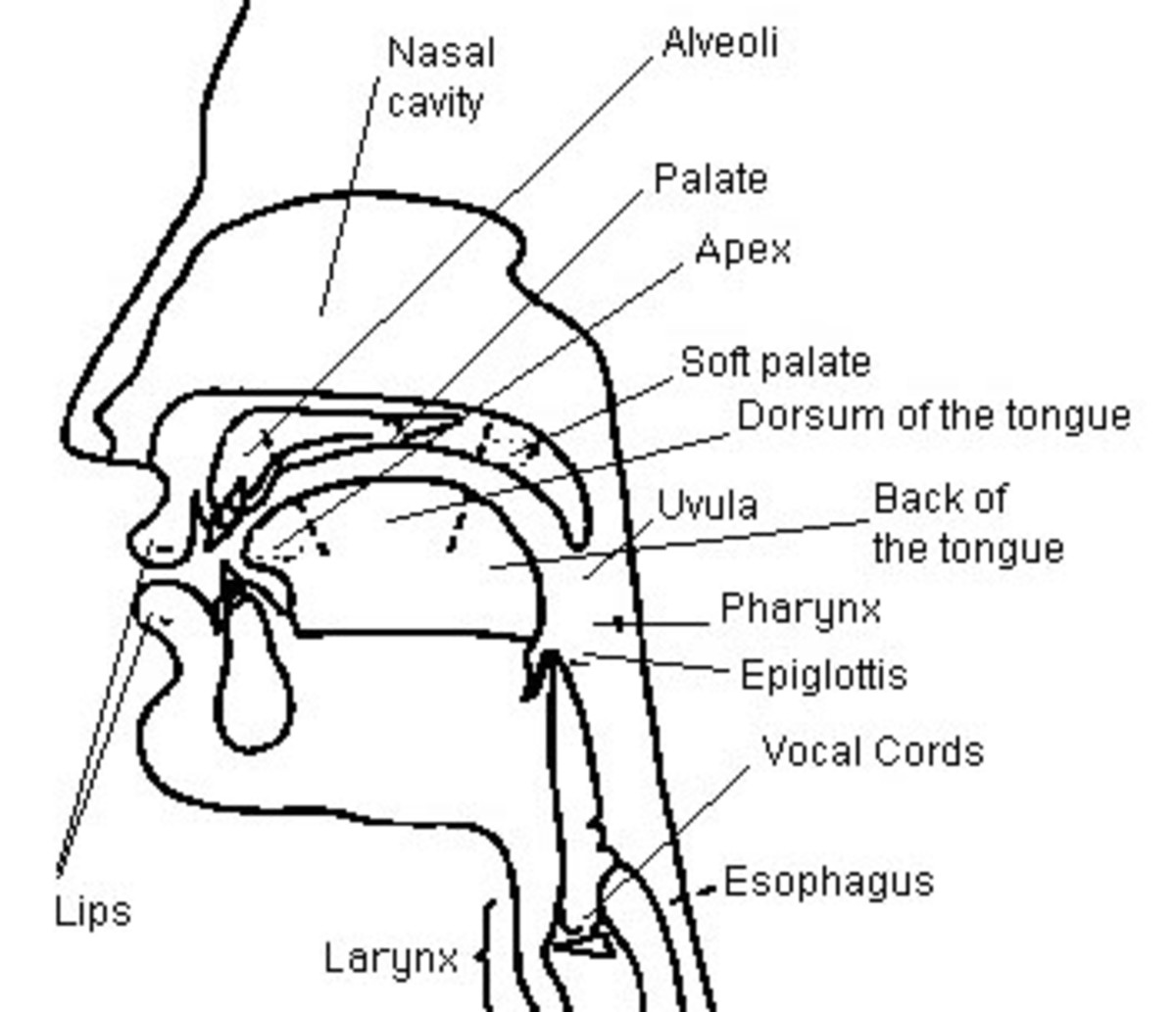

Language learning is harder, and takes longer, than many people realize. The U.S. Foreign Service Institute has come up with an estimate of how many hours of classroom instruction it takes the average English-speaking person to learn any number of world languages. The number varies from language to language. Some languages are harder for English speakers to learn because they differ greatly from English in their phonetics, phonology, or grammar. For example, Mandarin and Cantonese have tones.

The difficulty levels are not symmetrical. That is, a speaker of a language that is "difficult" to an English speaker might not find it as difficult to learn English. Or a speaker of an "easy" language might find learning English very hard. Or not. It just depends on the details of the two languages.

The FSI's full difficulty ranking can be found here. To take just a few tidbits, the easiest category of languages, which includes Afrikaans, Dutch, French, Italian, and Spanish, require roughly 575 to 600 hours to learn. This is to reach "minimum professional proficiency." That is, the person will be able to speak the language at a basic level that is adequate for most everyday conversations. They will not speak it "like a native."

The largest group of languages is found in Category IV, languages which take approximately 1100 hours of instruction time to master. Japanese, Cantonese, Mandarin, and Arabic are in Category V, which takes approximately 2200 hours.

The language my husband and I studied was in Category III (900 hours). After a year of studying four hours a day, plus socializing in the language during the rest of the day, we had reached the FSI level of "minimum professional proficiency" ... but just barely.

We were young at the time. If we had to undertake the same study as older people, our progress would probably be much slower.

Give 'Em A Minute - Or A Year

The conclusion I am heading toward should be fairly obvious here. "Learning English" is not a one-time event that can be done on a bus, on a plane, or standing in line at customs. It is a challenging mental task can take months of intensive study just to get a good start on it. For those who do not have the luxury of setting aside time exclusively for language study, it will of course take longer.

People who move to a new country are usually at a low ebb physically and mentally. They are exhausted from travel, disoriented by how they can't find anything, and worried by the many new tasks facing them. They may also be sick (fairly common on arriving in a new place). They have come from a land in which they were competent, functioning adults, to a place where they cannot do the most basic things without having someone walk them through it like a child.

Unlike my husband and me, they may also have a whole raft of physical and mental torments that come from the situation they were fleeing, whether they were hoping to escape poverty; crime and corruption; or were displaced by war. They may be broken by what they have gone through. My heart goes out to such people ... and, actually, it also goes out to those who are not even broken, just professionals seeking a new opportunity. Because broken or not, international travel (especially with small children) can leave anyone, by the time they are going through customs, looking and feeling like something the cat dragged in.

It is a bit much to expect that people arrive speaking English, or that they master it in a few weeks or months of night classes. Also, as anyone who has tried their hand at language learning knows, it is not reasonable to be offended by the sound of an accent, or to assume that a person with broken English is "not trying." Adults who learn another language will always speak it with an accent.

Ergo, I am not offended by the sight of signs in multiple languages. Nor am I offended when a phone tree instructs me to "press one for English." (Except insofar as phone trees themselves are annoying!) I personally find it rather delightful to talk with someone who is not a native English speaker. Though every person is different, many foreigners I have met turn out to be amazingly frugal, hardworking, funny, and patient as I and they negotiate our conversational misunderstandings and seek to find common ground.

Nor do I think that having signs and public services in multiple languages is a sign that America is losing its identity. Like the saviors/saints who helped my husband and me, these signs and interpreters actually make it easier for motivated foreigners to settle in, integrate, and do the hard work of language learning.

For more information, see Lucy Tse's book Why Don't They Just Learn English?: Separating Fact from Fallacy in the U.S. Language Debate, summarized and reviewed in the Harvard Educational Review.