The Broken Window Effect: The Social Effects of Repairing Broken Windows

The Effect of One Broken Window

Newton's First Law of Motion

Every object in a state of uniform motion

tends to remain in that state of motion

unless an external force is applied to it.

Three Different Urban Areas

Before we get into the meat of things, I want to take a few moments so you can picture in your mind a few urban areas you've been to or seen pictures of, perhaps on the news.

There are three specific areas to picture. First, imagine the nicest neighbourhood you know. Think of the houses, street conditions, vehicles, people walking around, and stores, if any. Then, the downtown area in the largest city nearby and, finally, what an area full of crack flophouses looks like.

How did these three locations differ? How did they look the same? Were there any similarities?

Broken Windows Theory

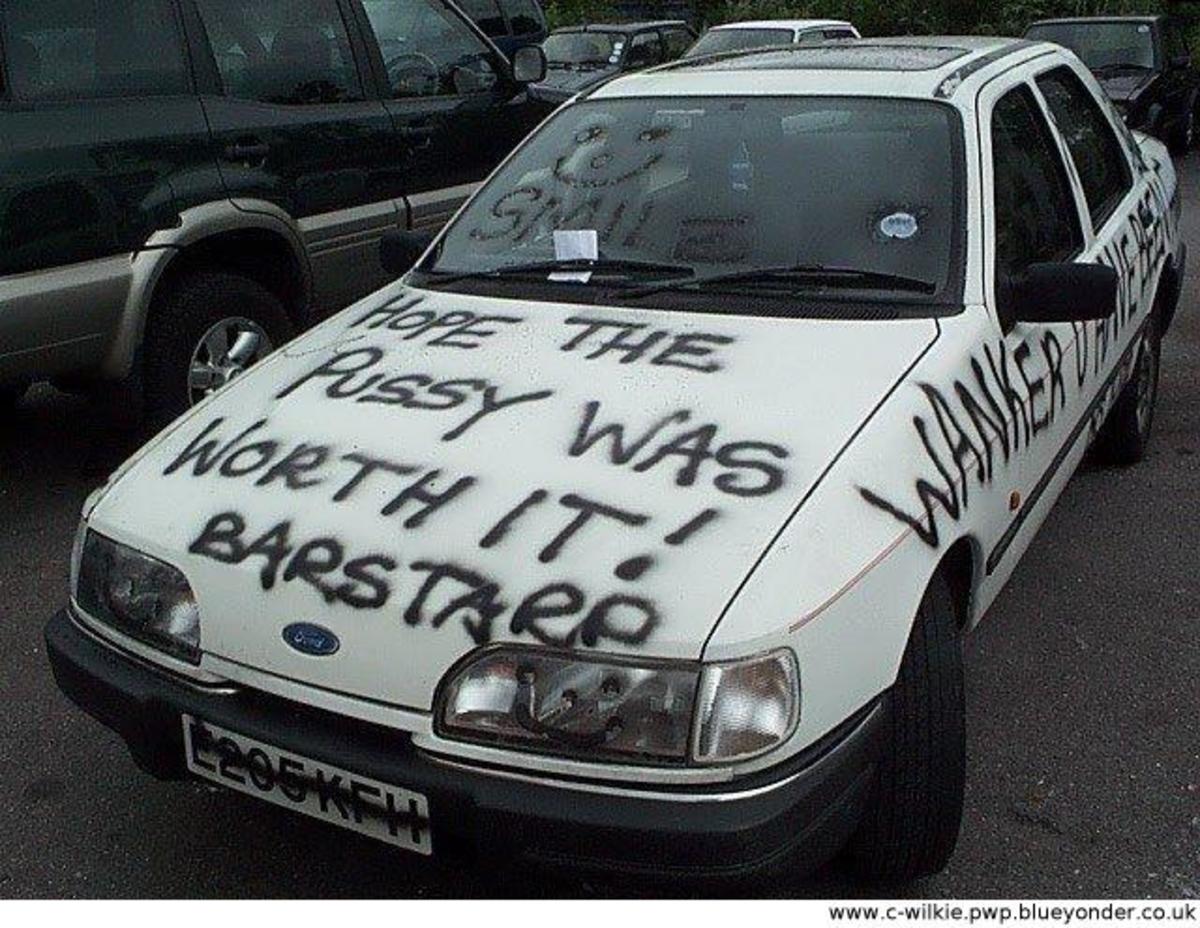

An experiment was run in the Netherlands at the University of Groningen to see if the presence of litter and graffiti had any effect on petty crime or antisocial bevaviour. Several locations were set up in one of two ways: Locations in one condition were kept in good repair; the litter was cleaned up, graffiti was removed, and broken windows were repaired. Locations in the other condition appeared unkempt and uncared for with litter, graffiti, and broken windows. Secret surveillance showed antisocial behaviour like stealing was more likely to occur in the unkempt areas.

This experiment was based on a theory about crime prevention called the 'broken windows theory'. There are three factors at its base: social norms and conformity, the presence or lack of monitoring, and social signalling and signal crime. In other words: adhering to what is socially accepted as the proper way to act; making sure others act properly, and how we act when no one is watching; and how we get clues from our physical environment that influence how we act when no one is around.

As the name nods to, broken windows on a street can lead you to some possibilities about that street. Normally, broken windows in a building would be quickly repaired because they let in rain and keep out intruders. If you encounter an area with broken windows, it may give the impression the street is uncared for either by the city or by the people living there or the area is vacant. If people are living there, you may think that the residents of the building or the street don't care about what happens to the property, perhaps the property has been neglected. If the property is neglected, one might assume it is not being monitored. Since no one is watching, the presence of one or two broken windows may encourage more to be broken, or other crimes like vandalism to occur. Small petty crimes may lead to more serious crimes if the criminals think they are not being watched and/or the people living in the area don't care what goes on there. Hence, by maintaining buildings on a street, such as replacing broken windows, incidences of petty crime would be discouraged because the residents care about the area, and it can be assumed, watch the area.

