You can Buy Anything Cheaply in China except Freedom of Speech

"The free flow of information is crucial, because that's how we discover truth, that's how we learn what's really happening in our communities and our country and our world”

— Michelle Obama, First Lady

Introduction

The first lady Michelle Obama's inaugural visit to China in March last year, followed by the Charlie Hebdo massacre last month in Paris, are two events that remind us of the great importance to the civilized world of the right to freedom of speech.

Despite being declared last year to be the "world's largest economy", when it comes to freedom of speech, the People's Republic of China (PRC) has a very long way to go indeed when it comes to this fundamental human right -freedom of speech. The PRC is one of the most restrictively censored countries in the world. News media are carefully censored by the government, and access to many internet sites freely available in the rest of the world is blocked.

The PRC blocks many foreign news sites and social media services such as Facebook, Twitter and YouTube. Its army of censors routinely filters out information deemed offensive by the government and silences dissenting voices.

Given China's ancient feudal history, in which it played a key role for centuries as a hub of learning and scholarship (including the art of calligraphy), it's hard to reconcile this repressive China of today, with Imperial China, in which a written language was developed, and the scribes in the monasteries presided over a flowering of language, culture and recorded history. It's also hard to reconcile such an economically successful and innovative country, with the denial of fundamental human rights like freedom of speech. How can China present such a paradox?

How much do you know about freedom of speech in China?

view quiz statistics

Why's freedom of speech so important?

Freedom of speech (or expression) is such a deeply-rooted principle in modern Western liberal democracies that most of us in the West take it entirely for granted. Back as far as 1948, the right was enshrined in international law under Article 19 of the International Declaration of Human Rights. It's reflected in most constitutions or charters of rights of Western countries, and thus is also enshrined in domestic law.

Not everyone agrees what 'free speech' actually means, and what its limits are. The US Supreme Court has often struggled, in free speech cases under the US Constitution, to define what it does or doesn't apply to. The Supreme Court's held that it includes a number of things we wouldn't perhaps traditionally associate with the 'free speech' concept, notably:

- the right not to speak (specifically, not to salute the flag)

- to wear black armbands to protest a war

- to use certain offensive words and phrases to convey political messages

- to advertise commercial products and professional services

- to contribute money to political campaigns

The Pope recently suggested that free speech does not (or should not) include the right to cause religious offence.

Debates aside though, we in the West can scarcely imagine a world in which our right to speak, and the very content of what we say, can be controlled and censored. We can't conceive of a world in which we open our web browser, and are granted access to only a handful of internet sites (with the remainder being blocked behind huge firewalls). The idea of being thrown into prison for things we have said or written about the government, is unthinkable. Yet these things currently happen in the PRC on a not infrequent basis.

Free speech is seen [by China] as a luxury for countries that are not trying to coordinate a massive, diverse, and historically unruly country in order to rise out of extreme poverty and global marginalization

— Jennifer Carvalho

Does the PRC protect 'freedom of speech'?

Generally speaking, Communist countries like China base their paradigm of society on the needs, rights and aspirations of the collective or community, not those of the individual. This makes a crucial difference when it comes to determining the values that underpin Communist societies.

Freedom of speech, like other human rights, is primarily a right vested in the individual. In a society where the community or collective interest is paramount, freedom of the individual to speak (or do anything else for that matter) is likely to be regarded as less important than the rights of the community at large, and of the political institutions. This will be especially so where an individual's freedom of speech comes into direct conflict with authority or the community (such as where the individual organises a protest or speaks out against the political masters).

As one might expect, this 'qualified' type of freedom of speech is exactly what's reflected in the Chinese constitution -which gives people the right of free speech, but then limits that right by things like not overthrowing the socialist system or advocating secession. Let's look at some specific examples:

Media censorship: The Chinese government has for a long time censored both traditional media and the internet to avoid potential subversion of its authority. Only news outlets deemed favourable to the government are allowed to broadcast on TV or radio. China blocks many foreign news sites and social media services such as Facebook, Twitter and YouTube. Its many censors work to filter out information deemed offensive by the government and silences dissenting voices. This censorship is often justified on grounds of 'protecting state secrets', or other vague security grounds. The watchdog group Reporters without Borders ranked China 173 out of 179 countries in its 2013 worldwide index of press freedom.

Imprisonment, harassment and surveillance of journalists. It's not uncommon for journalists or writers who write anything deemed negative or critical of the government to be imprisoned or placed under house arrest. Even foreign journalists operating in China have been subjected to harassment and surveillance, and have had cameras confiscated. China requires foreign correspondents to obtain permission before reporting in the country and has used this as a way of preventing journalists from reporting on potentially sensitive topics like corruption.

Imprisonment of government critics. Many writers, artists, academics and ordinary citizens have been arrested and imprisoned for criticising the government, even though China's 1982 constitution purports to protect freedom of speech. These arrests are often justified on grounds of 'subverting state power' or 'disclosing state secrets'.