The broken windows theory was effectively used in cleaning up New York's subway system. After a subway car was cleaned of graffiti etc., it was not allowed to be put back into service if graffitied again unless it was once more reclaimed.

It has also been the subject of other experiments on crime hot spots and road crimes with positive results. Some critics say the reduction in crime in these areas came about instead by an increase in police presence and incarceration rates, as well as other diverse factors such as easier access to abortion by women with unwanted pregnancies (that have been statistically linked to higher crime rates). It is feasible these factors worked in tandem with the broken windows experimentation model to keep potential crime spots better maintained. However, the research showing the effect of the broken windows theory was not conducted only in New York. There was a positive effect on petty crime reduction in a number of other areas, such as at the University of Groningen mentioned above.

“Let everyone sweep in front of his own door, and the whole world will be clean.”

— Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.Broken Windows I Saw Around Me

In my experience, you can feel the effects of the broken window theory. The neighbourhood where I lived in Montreal had gained a bad reputation. Yet, you regularly saw both shopkeepers and residents sweeping the walks and sidewalks in front of their shops or houses. Montreal had street cleaning machines that would drive around from spring to fall and sweep the gutters. Was there still crime? Yes, but the only place I ever felt uneasy was one city block that was constantly full of litter, vandalized bus shelters, and graffiti. Was I reacting to the social signalling that crime might be more likely in these areas? I think so.

This isn't to say that crime doesn't take place in well-maintained neighbourhoods. We all know this is not true. However, according to the broken windows theory, the amount of crime in areas that are maintained would be greatly reduced.

So, what does the broken windows theory have to do with you and me? Potentially everything.

When I asked you to recall the nicest neighbourhood you knew, how did it differ from the neighbourhood with crack flophouses? Was the former more well-kept than the latter? Who kept the neighbourhood in good repair, or didn't maintain it at all? Most likely the people who lived there. People like you and me.