Quashing democracy protests. Who can forget the Tiananmen Square massacre of 1989 in Beijing? This was a series of pro-democracy student-led protests, supporting by the city's residents, that were subject to a brutal crackdown by the Chinese authorities, and imposition of martial law, enforced by the army. Newsreels from that time show tanks rolling in, and assauly rifles being aimed at unarmed protesters -killing many of them. It's telling that since 1989, the Chinese government has prevented any discussion of the crackdown publicly or in the media, or any commemorative or memorial events being held. Similar protests were held in Hong Kong in September last year, and like Tiananmen square, the Chinese authorities had little tolerance for the protests -after protesters breached a security barrier outside the electoral office, Chinese armed forces came in and forcibly removed them the following day.

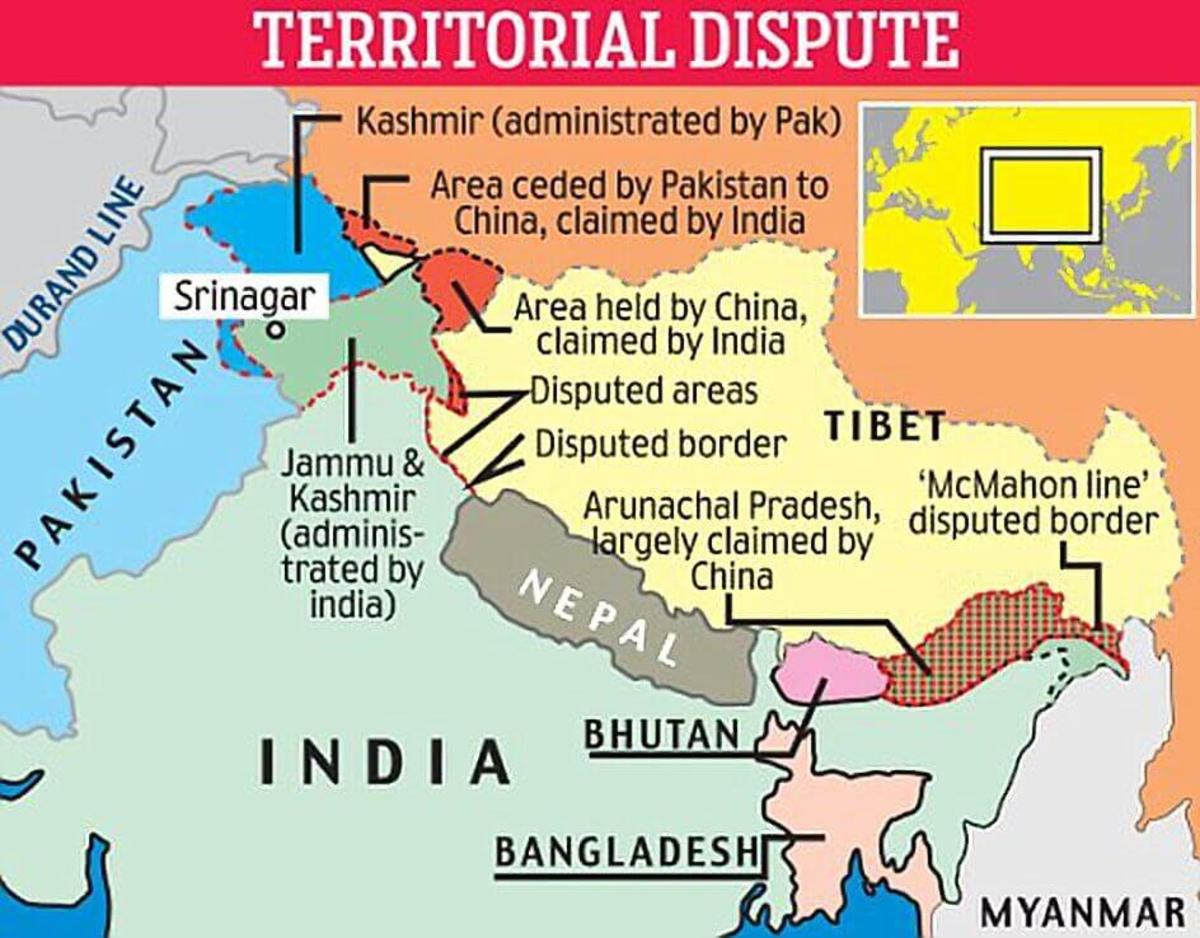

Religious freedom of expression. Another area where the PRC falls well short of international law requirements for protection of freedom of speech and religion. There have been many instances of persecution of religious sects (such as Tibetan Buddhists and the Falun Gong) by Chinese authorities, and arbitrary arrests and detention relating to religious practices (e.g. assembling for religious worship, expressing religious beliefs in public and in private, and publishing religious texts). The Chinese government has imposed restrictions on Islamic dress among its Uighur population, most recently by banning full-length burqas in Urumqi, Xinjiang’s capital city.

How important is freedom of speech?

How important is freedom of speech?