In Japan I saw an example of how neighbours can take control of their environment. Some neighbourhoods where I lived had quarterly neighbourhood meetings. One of the purposes of these meetings is to create a schedule for the residents to clean up the neighbourhood. On each person's appointed day, they go around the neighbourhood picking up trash. My neighbourhood was very well-kept and known as one of the nicer ones. The thing is, I lived in one of the biggest cities in Japan, so this was no small feat. For work I travelled all over Japan, so I got to see that, like everywhere, some areas were well-maintained, perhaps by a neighbourhood program, while others had lots of trash lying around.

Imagine how your neighbourhood would change if residents banded together to form a clean-up schedule? It’s also a great way to get to know each other.

If there is no neighbourhood program in place, you can always do small little actions yourself. For example, I wasn't aware of the neighbourhood programs in Japan for a long time. One day while I was taking out my trash, I decided to get rid of an old pair of gloves that had been sitting in the gutter in front of my building for a few weeks (they were hard to spot and unless you lived in our building, you’d probably not notice them). One of my neighbours came out of her door just as I was untying my garbage bag, then she stopped, jaw hitting the ground, as I gingerly picked up the very gross gloves and put them in my bag, retied it, and set the bag down for collection with the others. The neighbour, who I’d never met, came over and bowed deeply to me, a big sign of respect in Japan, and said thank you. I did it because I lived in the building and didn't like trash on the street out front. I enjoyed the cleanliness of our neighbourhood and wanted to keep it that way.

On a street I lived on in Montreal, a vandal had kicked over all the recycling bins down my very long street. I stood, looking at the overturned bins and debated whether I should spend the time to pick them all up when I had a pressing contract to finish at home. What made me spend the next hour picking up other people’s trash was knowing that a lot of school kids walked down my street. It was a decent street and easy to see people took care of their properties. So I spent that precious time cleaning in the hopes of setting a good example as well as to avoid having a 'broken window' of overturned garbage cans.

“The test of a civilization is the way that it cares for its helpless members.”

— Pearl BuckBroken Windows Go Beyond The Physical

The broken window theory also applies to our behaviour in how we react or fail to react. If someone is making fun of someone else, even just making a joke at the expense of some other cultural group, do we laugh along - when we’d be upset if someone did that to us - or not say anything at all, thereby giving silent consent to the behaviour? It’s not necessarily easy to say the behaviour is unacceptable, but if we help one person by doing the right thing, it’s worth a bit of discomfort, isn’t it?

This kind of behavioural broken window goes beyond just ourselves, of course, and applies to our family, friends, neighbours, colleagues, and all the way up to large organisations, cities, and governments.

'Broken windows' can also appear in the form of the language we use, our actions, and the opinions we hold. For example, I've started questioning if cursing is ever good. There are much more constructive ways to deal with anger and frustration, or seek social status, than through cursing. For another example, if we choose to continue buying unsustainably sourced, and/or heavily processed, and/or over-packaged products, we are telling companies to keep producing them. And if we hold and express beliefs that are discriminatory in any way, such as "Oh, well that happens in those kinds of families (or between those kinds of people)" , then we are condoning discrimination as an okay practice, which may tip forward like the first grains of snow of an avalanche and lead to more severe forms like racism and prejudice. Sure this doesn’t necessarily happen overnight, but neither does a garden full of weeds.

Is It Worth It?

It is always within our reach to fix broken windows in our neighbourhoods and within ourselves. Whether it leads to a major reduction in petty crime or a minor reduction in more serious crime, it is worth the effort because that is one less crime committed and one victim that has been spared the pain of the experience. Within ourselves, every broken window we fix, whether it is monitoring our speech or making more informed consumer choices, it is one more change for the better. Wouldn't you want someone to do that for you?

Please tell us below other examples or ways you have fixed broken windows in your life.

This content is accurate and true to the best of the author’s knowledge and is not meant to substitute for formal and individualized advice from a qualified professional.

© 2019 Amanda Hare