Tibet and China

Case Study: Tibet

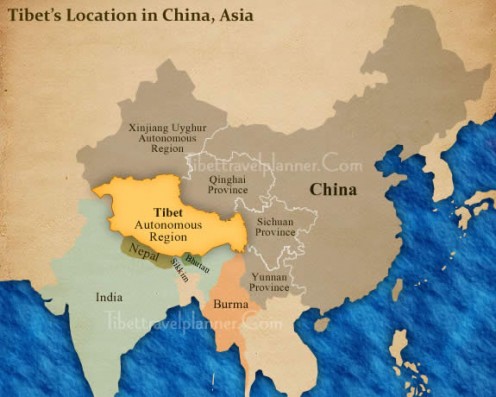

Tibet (since 1959 a territory of China) represents, perhaps more starkly than any other example in recent history, the failure of China's approach to free speech and democratic rights in its sovereign territories.

Formerly a proud feudal theocracy headed by the Dalai Lama (the high priest and leader of Tibetan Buddhism), in 1951 Tibet was invaded by China, many of its monasteries were set on fire or demolished, and monks and ordinary citizens alike were forced to denounce the Dalai Lama, and openly express their devotion and support for the Chinese communist government. In exchange for this, Tibet (a country based for centuries on subsistence agriculture), was promised a new wave of wealth and economic development.

Although life for the ordinary Tibetan may have become easier economically since its annexation by China, arguably Tibet has suffered a progressive form of cultural annihilation at the hands of China -with its language, religion and cultural practices at risk of being wiped out entirely. Nomadic populations of yak herders have been forced to resettle in permanent dwellings.

Most of all perhaps, freedom of speech has suffered in Tibet -both the freedom to speak the Tibetan language and to freely express religious and cultural beliefs, but also the freedom to criticise or question any measures taken by the Chinese government, which is omnipresent everywhere in Tibet (and is usually heavily armed).

Human rights abuses documented in Tibet include the deprivation of life, disappearances, torture, poor prison conditions, arbitrary arrest and detention, denial of fair public trial, denial of freedom of speech and of press and Internet freedoms. They also include political and religious repression, forced abortions, sterilisation, and even infanticide. The Chinese security forces have used torture and degrading treatment in dealing with some detainees and prisoners, according to the U.S. State Department's 2009 report. It's difficult to verify some of these claims because of media bans.

Sadly in Tibet, since the wave of street protests in 2008 was put down, Tibetan monks, nuns and ordinary citizens have resorted in increasing numbers to the extreme of self-immolation (suicide by fire), as a means of protesting what they see as an intolerable level of oppression in their own country. It is to be hoped that Chinese authorities take heed of this misery, and try to find a new approach to governing Tibet.

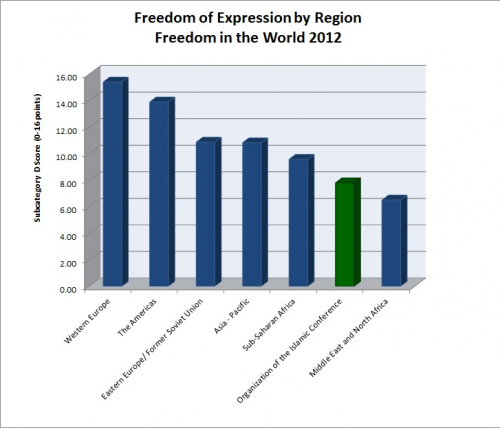

Freedom of expression -global regional index

Case Study 2: Uighur

China is practising similarly repressive policies toward the Muslim minority Uighur population in the Xinjiang province, as it practises in Tibet. Officials in Xinjiang have placed the Chinese flag inside mosques throughout the region, and have restricted many faithful (including children under the age of 18) from entering mosques at all. The Chinese government has also clamped down on bilingual education in the region, placing Uighur people (and for the Uighur, Mandarin is not a first language).

The PRC's policies in Xinjiang are driven by economics -the need to take advantage of the vast energy resources in that state, and to develop relationships with neighbouring countries to the West.

Like the Tibetans, desperation has driven the Uighur people to extreme measures -various terrorist groups have recently begun to operate in Xinjiang, with money and support from militants in Pakistan and Afghanistan.

Is there hope for free speech in China?

Unfortunately, at the present time, the political climate in the PRC doesn't favour greater moves toward freedom of speech in that country.

A few weeks ago, after the Charlie Hebdo massacre in Paris, officially-sanctioned Chinese media used that incident to reinforce the traditional view:

“The world is diverse and there should be limits on press freedom,” read the editorial by Paris bureau chief Ying Qiang. “Unfettered and unprincipled satire, humiliation, and free speech are not acceptable.”

For China, limits on freedom of speech are still considered to be entirely necessary in order to protect China's legitimate security interests -to prevent another 'Chinese 9/11' (the multiple stabbling on a train in the Yunnan province by alleged terrorists affiliated with Syria), and to promote order. It's difficult to see how (or why) China's views on this issue will change in the near future.